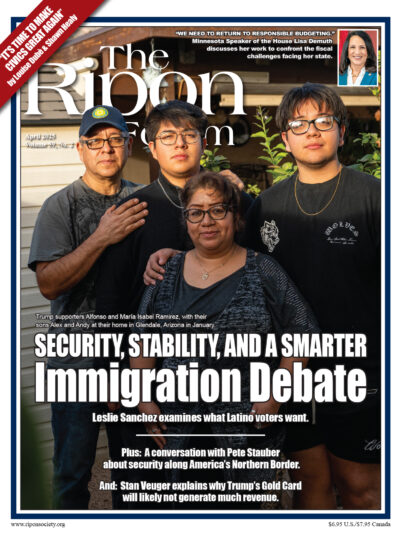

In September, Senator Edmund S. Muskie, speaking in seeming disregard of his political interests, said that a black running mate would harm the cause of civil rights and of his own electoral success. This statement was generally accepted as an honest recognition of the political facts of life both by black leaders, including Charles Evers of Mississippi, and by most other observers, including the conservative columnist William F. Buckley, who had earlier been on record advocating a black presidential candidate by 1980.

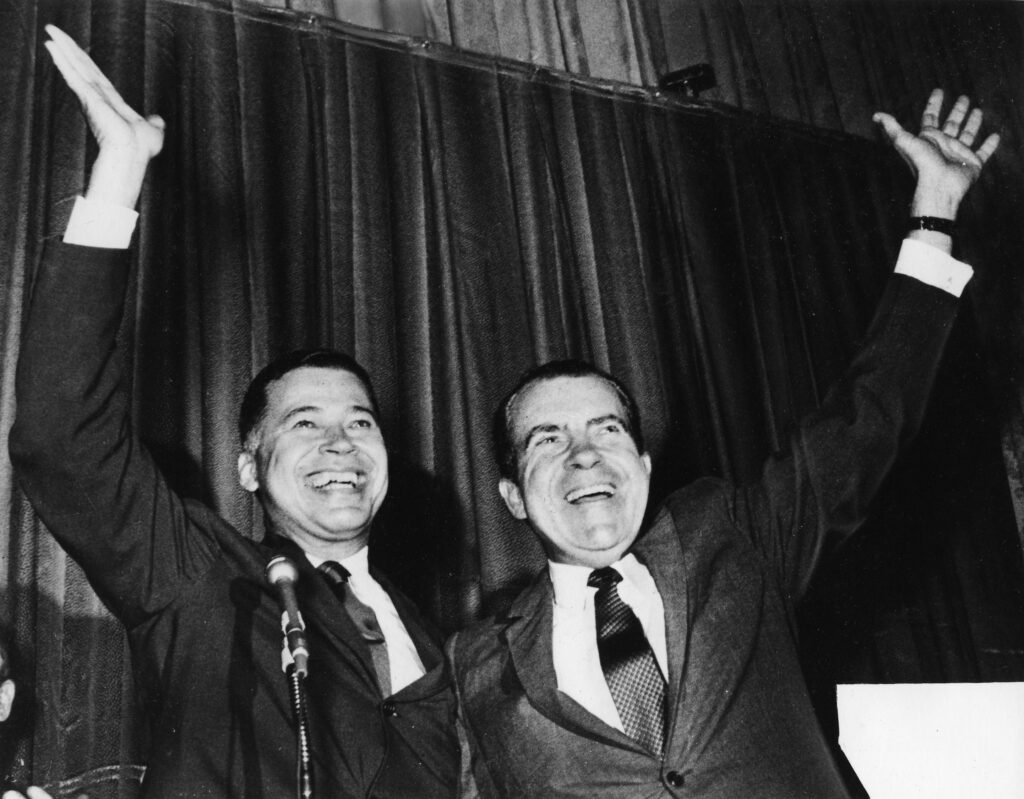

Richard Nixon responded immediately to Muskie’s remark with an effusive statement in praise of his own party’s leading Negro, Senator Edward Brooke of Massachusetts. Brooke’s position as the most popular politician in his home state, his landslide victory in 1966 with an electorate of which only 2 percent were of his race, and his prospects for easy reelection in 1972 showed, the President said, that the American public could disregard race and vote on a candidate’s qualities as a man. Republican Senate leader, Hugh Scott, followed a day later with an outright endorsement of Brooke for Vice President, as did Congressman Paul N. McCloskey, who is challenging the President in the New Hampshire primary. Spiro T. Agnew, the incumbent vice President, told reporters that he thought “Ed Brooke could be elected vice President.” All these Republican statements were either forgotten by the national press or dismissed as the usual self-serving political rhetoric, contrasting sharply with Muskie’s candor on the issue.

Except by the columnists Evans and Novak, who are among the nation’s most astute observers of day-to-day party politics. They tested the effect of a black vice presidency in a straw poll in Westchester county and found that whereas a black running mate like Carl Stokes hurt Muskie, Nixon was actually aided among white voters by having Brooke on the ticket. Their article suggested what I shall argue is indeed the case: that Muskie did give voice to a simple political fact, but one that is true only for the Democrats. A black vice-presidential candidacy would indeed be a disaster for them, but the same candidacy could actually help Richard Nixon.

Thus, far from embarrassing Muskie, the attention given to his statement helped to entrench him as the Democratic front-runner, while rhetoric about Ed Brooke, far from being merely idle talk by Republicans, opens up a realistic option for the President which deserves to be discussed at least as seriously as current gossip about retaining Agnew or replacing him with such men as Connally, Rockefeller, Reagan, Rumsfeld , Scranton, Morton, Javits, Bush, Taft, Stafford, Dominick, Milliken, Baker, Buckley, Cook, Volpe, Romney, Brock, Richardson, Dole, Cahill, Sargent, Lugar, Ruckelshaus, Laird, Gurney, or Holton.

To see why a Nixon-Brooke ticket is a realistic political possibility one must remember that the voters with the strongest racial feelings about blacks are Democrats, not Republicans.

To see why a Nixon-Brooke ticket is a realistic political possibility one must remember that the voters with the strongest racial feelings about blacks are Democrats, not Republicans. The Democratic national constituency stands upon four pillars and forms a house divided on civil rights. It is based on: 1) white southerners who traditionally have been suspicious of civil rights gains; 2) blue collar northerners who, though remarkably free of racial malice, have become leery of the civil rights movement because they have borne the major burdens associated with black migrations into Northern cities; 3) blacks, themselves, who have a strong sense of grievance about the inadequacy of civil rights gains; and 4) younger business and professional people, who often vote Republican in statewide elections but have begun moving Democratic in national elections because of the GOP’s lack of positive leadership on domestic reconciliation.

A House Divided

Thus, the four voting groups that are most important to the Democrats split up the middle on the issue of civil rights. This is the reason that national Democratic standard bearers must outflank any Republican attempt to give prominence to race and the social anxieties that are related to it in the voter’s mind. Race can only split the New Deal alliance, whereas economic issues inject new life into this old, but not yet dead, coalition.

Republicans, on the other hand, as befits the party that abolished slavery and then was carried away a century later by a Southern strategy, are now in a middle position between the Democratic factions on civil rights. As a party that is largely middle class, small-townish, white and still overwhelmingly northern and protestant, the GOP has had few of the fears about integration that afflict lower middle class Democratic constituents. But as believers in an ethic of self-reliance and private initiative, Republicans have also been less enthusiastic than black and upper middle class Democrats about government intervention to advance black progress. Daniel Patrick Moynihan’s use of the phrase “benign neglect” thus captures something important about Republican attitudes towards questions of racial equality.

This approach, of course, was somewhat less prevalent in the GOP ten years ago when the Nixon/Lodge ticket won 32 percent of the non-white vote, a majority of the business and professional vote, and when it was John F. Kennedy who won the Deep South and then paid off his supporters there with atrocious appointments to the Southern bench. But benign neglect is perhaps dominant now, since in the past decade the Republican constituency in most states, though still basically benign toward blacks, has both shrunk and become more neglectful of its party’s civil rights heritage.

Risking Defections

In its present reduced state, with only 25 percent of the voters calling themselves Republican and an ominously low and aging 31 percent of professional and business people, the Republicans are in an unenviable position. Unless the GOP can eliminate the economic issue that holds the Democrats together, it is tempted to pander to racial prejudice to divide the Democrats. The perils of this position are enormous. Since most Americans believe that it is wrong to exacerbate racial tensions, any toying with the racial issue will endanger the Republican party’s increasingly tenuous hold on its traditional middle class supporters. Besides, because Republicans stand in the middle of the road on civil rights, any concerted movement either against integration or for federal intervention risks a defection from their own ranks.

Republicans, as befits the party that abolished slavery and then was carried away a century later by a Southern strategy, are now in a middle position between the Democratic factions on civil rights.

To get a feel for the numbers that discipline Republican strategy, some recent statistical work by David Ballard, a Harvard Business School student, is helpful. Ballard used the data of the Michigan Survey Research Center to examine the civil rights attitudes of the 1968 voter. He found that several civil rights questions were asked that enable one to rank voters attitudes in an ascending scale from strong racial prejudice to strong integrationist sentiment. Such a scale, though still rough, provides a better sense of the graduation of prejudices and their susceptibility to leadership than one or two Gallup poll questions.

Only 10 percent of the American public were willing to tell pollsters that they disliked Negroes as a group (and this is roughly the same number who regularly say that blacks should be excluded from jobs regardless of individual qualifications). This vote, doubtless a few percentage points higher than that given to pollsters, may legitimately be called an apartheid vote or, to employ a much overused label, “racist.” Next on the scale comes the issue of open housing: 79 percent of the 1968 voters agreed that “Negroes have a right to live wherever they can afford to, just like everybody else.” Sixty-five percent agreed to the next question, that “the Federal Government should support the right of Negroes to go

to any hotel or restaurant they can afford.” Those who passed these two questions can be called “moderately integrationist.” Fifty percent, the “integrationist” vote, thought that the government “should see to it that white and Negro children go to the same schools.” Finally, only ten percent qualified as “strongly integrationist” by asserting that the civil rights movement was progressing too slowly.

Scaling the Electorate

Ballard found that one’s answers to questions scaled naturally (on what is called a Guttman Scale) so that those who failed the first question failed all the others, and those who passed the third generally passed the preceding two, and so forth. The gradations he devised enable us to divide the electorate roughly into those 10 percent who are strongly integrationist, the 40 percent who are integrationist, the 29 percent who are moderately integrationist, the 11 percent who are non-integrationist and the remaining 10 percent who may legitimately be called racist by virtue of their desire to judge a man by color alone. In national elections, the 10 percent of the population who are strongly integrationist are strategically much more important than the racist vote. Not only are they richer and more influential but they also contain a far higher proportion of ticket splitters who switch between the two parties. The racist voter, drawn from the ranks of older and less educated citizens, tends either to vote a straight party line, regardless of the issues or personalities involved, or to cast a protest vote for a third party “populist” candidate and thus reduce his leverage over the major parties.

Ballard also devised a somewhat rougher scale to measure attitudes toward the welfare state, in which he classed voters as “liberal, moderate and conservative,” depending on their desire to see the Federal government take an active role in such questions as aid to education, medical care, and full employment.

Conservative and Integrationist

The results on these two scales may be summarized as follows: 1) Among white voters, the Nixon constituency in 1968 was integrationist on civil rights, and had more integrationists than the white constituencies of Humphrey and Wallace combined. At the same time it should be noted that Humphrey had a majority of strongly integrationist whites and of blacks, almost all of whom are integrationist, so that with black voters included, Humphrey’s constituency was more favorable to civil rights than Nixon’s. 2) The Nixon constituency in 1968 was “conservative” (i.e. against government intervention) on social welfare issues and had more conservatives than the Humphrey and Wallace constituencies combined. 3) Nixon’s 1968 constituency was closer to the mainstream of Americans on both civil rights and social welfare issues. The American public as a whole leans toward racial integration but is skeptical about major extensions of the welfare state. Wallace’s constituency leans against the consensus on civil rights, Humphrey’s on the welfare state.

These three points will explain some of the contradictory strains in Mr. Nixon’s centrist position, and also throw light on some mistakes he has made thus far. Until the spring of 1971, he improvised on the advice to Republicans in Kevin Phillips’ book, The Emerging Republican Majority, which held that the GOP should keep the racial issues alive through unabated federal enforcement of the laws, but use other political means to encourage those who were alarmed by black gains to enter Republican ranks. The political logic that can justify such an approach is that one might limit one’s losses among the better educated voters with integrationist policies, while one might attract the less educated, more naïve voter with rhetoric. Hence John Mitchell’s oft-quoted maxim, “Watch what we do, not what we say.”

