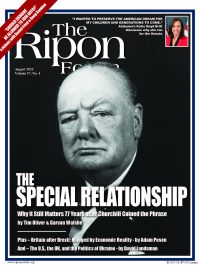

On March 5, 1946, Winston Churchill traveled to the United States to deliver a speech at Westminster College in Fulton, Missouri. It was a time of transition for both Churchill and the world.

The previous summer, in July 1945, he had been unceremoniously voted out of office as British Prime Minister less than a month after leading his country to victory in World War II. The war over, the world stood on the precipice of a new epoch – a Cold War.

Churchill’s objective that day in Fulton was to define the new epoch. An

d he did just that. The address he delivered will long be remembered as the speech that introduced the term “Iron Curtain” to the world. “From Stettin in the Baltic to Trieste in the Adriatic, an Iron Curtain has descended across the Continent,” he famously declared.

But the address will also be remembered as the speech that introduced another term to the world – “the Special Relationship.” “Neither the sure prevention of war,” the Last Lion stated, “nor the continuous rise of world organization will be gained without what I have called the fraternal association of the English-speaking peoples. This means a special relationship between the British Commonwealth and Empire and the United States.”

Seventy-seven years later, the Iron Curtain has fallen, but the Special Relationship remains. With war once again raging in Europe, and threats from China and elsewhere rising in an increasingly volatile world, it is a good time to look at origins of the Relationship and why the U.S.-UK alliance remains so critical to global peace and security today.

World War II (1941-1945)

If the Special Relationship between the U.S. and UK took root with Churchill’s speech in Fulton in 1946, one could argue that the seeds of the relationship were planted with a visit the British Leader made to Washington in 1941.

It was December 22 — three days before Christmas and 15 days after Japan’s stunning attack on Pearl Harbor. Churchill arrived at the White House after a cold and foggy Atlantic crossing aboard the Duke of York, eager to establish a new relationship with President Franklin D. Roosevelt.

He ended up staying at the Executive Mansion for three weeks, celebrating the holidays with FDR and Eleanor and, as writer Erick Trickey recounted in 2017, bonding with the President “over late-night drinking sessions that annoyed the First Lady, taxed White House staff, and cemented the partnership that won the world war.”

The bonds between the two nations were further cemented the day after Christmas, when Churchill became the first Prime Minister to address Congress. In a speech that was broadcast live over the radio both nationally and internationally and interrupted repeatedly by thunderous applause in the Senate chamber, Churchill boldly predicted the allies would prevail, saying “the British and American peoples will, for their own safety and for the good of all, walk together in majesty, in justice and in peace.”

If the Special Relationship between the U.S. and UK took root with Churchill’s speech in Fulton in 1946, one could argue that the seeds of the relationship were planted with a visit the British Leader made to Washington in 1941.

As both nations increasingly cooperated on the Pacific and European fronts to defeat Japan, Germany, and Italy, the seeds of the Special Relationship began to grow. British scientists joined Robert Oppenheimer and other American scientists working on the Manhattan Project. British and American pilots led joint air-raids across Europe. And a joint invasion of Northern Africa, Italy and Northern-France provided “the first broad hints,” as the Times reported, “that someday the two nations might draw together.”

By the end of the war, a formidable alliance had been forged that would outlast the initial conflict against fascism. In February 1945, meeting this time at the Crimean coastal town of Yalta, Churchill and Roosevelt, alongside Soviet leader Joseph Stalin, outlined a joint vision for post-war Europe. FDR declared that the emergence of “a new world order” spearheaded by the U.S. and UK’s joint commitment to “peace, security, freedom, and general well-being of all mankind.”

The Cold War (1945-1989)

With much of Europe in ruins and the Iron Curtain of Soviet totalitarianism seeking to broaden its reach across the continent, the burgeoning alliance between America and Britain became even more vital for the preservation of democratic order.

In the years following the war’s end, there was no greater symbol of the power and potential of democracies to be a force for good than the Marshall Plan. The United Kingdom would eventually become the largest beneficiary of the Plan, receiving over $3 billion in aid — or a quarter of the total funds provided. It was — both literally and figuratively — an investment in freedom.

In June 1948, the forces of freedom received their first real post-WWII test when Soviet forces blocked rail, water, and roadway access to Allied-controlled areas of Berlin. In the face of this aggression, the Special Relationship between the United States and United Kingdom would prove its worth. As part of the Berlin Airlift, the two countries joined together to conduct a total of 189,000 airdrops over the next year, delivering over 2.3 million tons of vital food and fuel to the people of West Berlin.

In the coming decade, not all tests of the Special Relationship would prove to be external. During the Suez Canal Crisis of 1956, for example, the U.S. and the UK found themselves on different sides of the conflict. The conflict began on July 26, when Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser announced that he was nationalizing the Suez Canal Company, a joint British-French enterprise which had owned and operated the Canal since its construction in 1869. The U.S. attempted to broker a peaceful settlement to the dispute. Britain, however, decided to work with France and Israel to launch a military strike against Nasser, whom the Israelis viewed as a threat. The strike took place on October 29, when Israeli forces attacked the Sinai Peninsula, advancing to within 10 miles of the Suez Canal. Two days later, Britain and France would send in troops of their own.

By the end of the war, a formidable alliance had been forged that would outlast the initial conflict against fascism.

