The first public statement of The Ripon Society was written in the weeks following the assassination of President John F. Kennedy. It was distributed to Republican leaders on January 6, 1964, as a new session of Congress convened and as the 1964 Presidential campaign officially began. Drafted by the founding members of The Ripon Society, the statement is as follows:

“A Call to Excellence in Leadership”

An open letter to the new generation of Republicans January 6, 1964

For a moment, a great Republic stood still.

Everywhere, men reacted first in disbelief and horror, then in anger and shame, and then in more measured thought and silence. The President is dead. A nation is in mourning.

History provides us with few such occasions to pause and reflect upon the state of our society and the course of its politics. While we yet sorrow, so must we seize this moment before our thoughts slip away to be lost in the noise of “life as usual.”

It is in this context that we have chosen to speak. We speak as a group of young Republicans to that generation which must bear the responsibility for guiding our party and our country over the coming decades. We speak for a point of view in the Republican Party that has too long been silent.

The Republican Party today faces not only an election but a decision. Shall it become an effective instrument to lead this nation in the last third of the twentieth century? Shall it emerge from the current flux of American politics as the new majority party? Or shall it leave the government of the nation to a party born in the 1930’s which appears unable to meet the challenge of a radically new environment?

We should like to approach this decision from three aspects – the strategy for achieving a new Republican consensus, the nature of a Republican philosophy appropriate to our times, and the qualities of excellence required in our leadership.

TOWARD A NEW REPUBLICAN CONSENSUS

Recent election results indicate that there is no clear political consensus in the country. We are perhaps at one of those points in our political history when new majority is about to emerge.

American politics has been by and large one-party politics. A single party has been dominant for considerable periods of our past history – the party of Thomas Jefferson, the party of Abraham Lincoln, and most recently the party of Franklin Roosevelt. Each of these great parties emerged during a period of revolution in political ideas and was based upon a new majority consensus.

“The President is dead. A nation is in mourning. History provides us with few such occasions to pause and reflect upon the state of our society and the course of its politics. While we yet sorrow, so must we seize this moment before our thoughts slip away to be lost in the noise of “life as usual.”

The Roosevelt coalition of the 1930’s is still the majority party in this country. But its loyalties are fading, its base is eroding, and its dynamism has been exhausted. FDR forged his great coalition of the urban minorities, trade unions, “liberal” intellectuals, farmers, and the Democratic South with a program to meet the economic distress of the depression years. Accordingly, the Democratic party of today looks back to 1932 and 1936 and has never quite been able to escape the dialogue of domestic politics from that period. In a real sense, the Democratic coalition of the 1930’s, dedicated to the preservation of its economic and social gains since the Great Depression has become the “stand-pat” party of today.

At the time of his death, John F. Kennedy was attempting to rebuild the Roosevelt coalition — to infuse it with the idealism of a new generation that found the political issues of the depression years increasingly irrelevant. He was seeking to lift the Democratic party to a broader international concern. But fate deprived him of that opportunity — and fate also delivered control of his party to — a leader far closer to the era of Roosevelt than to his own. Lyndon Johnson tried to put Roosevelt’s coalition back together once again. Trained as an apprentice of the New Deal; representing the Southern wing of his party with its decidedly regional orientation; inclined by temperament to national rather than international concerns; will he not be a “prisoner of the past?” While the nation may admire his knowledge of political power and his ability to manipulate it, Lyndon Johnson is not likely to fire the hearts and minds of Americans. At best, his will be an administration of “continuity.” And so will any Democratic administration which does not take cognizance of the radically transformed nature of American politics.

If the Democratic party, bound to the clichés and fears of past history, is incapable of providing the forward-looking leadership this country needs, the Republican party must. There are at least two courses open to the party — the strategy of the right and the strategy of the center. We feel strongly that the center strategy is the only responsible choice the party can take. The strategy of the right is a strategy for consolidating a minority position. It is an effort to build a coalition of all who are opposed to something. As an “anti-” movement, it has been singularly devoid of positive programs for political action. The size and enthusiasm of the conservative movement should not be discounted, however. It represents a major discontent with the current state of our politics, and, properly channeled, it could serve as a powerful constructive force. But the fact remains that the strategy of the right, based as it is on a platform of negativism, can provide neither the Republican party with an effective majority nor the American people with responsible leadership. The strategy of the right should be rejected for another basic reason. It is potentially divisive. Just as Disraeli warned the British Conservative party a century ago of the dangers of the “two Englands,” so would we speak out against a party realignment of the small states of the West and South against the urban centers of America — or any similar realignment that would pit American against American on the basis of distrust or suspicion. We must purge our politics of that rancor, violence, and extremism that would divide us. In the spirit of Lincoln, we must emphasize those goals and ideals which we hold in common as a people:

“With malice toward none; with charity for all; with firmness in the right, as God gives us to see the right, let us strive to finish the work we are in; to bind up the nation’s wounds; . . . — to do all which may achieve and cherish a just and lasting peace among ourselves, and with all nations.”