Words and Deeds

But it is in fact the more verbal, college educated voter who is most impressed with words. It is the lower middle class voter, with his suspicion of politicians, who waits for deeds before questioning his national party affiliation. Phillips’ own willingness to recognize this fact came slowly because of his desire to see the Republican Party become both a majority and more “conservative.” The only source of available “conservative” voters seemed to be Wallace supporters. His book thus continued a longstanding disservice to the conservative cause by making it seem synonymous with the recruitment of racists and non-integrationist protest voters on terms unacceptable to most Republicans. As he became aware of this difficulty, Phillips began to question the polarizing rhetoric he had previously applauded as part of a new “populist” conservatism. He laid increasing emphasis on attracting Wallace supporters with positive programs, but these tended to be New Deal style spending and subsidy projects that unfortunately run counter to the anti-interventionist strains in the GOP.

An issue on which Phillips’ approach might have succeeded was in federal measures to integrate housing, but here l’ve used a term, which the President prematurely took up, that pointed up the fundamental contradiction in the Nixon constituency. The phrase was “forced integration.” It was ill advised because, though the Nixon constituency was against government force, it was for integration. Mr. Nixon first tried to explain that his opposition to “forced integration” should not be construed as opposition to integration itself, but finally he just dropped the term altogether and acquiesced in George Romney’s modified Open Communities program. This shift marks the end of Phase I in Republican use of the racial issue, which might be called the “deeds versus words” phase. Since then, Mr. Nixon has tried to align deeds and words more closely.

Phase II, which might be called “crime not race,” begins with the President’s speech announcing his two Supreme Court nominees. The Boston Globe reported that Edward Brooke was explicitly offered one of these two seats, so that it may have been the President’s original intention to present a Poff-Brooke ticket to the Senate. He may have hoped that Brooke’s acceptance would have led to the retirement of the aging Thurgood Marshall who would then have been replaced with a law and order conservative. Had these three appointments occurred it would be widely accepted that Nixon had somehow changed his political emphasis. As is, the very careful wording of his speech announcing the appointment of Powell and Rehnquist will have to suffice as evidence of the new emphasis:

“In the debate over the confirmation of the two individuals I have selected, I would imagine that it may be charged that they are conservatives. This is true, but only in a judicial, not in a political sense …

“As a judicial conservative, I believe some court decisions have gone too far in the past in weakening the peace forces as against the criminal forces in our society … And I believe we can strengthen the hand of the peace forces without compromising our precious principle that the rights of individuals accused of crimes must always be protected. …

“Let me add a final word. . . . I have noted with great distress a growing tendency in the country to criticize the Supreme Court as an institution. Now, let us all recognize that every individual has a right to disagree with decisions of a court. But after those decisions are handed down, it is our obligation to obey the law, as citizens to respect the institution of the Supreme Court of the United States.”

The message is unmistakable: “Our obligation to obey the law” applies to issues of integration as well as crime. Nixon has delivered to the conservatives on the latter, by changing the balance of the Court towards judicial conservatism. Those whose political conservatism demands a further pandering to anti-integrationist sentiment had best shop elsewhere.

Some credit for bringing Mr. Nixon to this change must go to two veteran Democratic campaign analysts, Mssrs. Scammon and Wattenberg, authors of The Real Majority, published well in advance of the 1970 elections. This book was summarized in loving detail for White House strategists, who somehow failed to recognize that it was designed as a handbook for Democrats, not for them. It pointed out that as the economic issues essential to the New Deal coalition receded, a social issue, of which race was only one strain, had come to the fore. If Democrats stuck only to the economic issue, Republicans might split their coalition on the social issue. But if Democrats neutralized the GOP on the social issue, they would still have a residue of trust on bread-and-butter concerns to see them through. With careful clustering of poll results Scammon and Wattenberg were able to show that Democrats could have all the advantages of the social issue without any hint of race. Their message: come out four square for law and order but purge this issue of any racial overtones. The White House approach, on the other hand, was better reflected in a memorandum which Murray Chotiner sent to Republican Senatorial candidates. He urged them to try to get their opponents to take a stand for or against busing. Either way, they lose, Chotiner observed.

