During the past few years, the question of whether social media use explains rising mental health problems among American youth has exploded into public consciousness. Aside from numerous laws restricting youth access to such programs, the U.S. Surgeon General has proposed adding cigarette-style warning labels to social media apps. But is there any evidence such warning labels would be useful?

Data on Youth Mental Health

The best means of tracking mental health trends is with suicide data. This is because suicide data are less subject to confounds and unreliability common in other data such as self-report. For instance, it is sometimes reported that teen self-injuries have risen over time, although new data suggests that this was due to a change in reporting standards rather than an actual trend.

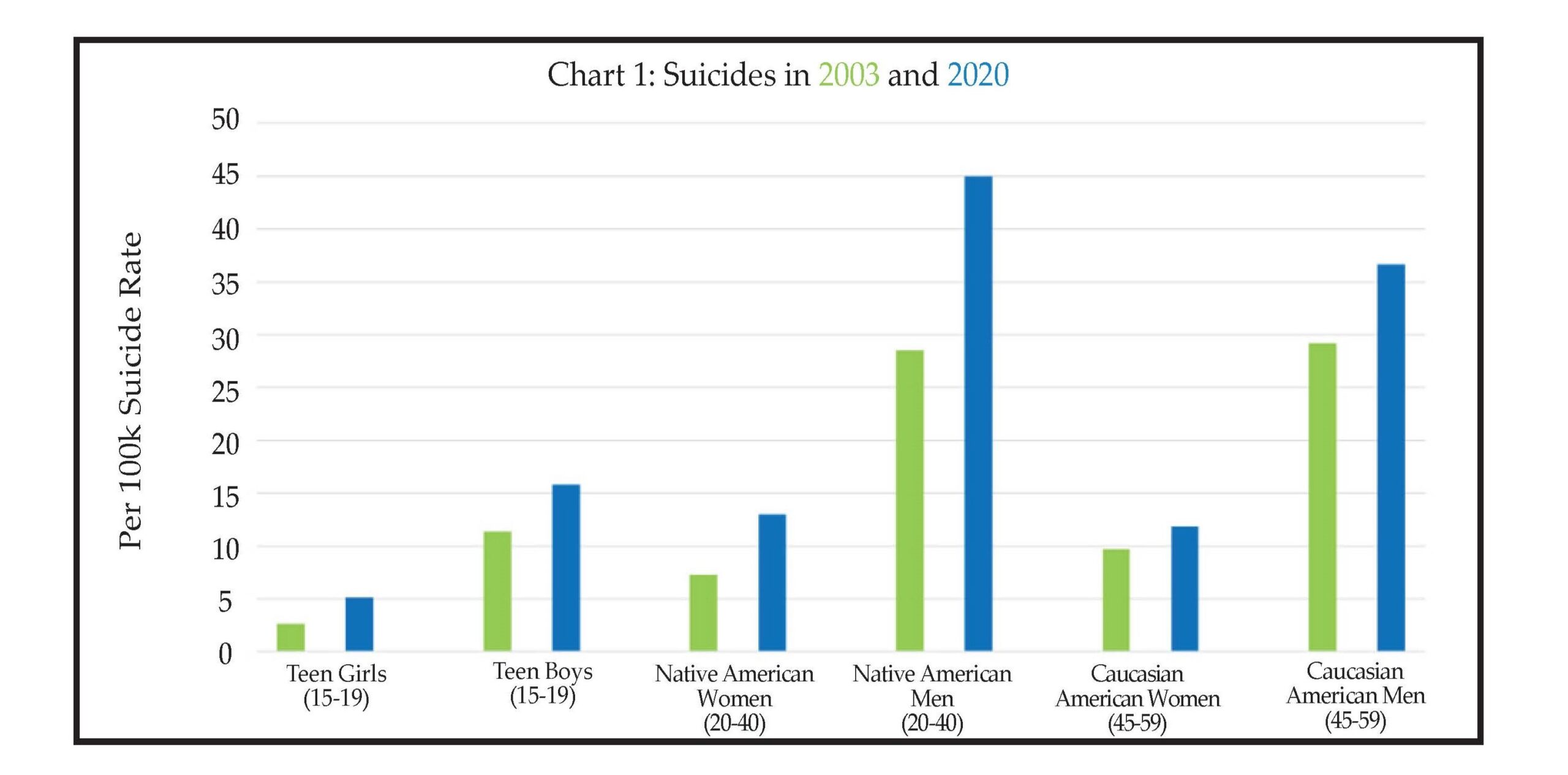

Regarding suicide data provided by the Centers for Disease Control (CDC), we quickly see that a hyperfocus on teens, particularly teen girls, has obscured a larger picture for the United States. Suicides among teen girls have, indeed, risen over the last decade in the United States. Yet, they remain one of the least suicide committing groups. By contrast, suicides among either middle-aged men or young Native American men are about 3-5x more frequent and their absolute increase has been much greater. The graph below documents the rise in suicide across several groups from 2003 to 2020 using CDC data (Chart 1).

This suggests that the U.S.’ problem with suicide is not a teen thing. Indeed, the obvious conclusion is that some teens are experiencing mental health problems because their parents are also experiencing mental health problems. Researcher Mike Males has documented this with other CDC data. In this data, teen suicidal ideation is related to parental emotional and physical abuse, not social media use. Fortunately, this past year youth suicides declined without any social media regulation, but this wasn’t true for older adults.

