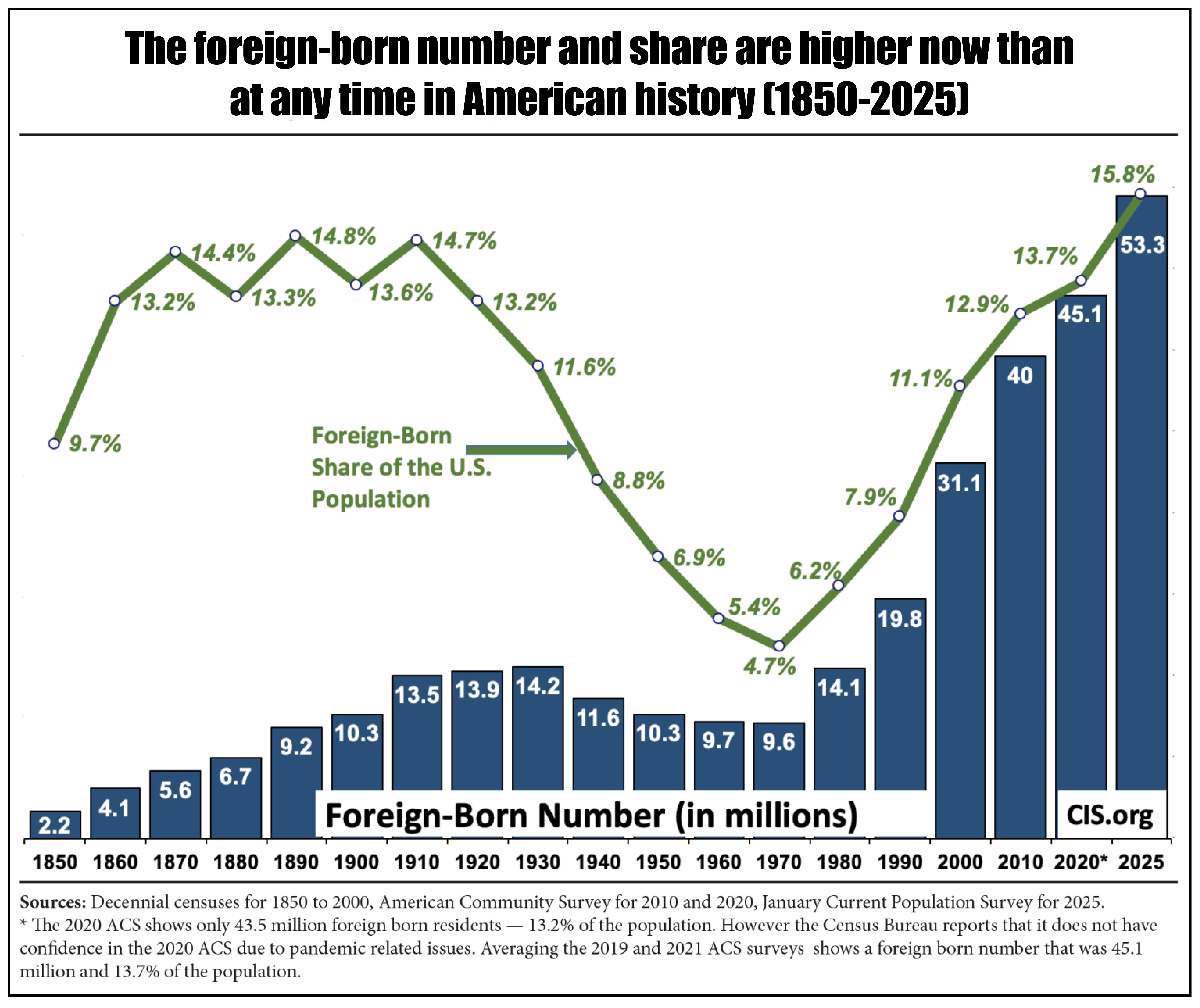

By adding millions of people to the population, immigration impacts everything from the economy and federal treasury to culture and politics. At the start of 2025, the total legal and illegal immigrant population, or “foreign born” in Census Bureau parlance, is higher now than at any time in our history. Therefore, it is not surprising that the issue has been roiling our politics.

The last “great wave” of immigration saw the number of individuals who were born in a foreign country hit record highs of 14.8 and 14.7 percent of the U.S. population in 1890 and 1910, respectively. America’s entrance into World War I, followed by restrictive legislation in the early 1920s, caused immigration to decline significantly. By 1970, less than 5 percent of the U.S. population was foreign born.