We believe that the future of our party lies not in extremism, but in moderation. The moderate course offers the Republican party the best chance to build a durable majority position in American politics. This is the direction the party must take if it is to win the confidence of the “new Americans” who are not at home in the politics of another generation: the new middle classes of the suburbs of the North and West — who have left the Democratic cities but have not yet found a home in the Republican party; the young college graduates and professional men and women of our great university centers — more concerned with “opportunity” than “security;” the moderates of the new South – who represent the hope for peaceful racial adjustment and who are insulted by a racist appeal more fitting another generation. These and others like them hold the key to the future of our politics.

Since 1960 John F. Kennedy had moved to preempt the political center. Republican moderates for the most part remained silent. Now the very transfer of power means that the center is once again contestable. We believe that the Republican party should accept the challenge to fight for the middle ground of American politics. The party that will not acknowledge this political fact of life and courageously enter the contest for power does not merit and cannot possibly win the majority support of the American people.

“As Republicans, we must prove to the American people that our party, unbeholden to the hostages of a faded past, is a more flexible instrument for the governing of this great nation and for the realization of dignity at home and around the world.”

Must the Republican party then adopt Kennedy-New Frontier programs to compete for the center? No. Such a course would be wrong and it would smack so obviously of “political opportunism” as to insure its defeat. The Republican appeal should be rooted in the party’s own rich history and current strengths. As Republicans, we must prove to the American people that our party, unbeholden to the hostages of a faded past, is a more flexible instrument for the governing of this great nation and for the realization of dignity at home and around the world.

TOWARD A MATURE REPUBLICAN PHILOSOPHY

A Republican philosophy capable of capturing the imagination of the American people must have at least three attributes. It must be oriented toward the solution of the major problems of our era – it must be “pragmatic” in emphasis. It must also be “moderate” in its methods – concerned more with the complexities of the means toward a solution than with a simplistic view of the ends. And finally, it must marry these attributes of pragmatism and moderation with a passion to get on with the tasks at hand.

* * * * *

First, our philosophy must be oriented toward the solution of problems. The image of “negativism” that has too frequently been attached to our party must be dispelled. The new generation in American politics is looking for a party that is able to grasp the problems of the last third of the twentieth century and able to devise meaningful solutions to them. We note only the most salient: the legitimate aspirations of the Negro in the northern cities, as well as in the South; the human adjustments to the process of automation in industry and in business; the phenomenon of the megalopolis with the attendant problems in housing, transportation and community services; the emphasis of quality in our educational system, our health services, and our cultural services in general.

The Democratic party will have solutions or purported solutions to all these domestic problems. But does it have the imagination demanded by the new world we face? Or will its answers merely be retreads of the “New Deal,” more of the same, more indiscriminate massive federal spending, more government participation in the economic and social life of the nation and of the individual?

A CALL TO EXCELLENCE

If our times demand new vision and new solutions on the domestic scene, how much greater is the need on the international front. The greatest challenge this nation will face in 1970, 1975 and 1980 will most likely be decisions in its foreign policy. Merely “to continue” our foreign policy will not be enough. The American President must now serve as “the first statesman of the world.” He must set new directions in foreign policy, shape new relationships with Europe, pioneer new means of weapon control, understand the diffusion of power within the Communist bloc. All of this will demand the finest qualities of statesmanship, of political engineering, of shrewd bargaining and adjustment of which our nation is capable. The Republican party has produced a proud lineage of pragmatic statesmen since Lincoln. It is our hope that once again it will provide the leadership to meet the occasion.

* * * * *

While our philosophy and our program must be pragmatic so must it be moderate. Simply to define the problems is not to solve them. The moderate recognizes that there are a variety of means available to him, bur that there are no simple unambiguous ends. He recognizes hundreds of desirable social goals where the extremist may see only a few. Moreover, the moderate realizes that ends not only compete with one another, but that they are inextricably related to the means adopted for their pursuit. The moderate chooses the center — the middle road — nor because it is halfway between left and right. He is more than a non-extremist. He takes this course since it offers him the greatest possibility for constructive achievement.

The image of “negativism” that has too frequently been attached to our party must be dispelled.

In contrast, the extremist rejects the complexity of the moderate’s world. His is a state of mind that insists on dividing reality into two antithetical halves. The gray is resolved into black and white. Men are either good or evil. Policies are either Communist or anti-Communist. It is understandable that the incredible complexity and mounting frustrations of our world will cause men to seek one right answer – the simple solution. The moderate cries out that such solutions do not exist, but his would appear to be a thankless task. Who will reward him for telling them their dreams can never be? It is not surprising that the doctrinaire has always reserved his greatest scorn for the pragmatist and not for his opposite number. The moderate poses the greatest danger to the extremist because he holds the truth that there is no simple “truth” that will answer all his questions with ease.