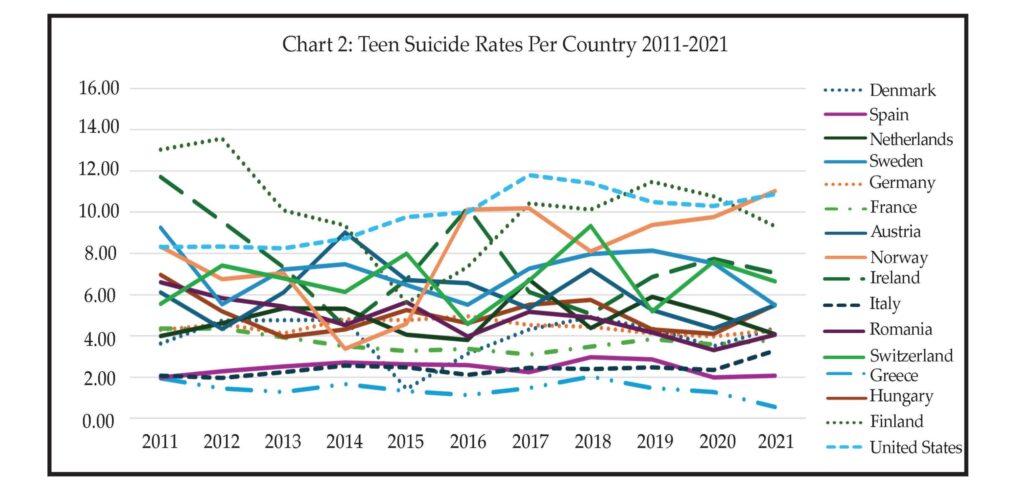

If the explanation for teen suicide and mental health problems was social media, we’d expect to see similar problems in other countries with high technology adoption. However, we simply do not. For instance, across European countries, teen suicides fell slightly during the same period in which U.S. suicides rose (Chart 2).

If the explanation for teen suicide and mental health problems was social media, we’d expect to see similar problems in other countries with high technology adoption.

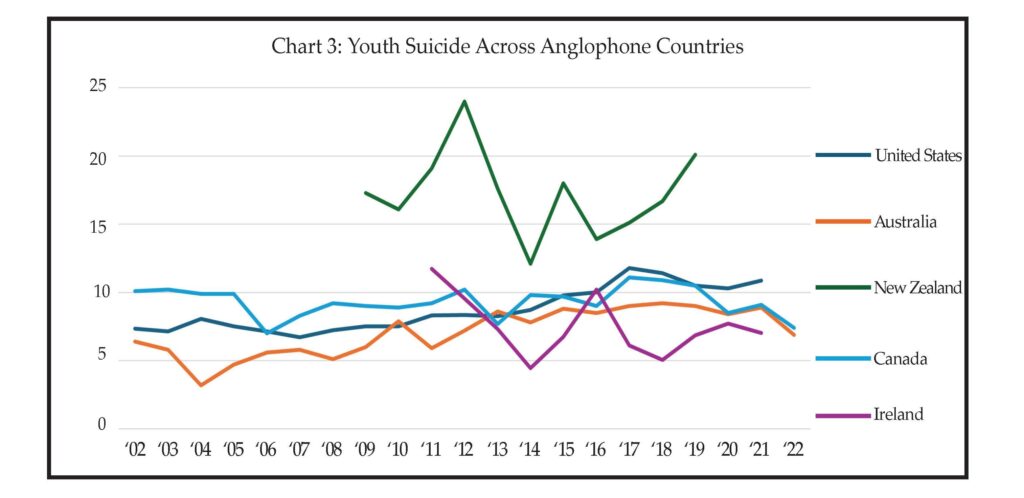

Nor do we see any pattern in teen suicides across Anglophone countries (Chart 3).

Put simply, the U.S.’ problem with mental health is unique to the U.S. To the extent that teens are involved, the clearest explanation is that this is mainly a trickle-down effect from parents’ mental health problems. If we’re serious about youth mental health, we should start treating it as a family issue, not with useless warning labels on technology.

If we’re serious about youth mental health, we should start treating it as a family issue, not with useless warning labels on technology.

Data From Research Studies

As often happens when people worry about new technology (e.g., video games, television, the radio, comic books, rock music), we hear about some mythical body of scientific evidence pointing toward harmful causal effects. However, just as with these previous eras, it turns out that no such body of scientific evidence exists.

There are, indeed, many studies of social media effects, but many are of low quality and, as a group, they do not point toward clear evidence for harmful effects.

Most experiments of social media harms ask young adults (few involve teens) to restrict their social media use for a week or more, then see if they are happier. These studies have a pretty straightforward problem in that the hypotheses of these studies are pretty obvious. This can cause people to behave how they think the researchers want them to. Nonetheless, in a recent meta-analysis of these studies I conducted, across studies they provided no evidence for causal effects. Reducing social media time does not improve mental health.

What about correlation? Is there at least a predictive relationship between social media use and teen mental health? Once again, the answer is no. In several recent meta-analyses, the correlation between social media use and mental health is not much different from zero.

At the risk of some inside baseball, sometimes scholars claim there is an effect by focusing on bivariate correlations. These tend to artificially inflate effect size estimates by failing to control for relevant confounding variables. For instance, when examining links between social media and mental health, it is necessary to control for sex, preexisting mental health, family stress and abuse, etc. By failing to do so, some scholars promise more than they can deliver. This is a social-science wide problem, but it does affect social media research.

Moral Panic

Somehow, we have to learn from prior moral panics on everything from video games to comic books to rock music to the radio. In each case, some scholars and politicians claimed big harmful effects and proposed censorious legislation. We’ve entered a similar cycle with social media. It’s already clear that focusing on social media won’t help youth. Instead, we should be focused on troubled families, which appear to be the main source of our youth’s problems.

Chris Ferguson, PhD, is a Professor of Psychology at Stetson University. He has clinical experience particularly in working with offender and juvenile justice populations as well as conducting evaluations for child protective services.