A liberalizing reform in 1965, combined with subsequent refugee crises, a major amnesty in 1986, and another expansionist law passed in 1990, increased legal immigration further. Increasing legal immigration, coupled with rising illegal immigration at the same time, caused the total foreign born population to more than quintuple from 9.6 million in 1970 to 53.3 million by January of 2025. Over the same time, the immigrant share of the population more than tripled to 15.8 percent — the highest percentage ever recorded.

The fastest growth in the foreign-born population over a four-year period occurred during the Biden Administration, when the number of those born in another country increased by 8.3 million — more than in the preceding 12 years.

The fastest growth in the foreign-born population over a four-year period occurred during the Biden Administration, from January of 2021 to January of 2025, when the number of those born in another country increased by 8.3 million — more than in the preceding 12 years. New arrivals are offset by outmigration and deaths among the existing immigrant population, which means for the foreign-born population to grow 8.3 million, something like 12 million new legal and illegal immigrants had to arrive during that period.

America has a very generous legal immigration system. Based on the January 2025 household survey, collected by the Census Bureau, I estimate there are 38 million legal immigrants — including naturalized citizens, lawful permanent residents, foreign students, and guest workers – present in the U.S. I also estimate there are 15.4 million illegal immigrants in the same data. Assuming only a modest share are missed by the survey, about 16 million illegal immigrants now reside in the country — an increase of more than 50 percent in just four years.

There is no mystery as to why the immigration surge occurred. It was a policy choice. Biden ended the Asylum Cooperative Agreements with Central American countries, terminated the Migrant Protection Protocols (also called Remain in Mexico) for asylum applicants, instituted catch and release at the border, and cut back on interior enforcement.

As the asylum system and immigration courts became overwhelmed, ever more people showed up at the border in the hope that they, too, would be released with a court date years in the future. The administration released 7 million inadmissible aliens into the country, including 530,000 flown in under a special “parole” program. Added to this are those who snuck across the border successfully or overstayed a temporary visa.

There is no mystery as to why the immigration surge occurred. It was a policy choice.

The role that policy played in causing the crisis was made clear when the administration changed course a few months before the November election, and border encounters plummeted. In February of this year, Trump’s first full month in office, encounters were down 94 percent from a year earlier. Trump’s rhetoric, the reversal of Biden’s policies, and pressure on Mexico to interdict migrants caused the influx to virtually cease.

Immigration is not an inexorable fact of nature. It is a policy choice, and that choice has consequences. Consider the fiscal situation. The National Academy of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine’s 2017 study is still the most comprehensive look at how immigration affects public coffers. Of the eight different fiscal models the National Academies analyzed, all showed a negative impact of immigration in the present. Their long-term projections, which require a lot of assumptions, produced mixed results.

The fiscal drain is primarily caused by two groups: legal immigrants who have no education beyond high school, and illegal immigrants. Well-educated immigrants tend to earn relatively high wages, pay a good deal in taxes, and make only moderate use of public services. The opposite is generally true of immigrants with low levels of education.

The economic impact of immigration is distinct from the fiscal impact. There is no question that immigration increases the aggregate size of the U.S. economy by adding workers and consumers. At the same time, because immigrants tend to earn lower wages than those born in the U.S., their entry into the population lowers per capita GDP. But neither of these facts are an indication of whether immigration benefits or harms the American people.

Probably the best way to think about the economics of immigration is to recognize that it creates both winners and losers. By increasing the supply of workers, immigration tends to lower wages for workers, but it also increases profits for businesses and lowers prices for consumers. These impacts are uneven, however. For example, 37 percent of construction workers are foreign born, roughly half of whom are illegal. By contrast, only 9 percent of those in legal professions are immigrants, virtually none of whom are illegal. Immigration creates relatively little competition for lawyers, so the economic impact for them is mostly upside. On the other hand, immigration clearly makes construction workers worse off.

Of course, the magnitude of all of these impacts depends on the scale of immigration. Reduce immigration, and the impacts will be correspondingly smaller. Therefore, any discussion of immigration policy needs to begin with an appreciation that the number of immigrants in the country and their share of the population are at record highs.

If the goal is to improve the fiscal balance and avoid negatively impacting lower-wage workers, then enforcing laws against illegal immigration and inviting a smaller and more selective class of legal immigrants is the right approach.

Steven A. Camarota, Ph.D., is Director of Research for the Center for Immigration Studies.