There have been more than 15 attempts to reform and reorganize the United States federal government since the Progressive Era in the early 1900s.

The latest of these efforts – led by President Trump and Elon Musk and branded the Department of Government Efficiency, or DOGE – is literally shaking the foundation of official Washington with its no-holds-barred approach.

With Congress taking a backseat as federal workers are offered buyouts and federal agencies like USAID are shut down, and with many legal scholars arguing that these and other actions taken by DOGE are unconstitutional, now is a good time to not only look back on some of these prior reform efforts, but ask whether the lessons of the past are even relevant today.

The First Hoover Commission (1947-1949)

An efficiency-conscious Republican Congress adopted the Lodge-Brown Act in July 1947 to “straighten out” the federal government. Formally, this law created a Commission on the Organization of the Executive Branch of the Government, but it quickly became more widely known as the Hoover Commission after its chair, former President Herbert Hoover.

The first Hoover Commission was envisioned to lay the groundwork for a Republican president since President Harry Truman was at the time widely viewed as unpopular and likely to not be elected in 1948. The Commission’s report was to be delivered after the 1948 election. But Truman won.

The recommendations of the first Hoover Commission led to the creation of the Executive Office of the President, the General Services Administration, the National Science Foundation, and the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare.

Still, Truman embraced the final report and its recommendations, which had been developed by a bipartisan, 12-member commission that included Members of Congress. This Commission has been popularly seen as the highwater mark in American government reform. Why?

The Commission focused its attention on “improving programs” and better performance of government. For example, it recommended a major reorganization of functions to significantly reduce the number of agencies reporting directly to the president. Its recommendations led to the creation of the Executive Office of the President, the General Services Administration, the National Science Foundation, and the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare.

When the Commission was created, both the House and Senate were controlled by Republicans. But by the time the Commission’s report was released 18 months later and implementation got underway, all three branches were controlled by Democrats. That may have eased the adoption of many of the recommendations. The value of a congressionally chartered Commission, with a bipartisan membership appointed by the President, House and Senate leaders likely added legitimacy and acceptance to the effort.

The Second Hoover Commission (1953-1955)

When Dwight Eisenhower took office in 1953, both houses of Congress were under the control of Republicans. Congress created a second statutory Commission with largely the same mandate as the first. Yet, this second Commission was largely seen as less successful.

Former President Hoover also chaired this effort, but there was a new focus – “eliminating programs.” There were proposals to eliminate “government competition with private enterprises” and either privatize activities or end programs by contracting them out to the private sector to perform. The final report was released 22 months later. It detailed 2,500 commercial-type government activities seen as competitive with the private sector. There were also proposals to terminate some programs by devolving them to state and local governments, such as urban renewal programs.

However, by the time the Commission’s report was released in 1955, both houses of Congress fell under the control of Democrats. There was opposition to eliminating programs and activities. There was support, however, for recommendations to improve programs such as the Commission’s budget and accounting reforms, and the reduction of reporting and survey burdens on the public.

The Grace Commission (1982-1984)

In the second year of Ronald Reagan’s presidency, he chartered a “private sector review of the operations of the Federal Government to identify opportunities for efficiency and cost reduction.” This review – officially known as the President’s Private Sector Survey on Cost Control – was led by corporate executive J. Peter Grace who recruited a cadre of 161 corporate chief executives who loaned the Commission some 2,000 staff to conduct dozens of reviews. The effort was staffed and funded entirely outside the government, and took 18 months to complete. Its focus was on “eliminating programs.”

According to the Congressional Research Service (CRS), the final effort produced 47 volumes (23,000 pages) with 2,478 specific recommendations. The Commission recommended privatizing certain functions such as federal power marketing, reducing the federal workforce via attrition, and means-testing certain benefits such as veterans disability payments.

In the second year of Ronald Reagan’s presidency, he chartered a “private sector review of the operations of the Federal Government to identify opportunities for efficiency and cost reduction.”

The Commission claimed that if its recommendations were adopted, savings would total $424 billion in the first three years. The savings claims were seen as highly inflated and many were controversial.

