Pennsylvania’s Medicaid reform efforts are still in the formative stages, with assorted models and numbers competing for attention and occasionally challenging the comprehension skills of average citizens. It is a difficult and intricate program, assembled like a watch but set to a time zone we long ago departed.

With its federal formulas, sliding scales and state-by-state eligibility quirks, Medicaid could well be called America’s dullest important issue.

So my administration is operating on two guidance principles:

1. Medicaid in Pennsylvania must be foremost about saving people.

2. We can save no one if the system is bankrupt and ineffective.

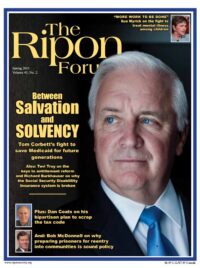

This balancing act between salvation and solvency presents challenges on a greater scale than many other states. While my Secretary of Public Welfare, Gary Alexander, hails from Rhode Island where he gained attention by shaping that state’s Medicaid reform, we really need a Pennsylvania model. Our population numbers and demographics demand as much.

With its federal formulas, sliding scales and state-by-state eligibility quirks, Medicaid could well be called America’s dullest important issue.

At present, Medicaid exists as a one-size-fits-all program, with little room to customize to the needs of a different group. More than 2.2 million Pennsylvanians use Medicaid and many of them are elderly or disabled – people with far different needs and aspirations and prospects than healthy users. As it now exists, Medicaid treats ailments but does little or nothing to prevent them.

And, perhaps most importantly, it traps people into an inflexible system in which they have no options.

Because federal funding is limited but the number of recipients is growing, the money paid to doctors for a Medicaid visit often means doctors won’t take those patients. One of the first questions asked by some receptionists when a prospective patient calls is whether they are medical assistance recipients. They don’t want them.

This is an utter inversion of the theory of patient choice. Instead of picking their doctors, too many Medicaid recipients end up looking for doctors who will pick them. This isn’t just bad medicine; it’s bad social policy.

The bad economics of the current Medicaid system is, perhaps, the only simple thing about it. Medicaid recipients do not especially care what their visit costs so long as someone else is paying. This is not an impulse unique to the disadvantaged. Common sense tells us that the more we are aware of the price of a service the more likely we are to become careful shoppers.

Pennsylvania intends to seek a waiver that will move more and more of the options for funding medical coverage for the poor into private-sector providers. The major problem our recipients have faced is access, a problem found in any number of states.

That standard of careful shopping must apply to states. Since its inception, the federal formula for Medicaid has provided a steady flow of dollars that assures that no state carries the entire cost. This has tempted many states to expand their programs when the economy and revenues are increasing. As the last recession has shown, that formula is one for fiscal disaster when it comes to open-ended entitlement programs.

The point of Medicaid is to be someone’s temporary medical insurance, not their lifelong provider.

So, the overall model we think most practical for Pennsylvania is a set grant to a Medicaid recipient from which he or she can choose from a menu of private medical insurance providers. This provides an incentive for providers to compete with each other by providing the best value for the available money while encouraging recipients to take charge of their own care and budgeting.

The trick to all of this is to get recipients to play their roles as consumers. The only way to do that is to create a system with plainly written rules, easily comprehended guidelines, and carefully crafted eligibility standards. The point of Medicaid is to be someone’s temporary medical insurance, not their lifelong provider.

One incentive to a healthier lifestyle could also include allowing a Medicaid user who is able to retain a healthy balance in his or her grant at year’s end to apply that money to something else inside the social welfare and needs system. The point of welfare programs is not to be permanent. We cannot risk making poverty an acceptable lifestyle.

Medicaid and how we confront its shortcomings will be an important measure of how this nation will frame its philosophical outlook for the next generation. One side would argue for universal care funded unceasingly and encompassing as many people as possible in as uniform a way as possible. The other would stress personal autonomy, a range of choices and as limited a role for government as feasible.

The first formula has been tried and now we face insolvency with no appreciable gains to show for it. It is time to consider the second. Doing nothing is not an option.

Tom Corbett is the Governor of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania.