The administration of Joseph R. Biden has enacted a record-setting number of consequential regulations this spring, according to an analysis by George Washington University. In April alone, 66 “significant” final rules were finalized — meaning they “have an annual effect on the economy of $100 million or more or adversely affect in a material way the economy, a sector of the economy, productivity, competition, jobs, the environment, public health or safety, or State, local, or tribal governments or communities.”

All told, Mr. Biden’s administration has issued nearly 250 significant rules since taking office in 2021, a pace that far exceeds any previous president. Big rules are not the only rules being produced by Mr. Biden’s executive branch. The same report tallies an average of 262 rules per month during the President’s term.

Regulations have the effect of law, and the Biden administration has used them to impose policies on major issues that are important to the Democratic party. Recent rules, for example, goad automakers to produce more electrical vehicles, forgive student loans for some borrowers, and reclassify many independent contractors as employees entitled to overtime pay and other federally stipulated benefits and protections.

All told, Mr. Biden’s administration has issued nearly 250 significant rules since taking office in 2021, a pace that far exceeds any previous president.

Whatever one thinks of these policies, making them through regulations circumvents Congress. Indeed, presidents often unabashedly enact regulations contrary to the express will of Congress. Consider Mr. Biden’s efforts to cancel the loans of former college students or Barack H. Obama’s curbs on natural gas “fracking,” both of which were adopted despite the opposition of a GOP-controlled House. To be sure, Republican presidents do the same. Donald J. Trump, for example, sought to alter migrant asylum policies despite the howls of the Democrats holding the lower chamber. In each of these instances, the president could not get a statute through both chambers and chose to impose their policies through rulemaking.

Mostly, legislators respond to regulations they dislike by issuing press releases, tweeting, and generally making noise. They also introduce Congressional Review Act (CRA) resolutions, a fast-track process that enables majorities in both chambers to rapidly strike down a pending rule. The current Congress has responded to Mr. Biden’s regulatory blitz with a record 109 resolutions. Rarely do CRA resolutions succeed. To take effect, either a president must sign them, Congress must pass them over his veto, or it must time the passage of a resolution so that it lands when a new, more congenial president takes office.

All too frequently, Congress relies on the courts to protect its legislative authority. This sometimes works; the Supreme Court and federal benches struck down Biden’s initial student loan forgiveness policy, Trump’s asylum rule, and Obama’s fracking restriction. But it is a crapshoot, and there is little to stop a determined president from continuing to try to use regulatory authority to get what he wants. President Biden, for example, has moved forward with student loan cancellation and declared, “I will never stop working to cancel student debt – no matter how many times Republican elected officials try to stop us.”