President Reagan accepted 83 percent of the Commission’s recommendations. Of these, a large number of recommendations to improve programs were adopted but CRS noted: “Savings in administrative expenses directly attributable to the Grace Commission were modest.” These included, for example, the adoption of electronic funds transfers and other commercial financial practices. They also laid the groundwork for the eventual adoption of the Chief Financial Officers Act of 1990.

Reinventing Government (1993 – 2001)

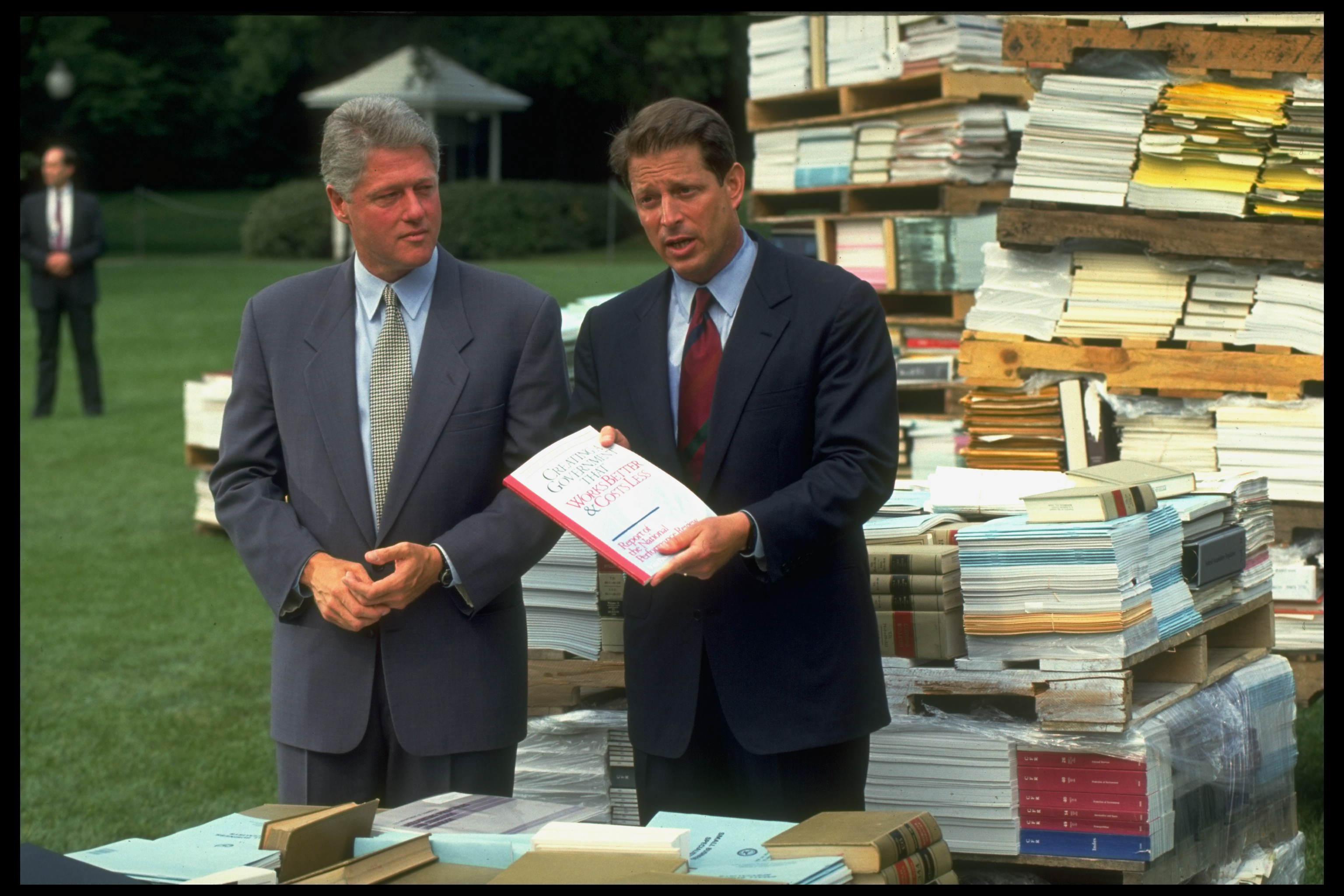

Just weeks into his administration, President Bill Clinton launched the National Performance Review (NPR), also dubbed “Reinventing Government.” He placed Vice President Al Gore at its head, who in turn recruited a temporary task force of about 250 career civil servants. Vice President Gore counseled the leaders of the Review to “don’t move boxes; fix what’s inside them” – the “improving programs” route. As a consequence, it focused on reducing mission support costs, largely through staff reductions, and modernizing operations through technology and “cutting red tape.” The initial report was released six months later.

Subsequent implementation was promoted by a small task force of career managers reporting to Vice President Gore over the following eight years. Two-thirds of its recommendations were adopted, resulting in $136 billion in savings and a workforce reduction of 426,200.

Two-thirds of the recommendations of the Reinventing Government Task Force led by Al Gore were adopted, resulting in $136 billion in savings and a workforce reduction of 426,200.

While most of its recommendations could be achieved administratively, NPR achieved a number of legislative successes to improve program operations. These included adopting measures of government performance; streamlining purchasing (for example, by adopting the use of purchase cards); and modernizing the government’s approach to technology (for example, by requiring agencies to appoint chief information officers and giving them authority over computer purchases). However, because many of its initiatives were administratively based, they lacked sustainability over time, especially those related to employee empowerment initiatives and recognition.

Lessons from the Past

In looking back at past reform efforts, there are some useful lessons.

First, a focus on making government work better can gain significant support, as was seen in the first Hoover Commission and the Reinventing Government initiatives. There are signs that DOGE will devote some efforts to “improving performance” through its embrace of information technology initiatives.