Moderation is not a full-blown philosophy proclaiming the answers to all our problems. It is, rather, a point of view, a plea for political sophistication, for a certain skepticism to total solutions. The moderate has the audacity to be adaptable. The Republican moderate approaches these problems from a more conservative perspective, and the Democratic moderate – from a more liberal one. The fact that we may meet on common ground is not “me-tooism.” It is time to put away the tired old notion that to be “real Republicans” we must be as different as possible from our opponents! There is no more sense in that view than in the idea that we must be for isolationism, prohibition, or free love because our opponents are not. It is time we examined the merits of a solution in itself rather than set our policy simply in terms of the position the Democratic party may have taken.

* * * * *

But can the moderate produce the image of conviction and dedication that has been so much a part of the attraction of extremists throughout history? Is the “flaming moderate” just a joke, or is he a viable political actor? Can we be emotional about a politics so pluralistic, so relative, so limited in its range of available maneuver? Perhaps we share the too abundant enthusiasm of youth but we feel that we not only can – we must. We must show our world that our emotions can be aroused by a purpose more noble and a challenge more universal than the cries of irresponsible extremism. Tempered with an honest uncertainty we must be ever willing to enter upon yet another great crusade. We must learn to be as excited about open-mindedness as we once were about final answers, and as dedicated to partial solutions as we have been to panaceas. We must engage life as we find it, boldly and courageously, with the conviction that if we and reason endure we shall surely succeed — and with the knowledge that the greatest sin is not to have fought at all.

TOWARD EXCELLENCE IN REPUBLICAN LEADERSHIP

The Republican party must not only define a new strategy and a positive program but it must also find the men who can forge a new national party; men who can renew the great progressive Republican tradition; men who possess the qualities of excellence that we should be the first to see as “the Kennedy legacy.”

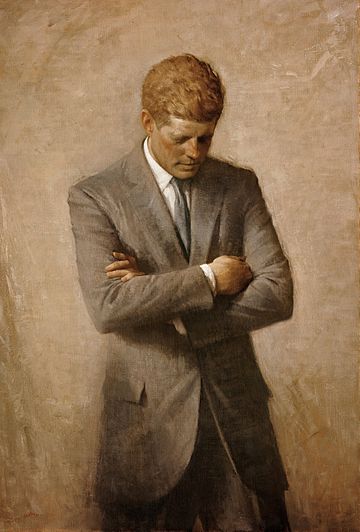

As Republicans, we have often disagreed with programs of the New Frontier. As members of the responsible opposition, we have been critical of the Kennedy administration’s performance. But as Americans and as members of a generation still younger than his, there was something in John F. Kennedy that we admired. It would be petty to ignore this, and dishonest to deny that we look for no lesser qualities in the future leadership of our own party.

John F. Kennedy brought to the Presidency a perspective of the years ahead. His vision of America and its role in the world was not simply the product of youth, of the “new generation of Americans” to whom the torch had been passed. It was derived from those qualities of mind and spirit that comprise his legacy to us: his sense of imagination and inquisitiveness, his subtle and keen intelligence, his awareness of the ultimate judgment of history, his courage to affirm life, his love for the art of politics, his respect for excellence. Robert Frost had spoken of his era as an “age of poetry and power.” Kennedy brought to the Presidency a style and a zest that challenged the idealism and won the enthusiasm of our generation.

Republicans protested with candor that there was too much style and not enough substance to his policies. Fate denied us a full judgment on that question. The merits of the man and his leadership will long be debated, but there are lessons in his life and death that we cannot completely escape. We have witnessed a change in the mood of American politics. After Kennedy, there can be no turning back to the old conceptions of America. There can be no turning away from the expectations of greatness that he succeeded in imparting.

To all thinking Republicans, the meaning of November 22nd, 1963, should be clear. The Republican party now has a challenge to seek in its future leadership those qualities of vision, intellectual force, humaneness and courage that Americans saw and admired in John F. Kennedy, not in a specious effort to fall heir to his mantle, but because our times demand no lesser greatness.

Our party should make the call to excellence in leadership virtually the center of its campaign platform for 1964 and for the years to come. The Republican party should call America’s finest young leaders into the political arena. It should advance its talented younger leadership now to positions of responsibility within the national Republican party and the Congress. Great government requires great men in government. In a complex age, when truth is relative and total solutions elusive we can do no more than pledge the very best qualities of mind and soul to the endless battle for human dignity. And we dare do no less at every level of social activity, from the presidency to the town selectman.

The moderates of the Republican party have too long been silent. None of us can shirk the responsibility for our past lethargy. All of us must now respond to the need for forceful leadership. The moderate progressive elements of the Republican party must strive to change the tone and the content of American political debate. The continued silence of those who should now seek to lead disserves our party and nation alike.

The question has often been asked, “Where does one find’ ‘fiery moderates’?” Recent events show only too clearly how much we need such men. If we cannot find them, let us become them.