The United States viewed the attack as an unnecessary distraction from another crisis that was then unfolding in Eastern Europe — the Soviet Union’s brutal suppression of an uprising in Hungary. In response, the Eisenhower Administration secured a resolution from the United Nations General Assembly condemning the invasion. It also sent a clear signal to their erstwhile British allies that they would not receive American support. Without this support, the handwriting was on the wall. Along with France and Israel, Britain withdrew their forces from the Sinai, bringing the crisis to an end.

If the Suez Crisis caused a certain chill in the Special Relationship between the United States and United Kingdom, it didn’t take long for the ice to thaw. Indeed, less than two years later, on July 3, 1958, the U.S. and UK signed the Mutual Defense Act, a bilateral treaty which paved the way for the two nations to share sensitive defense information related to nuclear weapons, naval nuclear propulsion, and nuclear threat reduction. Then-British Prime Minister Harold McMillan called this agreement the “great prize,” and it would go on to form the foundation for U.S.-UK defense cooperation that continues to this day.

This cooperation in the face of potential nuclear annihilation would prove vital four years later when President John F. Kennedy called on his longtime friend, then-British Ambassador David Ormsby-Gore, to help him navigate the diplomatic and military decisions he faced during the Cuban Missile Crisis. As Gary Ginsberg recounted in a July 2021 essay for Politico, the British Ambassador played a pivotal role in bringing the world back from the brink of Armageddon. “His proximity to the seat of power did not go unnoticed,” Ginsberg wrote. “Vice President Lyndon Johnson complained that ‘the limey’ was seated ‘front and center’ at a meeting of a steering group that week in the White House Situation Room, while he himself was ‘down in a chair at the end, with the goddamned door banging in my back.’ Afterward, Jackie described Ormsby-Gore’s presence then and later as ‘indispensable,’ adding: ‘If I could think of anyone now [after Jack’s death] who could save the Western world, it would be David Gore.’”

On July 3, 1958, the U.S. and UK signed the Mutual Defense Act, a bilateral treaty which paved the way for the two nations to share sensitive defense information related to nuclear weapons, naval nuclear propulsion, and nuclear threat reduction.

Perhaps it was this type of personal connection that allowed the Special Relationship to remain intact over the next decade, when successive U.S. presidents shifted their foreign policy focus away from Europe and toward other concerns — first the War in Vietnam, and then a more active confrontation of Soviet expansionism in the Middle East. By the late 1970s, the Special Relationship was described by B.J.C. McKercher, a Professor of International History and author of Britain, America, and the Special Relationship since 1941, as being “strategically faded,” even if it remained essential for peace in Europe.

This changed with the election of Margaret Thatcher as British Prime Minister in 1979 and Ronald Reagan as U.S. President a year later in 1980. Sharing common principles and a similar worldview, Thatcher and Reagan were natural allies who became fast friends. Looking back on their first meeting in 1981, Thatcher would later remark, “I knew that I was talking to someone who instinctively felt and thought as I did.” Calling each other “Maggie” and “Ronnie,” both leaders formed a close partnership that would prove instrumental in ending the Cold War.

The New International Order (1989-present)

In the years since the collapse of the Soviet Union, the Special Relationship has gone from being a partnership focused on stopping the spread of communism to an alliance that is attempting to maintain order in an increasingly volatile and chaotic world.

One could argue that the first test of that alliance came in 1990, when Saddam Hussein ordered Iraqi forces into Kuwait. President George H.W. Bush assembled an unprecedented international coalition of 39 countries to take action in response to this aggression. The coalition included Britain and other NATO allies, as well as the Middle Eastern nations of Saudi Arabia, Syria, and Egypt.

In the lead-up to the military operation that would come to be known as Desert Storm, Bush had a conversation with Thatcher who encouraged him to stay resolute in moving forward, famously telling him, “This is no time to go wobbly.” Bush held firm and the coalition took action, repelling Iraqi forces and liberating Iraq.

Eleven years later, the international order was shaken to its core when terrorists attacked the United States on September 11, 2001. One week after the attacks, President George W. Bush addressed a Joint Session of Congress to talk about the aftermath of the event, and the U.S. response moving forward. In a sign of how important the Special Relationship would be in that response, the only foreign leader in the House Chamber for the President’s speech that night was British Prime Minister Tony Blair, who was sitting beside First Lady Laura Bush in the gallery.

In the years since the collapse of the Soviet Union, the Special Relationship has gone from being a partnership focused on stopping the spread of communism to an alliance that is attempting to maintain order in an increasingly volatile and chaotic world.

In a letter to Bush the following July, Blair reiterated his support, writing: “I will be with you, whatever.” Eight months later, the United States, along with coalition forces primarily from the United Kingdom, invaded Iraq to end the reign of Saddam Hussein and confiscate weapons of mass destruction that were believed to be in his possession. Saddam was deposed and eventually executed, but the WMD — as the world knows — were never found.

Since that time, the Special Relationship between the United States and United Kingdom has been tested in a number of ways, from the passage of the Brexit referendum by British voters in 2016 to the election of Donald Trump as U.S. President later that same year. But just as meeting the threat of Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union gave the Special Relationship a meaning and purpose in the 20th century, so too are the threats of China and Russia giving the Relationship a new meaning and purpose today.

President Joe Biden said as much during a news conference with British Prime Minister Rishi Sunak at the White House this summer, describing the Special Relationship as an “unshakable foundation.” Biden reiterated this message during a visit to London the following month, when, during a meeting with Sunak in the garden at 10 Downing Street, he declared matter-of-factly, “Our relationship is rock-solid.”

Danielle Wagner is a Frenzel Fellow, while Fynn Haagen is an Oxley Intern at the Ripon Society.