Polarizing Style

Because Republican campaigners were less than scrupulous with their rhetoric on the social issue, their use of it alarmed middle class voters who put a high value on reconciliation _between races and generations. These voters perceived Republican rhetoric as “divisive.” The results were that Democrats made important inroads in affluent Republican suburbs, retained the black vote, and even won a majority of the Wallace constituency in every Southern state, including South Carolina, where Albert Watson, with the campaign assistance of David and Julie Eisenhower, ran a losing gubernatorial strategy by denouncing the “bloc vote.”

Mr. Nixon, returning from a European trip in the last weeks of the campaign, identified himself with the polarizing style that he had hitherto left to his vice President. He did succeed in making strident rhetoric seem legitimate to some voters, who actually returned to the Republican fold because of his campaign efforts, but he also demeaned his own office in the minds of others and put many of his own supporters in a difficult bind in which their respect for the office of the Presidency and their loyalty to the Republican Party conflicted with their craving for a moderate political style.

The one belated lesson which the President seems to have taken from this campaign is that in a national constituency, he dare not get too strident without scaring some of his own supporters. Moreover, having been outmaneuvered on the social issue by the Democrats, he learned the real lesson of Scammon and Wattenberg: any benefit that can be gained from the social issue he can have with a calm approach on crime alone. The minute any hint of malice is attached to it, the President loses. Many Americans will of course continue to exhibit some level of unease about the extraordinary progress in civil rights during the past decade, and some will vote their racial prejudices in local elections. But in a national election the most important swing voters will not tolerate a President who associates himself, however indirectly, with the seamier passions in American life.

If Mr. Nixon has learned this lesson, some of his aides have not. One can accordingly expect them to try to align the President with plans to use the busing issue to partisan advantage, even to the extent of soliciting presidential support for an antibusing amendment to the constitution. It will be a test of Mr. Nixon’s new phase if he resists such pressures to emphasize that his major priorities in the social sphere are “crime not race.”

From this stance to putting a black on the ticket is a large step that depends on events that cannot now be foretold. But it is a plausible step for Mr. Nixon, though one that must overcome some standard objections from both his friends and his enemies.

Some Standard Objections

Some of his enemies will hold that he would not do such a thing because he is himself racially prejudiced. They neglect the distinction between entertaining racial prejudices oneself and seeking support of voters who have them. Mr. Nixon’s own personal feelings are probably best explained by Gary Wills’ designation of him as a “self-made man,” propelled by a small-town Protestant ethic of hard work, individual initiative and self-reliance. This ethic may have its blind spots, but racism is not one of them. In the Republican Party as a whole, Mr. Nixon’s impact has been to loosen prejudices by appointing southerners, Catholics, Jews, Mexican-Americans and blacks to unaccustomed positions. This is significant because the Republican Party is overwhelmingly northern, white and Protestant. For the Democrats, who are a coalition of regional, ethnic and religious minorities, such appointments have come naturally. What qualifies as drama within the stuffy confines of the GOP, may not seem a very big thing in the headier air outside, but it may be sufficient to suggest that Mr. Nixon is himself trying to reach out from the traditional constituency of his party.

Some of the President’s friends will object that race still remains so explosive an issue that putting a black on the ticket will be tantamount to writing off the South, in which Mr. Nixon received 61 electoral votes in 1968, that it would tear the country apart, that it would cause a bolt by conservative Republicans, that it would lose the election for Mr. Nixon.

Many Hats

Certainly, if Mr. Nixon put Angela Davis or Eldridge Cleaver on the ticket, all these things would happen. But we are talking here about Senator Edward M. Brooke of Massachusetts, a man whom the President reportedly offered cabinet and Supreme Court positions, who is the Senate’s expert on arms control, who was campaign manager for Senator Hugh Scott in his successful race for Republican Minority leader. Brooke has been described by a Southern colleague as “the most graceful man on the Republican side of the Senate,” by Professor John S. Saloma of MIT, an authority on the Congress, as the most successful Republican Senator in the class of 1966, which includes such men as Charles Percy, Mark Hatfield, Howard Baker Jr., and Robert Griffin. In his early days in Massachusetts he used to call himself a conservative, a label that he can no longer accept in public so long as conservatives themselves fail to make clear that it is not a synonym for racial prejudice. He has appeared regularly at Republican dinners in the South and has campaigned with his wife, an Italian war-bride, before every kind of audience in his home state, whose politics are dominated by what are thought to be “backlash” ethnic groups.

Brooke has been described as the most successful Republican Senator in the class of 1966, which includes such men as Charles Percy, Mark Hatfield, Howard Baker Jr., and Robert Griffin.

If he were put on the ticket after an arms control agreement with the Soviet Union, it would be because he had earned it. If he campaigned in defense of the President’s increased spending to make law enforcement into a respectable profession, it would be because as a former Attorney General of Massachusetts he believed in it. If he appeared with the President in open air cars in such cities as Memphis and Dallas, it would not be a symbol of racial turmoil but of reassurance that America was on its way back to social peace. Conservative Republicans might object to liberal aspects of his voting record, but cognizant of their need to guard against an unfair interpretation of their own motives – and these motives are not racial – they would be best advised to become Senator Brooke’s vocal supporters.

Increased Sales

Among the voting public, there can be no sure predictions about the impact of a Nixon-Brooke ticket, because as the Senator observed on a Boston radio program, “We will never know until it has been tried.” Properly executed, such a ticket would probably produce an effect somewhat like that experienced by the first companies that included black models in advertising their products: a wave of angry protest coupled with much favorable comment, and when the dust had settled, increased sales. A Nixon-Brooke campaign, with Vice President Agnew, Barry Goldwater, and Ronald Reagan adding their support to it, will probably have the following results:

About 18 percent of Mr. Nixon’s 1968 supporters who are non-integrationist or racist will have attitudes ranging from extreme discomfort to fury. Perhaps two-thirds of them can be mollified by appeals to Party loyalty, to Nixon’s record in office, or to Brooke’s merits as a man. The rest will split between Wallace and Muskie, if he is the Democratic nominee. Their effect can be counterbalanced in the North by increased gains among racially tolerant young people and suburbanites, who have been most enthusiastic for Brooke in his home state. In the South, the President can count on support among the many moderate Southern blacks who already give his administration favorable ratings. In the North, where his percentage of black approval is much lower, his advantage may consist in part in a low black turnout for his opponent. On the whole, Mr. Nixon can prudently count on a change from his 8 percent share of the black vote in 1968 back to the 32 percent he gained in 1960. To make similar gains in any other group Mr. Nixon would have to write off a large part of his Republican base.

A Machiavellian Trick?

A Nixon-Brooke ticket may make George Wallace run with a vengeance, in which case he will draw off racist protest voters, the majority of whom are Democrats. This can bring Wallace up to his 1968 totals, but probably not much higher. Nixon would continue to attract responsible southern voters by running on his record. The Democratic nominee will be best advised to run on the economy, even if this has improved from 1970, and on Nixon’s personality. Some of the more partisan Democratic campaigners will also try to revive the “tricky Dick” image, with its implication that the selection of Brooke was a Machiavellian trick. The credence swing voters give to this will depend on the evidence. If they are convinced that Nixon’s and Brooke’s positions on foreign and domestic affairs are not too different, that Brooke has in some way earned a spot on the ticket, and that the effect of his presence will be to promote national reconciliation, they will reelect the President. If not, they probably won’t.

For Mr. Nixon and the advertising men who advise him, a credible ticket of this sort is difficult to stage manage, because, when all the political calculations are done, there remains in it a dimension of moral leadership that cannot be faked.

The country has made extraordinary progress in racial attitudes over the past decade. But there remains a good fifth of the population who do not yet accept integration as a desirable goal; half of these are hard-core racists who are willing to judge a man by his color alone. The effect of these voters on our politics has been minimized by their party-line voting habits and their hankering after protest candidates. Such predictable responses make a Nixon/Brooke ticket politically feasible in 1972. But twenty percent of the electorate is too big a group to dispose of with mere cleverness, especially since their attitudes differ only in degree from those of others. Though the President would be wrong to allow even a whisper of reticence about the country’s irrevocable commitment to racial equality, he does, as President, have an obligation to assure a measure of dignity to those citizens who feel themselves undermined by the social trends that have accompanied the drive toward civil rights, but which are distinct from it. In the 1970 and 1971 elections, moderate Southern Democrats found that “a little man’s” approach could reassure these voters without the usual race-baiting. A new breed of Southern Democrats has stressed the common concerns of black and white citizens with irresponsible large corporations, corrupt government, poor government services, and of course the usual bread-and-butter issues.

There is not enough in Mr. Nixon’s record or bearing to enable him to espouse convincingly such a modified populism. But in three areas he has been sensitive to the problems of what he has called the Forgotten Man: crime, patriotism and the responsiveness of government. His difficulty in each of these areas has been that years of pitting rivals off against each other in the political arena have habituated him to using issues to divide rather than unite; his political aides, attuned to the nuances of his own feelings, often magnify these weaknesses. Thus, the use of the crime issue in 1970 was so demagogic as to have divisive overtones. The flag-waving praises of America’s men in uniform seemed to college students to contain a note of reproach toward the “bums” who were not serving. Mr. Nixon’s espousal of responsive government, a genuinely unifying issue, stopped at the enunciation of a disembodied slogan about a “New American Revolution;” the Nixon staff could think of no actions to back it up beyond a few regional press conferences – a feeble gesture at “grass roots” government.

Moral Leadership

The question of moral leadership implicit in the success of a Nixon-Brooke ticket, then, is whether Mr. Nixon can overcome the habits of two decades to provide a concrete symbol that will reassure the whole country rather than further divide it for partisan gain. He cannot do this without making law and order an issue in 1972, since this is one important domestic issue on which he can point to increased spending and other measures of performance. He cannot do it without reasserting his commitment to the essentially patriotic rationale of his phased withdrawal from Vietnam, with its emphasis on saving face and not admitting that American boys have died in vain. Nor can he reassure the country if Senator Brooke is thought to have been chosen for his race rather than for his qualities as a man. But the real question will be whether he can muster the sense of purpose to show that racial justice, a desire for peace overseas and a firm approach to crime, drugs and unrest all fit into a coherent vision of America.

The reader may take comfort in knowing that one will be able to answer this question for oneself well in advance of the Republican nominating convention. Though White House reporters like to emphasize the high drama in any shift of policy, presidents rarely undergo sudden conversions. Usually the ground is prepared by innumerable small statements and policies in which many people have a part. The President’s “dramatic turnaround” on China, for example, was the result of patient State Department work from the very beginning of his administration, and it involved important contributions by many outside experts, journalists and businessmen as well.

A Nixon/Brooke ticket gives the GOP a chance to ratify this progress and channel the drive toward civil rights in ways consistent with its own philosophy.

If a Nixon-Brooke ticket is a viable option, the message will be clear from his staff’s willingness to signal an irrevocable commitment to racial integration. This means that they will allow to circulate pictures of some of the President’s meetings with biracial groups, that they will willingly schedule such meetings, that they will publicize the administration’s commitment to stepping up the pace of integration in suburban housing and in the labor force, or publicize the innumerable small acts in the cause of racial reconciliation that regularly come out of the administration. It also means continuing emphasis on the President’s attempts – with Brooke’s support – for arms control (perhaps with a role for Brooke in the forthcoming Moscow trip) and a firm but not demagogic position on crime and unrest. It would mean, in sum, a transition into Phase III of the Nixon administration’s politics, which in deference to the President’s new use of “peace forces” to mean police, might be labelled: “peace – at home and abroad.”

The President’s two other options are to remain in Phase II with Agnew (or a more calming replacement) or to retrogress to Phase I with a demagogic use of the school busing issues. There will be supporters for both of these competing strategies within his party, and they will try to foreclose a Nixon/Brooke ticket. The President will probably have no choice but to let conflicting signals emerge while he busies himself with his still shaky position in foreign and economic affairs. No matter what the outcome, Mr. Nixon has neither the desire nor the power to alter this country’s considerable progress toward racial tolerance. A Nixon/Brooke ticket gives the GOP a chance to ratify this progress and channel the drive toward civil rights in ways consistent with its own philosophy. This would mean emphasis on integration of labor unions, black business enterprise, community self-determination, home ownership, welfare reform, ghetto law enforcement, early childhood development, and fair-h0using. These programs, incidentally, represent new frontiers for the civil rights movement.

The GOP can, on the other hand, cynically encourage a fifth of the nation in the vain hope that the President can negate the profound moral change in racial attitudes that has occurred. In this matter of social mores, as in so many others, the President is not so influential a person as those who teach small children, but what he does within the political calculus appropriate to his office can make a difference. Since Senator Brooke is the only black elected official of presidential timber, and since the GOP is in a unique position to benefit from a biracial ticket, 1972 presents Mr. Nixon with a rare opportunity to fulfill his original pledge to ”bring us together.”

© 1972 by Josiah Lee Auspitz