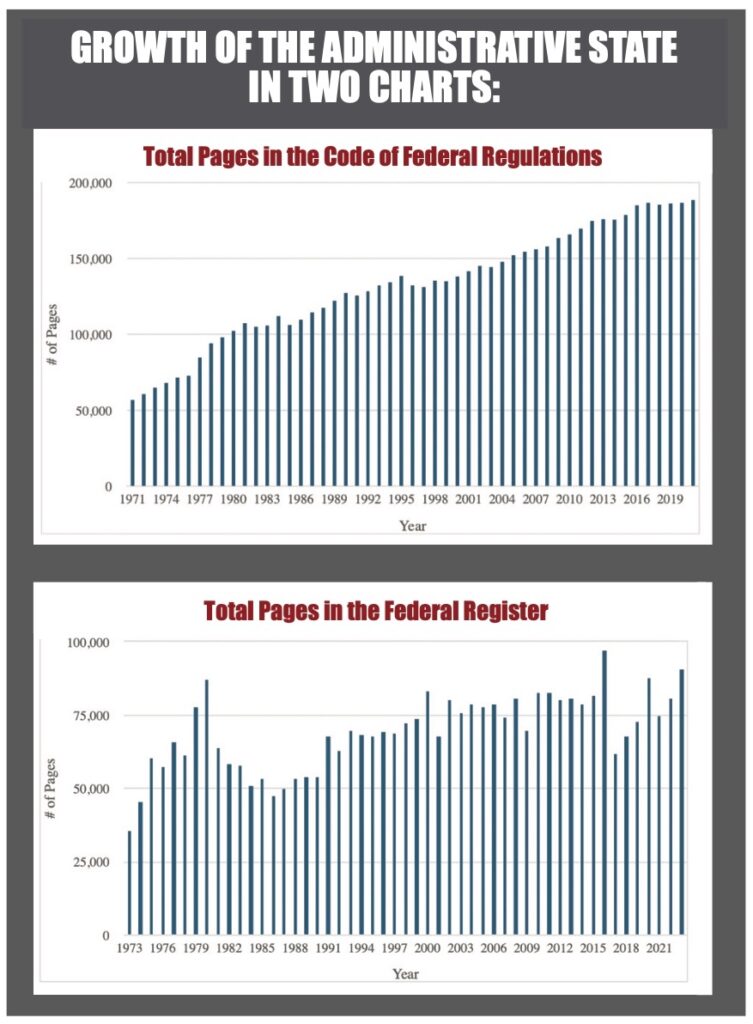

But only the biggest regulations end up in the courts, which means that usually the executive branch gets what it wants. Despite the U.S. Constitution’s insistence that “All legislative Powers herein granted shall be vested in a Congress of the United States,” the presidency is making a lot of policy. There are now 186,000 pages of federal regulations, more than triple the quantity in the mid-1970s, which is to say nothing of the innumerable agency guidance and explanatory documents (“regulatory dark matter”) that also specify how policy works.

Congress can give itself the power to forcefully engage in regulatory policy by establishing a Congressional Regulation Office inside the legislative branch.

Sure, the public can participate in “public comment” during the rulemaking process, but few do, and even those who do likely will find their comments brushed off by agencies bent on doing what they think best. The growth of the administrative states has made for a hollowing out of representative government.

It does not have to be this way. Congress can regain its fumbled-away legislative authority. Certainly, a direct means to that end would be to reduce the size of the federal government, which has perhaps 180 executive and independent agencies producing rules. But cutting government is difficult, and even if it were successful Congress would remain largely hapless in dealing with the regulation issued by the remaining agencies.

Why? Because regulation is really complex and Congress has no staff dedicated to helping it oversee it. Consider, for example, the elected official who sees the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services’ proposed rule to modify the “Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act National Council for Prescription Drug Programs Retail Pharmacy Standards.” The policy is 27 pages long and chock-full of technical terms and inscrutable policy lacunae and has a price tag of $386.3 million. Said legislator and his staff have a snowball’s chance in Hades at understanding it to say nothing of improving it.

My American Enterprise Institute colleague, Philip Wallach, and I have argued that Congress can give itself the power to forcefully engage in regulatory policy by establishing a Congressional Regulation Office (CRO) inside the legislative branch. Staffed by perhaps a couple hundred nonpartisan experts, the CRO would perform benefit-cost analyses of agencies’ significant rules in order to provide a disinterested check on agencies’ self-interested math. These CRO scores should be posted online, submitted as public comments, and delivered to Congress’s committees.

The CRO also should deliver reports assessing the efficacy of existing regulations and provide advice for fixing or deleting those that are bad, anachronistic, or needlessly expensive. All of which would help Congress better write laws that better direct the executive branch’s implementation.

Congress would need to spend perhaps $50 to $75 million per year to run a Congressional Regulation Office. GOP legislators might flinch at the idea of spending more public funds on Congress, but that would be pennywise and pound-foolish. The CRO would be a net benefit to the nation if it helped Congress reduce the cost of just a few of the major regulations each year.

Kevin R. Kosar is a senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute and the editor of UnderstandingCongress.org.