Second, when recommendations need congressional approval, being fast can make a difference. When a reform initiative spans the life of more than one Congress – and there is a chance that either house may flip to the opposing party – then bolder recommendations can be jeopardized. Moving fast also allows more time to focus on implementation. This was a strength of the Reinventing Government initiative.

There is evidence that including career civil servants in the work of a reform initiative can increase the success of the “improving program” initiatives since they can gain “buy-in” from the civil service.

And third, reform efforts that try to make government cheaper, such as by eliminating programs or reducing headcount, necessarily involve Congress. Such an emphasis was a stumbling block for the Second Hoover Commission and the Grace Commission. As DOGE launches its initiatives, it will be important for the team to work with Congress as they move along the “eliminating programs” path which will require congressional action. DOGE now has the luxury of both houses of Congress being held by the Republicans. If congressional actions are not completed by the end of 2026, there is the possibility of a Democratically controlled House or Senate. As seen in previous initiatives, a change in Congress can significantly affect the chances of legislative approval.

Finally, there is evidence that including career civil servants in the work of a reform initiative can increase the success of the “improving program” initiatives since they can gain “buy-in” from the civil service. In contrast, the “eliminating programs” approach has been predominately staffed by individuals outside of government, and civil service “buy-in” was not sought.

Are These Lessons Even Relevant Today?

At the time of this writing, DOGE has not been operating like any of these past reform efforts, where the need for change is assessed, and recommendations are made for the President and Congress to act upon.

By contrast, DOGE and Musk have been acting unilaterally with little regard for past precedent and even less regard for congressional authority and control. Besides offering buyouts to federal employees and closing down USAID as previously mentioned, DOGE operatives have gained access to the personnel payment systems and databases at the Office of Personal Management.

This approach is not only unorthodox, but it also may be – again, as previously mentioned – unconstitutional. As such, the relevance of previous reform initiatives – while interesting and instructional and informative — is also profoundly unclear.

In short, America is in uncharted territory when it comes to government reform, with President Trump and Elon Musk setting the direction, and Congress, the Courts, and the American people along for the ride.

John M. Kamensky is Emeritus Senior Fellow, IBM Center for The Business of Government. His email: john.m.kamensky@gmail.com. Mark A. Abramson is President, Leadership Inc. His email: mark.abramson@comcast.net.