For nearly 30 years now, author and attorney Philip Howard has been one of the leading voices for good government in America. His 1995 book, The Death of Common Sense, provided Republicans with a roadmap to reform the federal bureaucracy after they won control of Congress the preceding year. Similarly, his most recent book, called Not Accountable and reviewed in these pages last year, pointed to the “political power of public employee unions” as the source of government dysfunction, and recommended that public unions be declared unconstitutional as a way for the American people — and their elected leaders in Washington — to reduce dysfunction and regain control.

For nearly 30 years now, author and attorney Philip Howard has been one of the leading voices for good government in America. His 1995 book, The Death of Common Sense, provided Republicans with a roadmap to reform the federal bureaucracy after they won control of Congress the preceding year. Similarly, his most recent book, called Not Accountable and reviewed in these pages last year, pointed to the “political power of public employee unions” as the source of government dysfunction, and recommended that public unions be declared unconstitutional as a way for the American people — and their elected leaders in Washington — to reduce dysfunction and regain control.

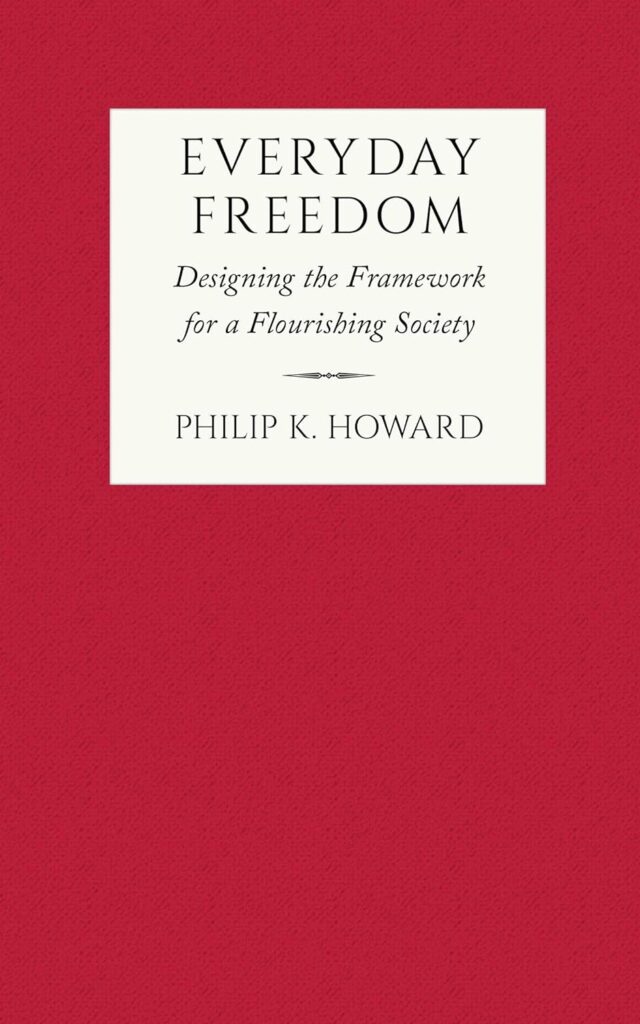

In his seventh and latest book, a slim volume called Everyday Freedom that was published last month, Howard makes what can only be called a startling admission coming from a longtime good government crusader — namely, that the American people today are facing a bigger problem than simply bureaucratic dysfunction. “I now see that the greater danger is not ineffective government,” Howard writes in the book’s preface, “but the corrosion of American culture. Alienation has become a plague: Many Americans no longer believe in America. That’s largely because, I argue here, they no longer have the freedom to take responsibility in their daily choices. Persistent failures feed the frustration and seed a culture of distrust. Instead of focusing on how to make things work, Americans obsess about what might go wrong.”

Howard makes what can only be called a startling admission coming from a longtime good government crusader — namely, that the American people today are facing a bigger problem than simply bureaucratic dysfunction.

According to Howard, this culture of alienation, frustration, and mistrust can be traced back to the 1960s — a decade, he argues, that was not just a time of great political and cultural upheaval, but a time that redefined for Americans what it means to be free. Before then, he writes, people enjoyed what he calls “everyday freedoms,” where they had “individual authority, at every level of society and every level of responsibility, to act as they feel appropriate, constrained only by the boundaries of law and by norms set by the employer or other institution.” In the 1960s, he contends, “freedom was reconceived as a concept of individual rights against anyone with authority” and “the framework of American law was largely rebuilt.” He further writes that the new framework included three mechanisms that were intended to protect average Americans from those who control the levers of power in our country. These mechanisms included:

– “Prescriptive rulebooks” that would dictate the “correct way” of doing things — “For forest rangers in national parks,” Howard writes, “volumes of detailed rules replaced the pamphlet that used to guide their activities. Safety in the workplace was regulated not by unsafe practices but by thousands of rules— many self-evident, trivial, or overbearing, such as requirements to illuminate stairwells, maintain neat closets, and use industrial grade hammers. Before the 1960s, there was no such thing as thousand-page rulebooks.”

– “Prescriptive rulebooks” that would dictate the “correct way” of doing things — “For forest rangers in national parks,” Howard writes, “volumes of detailed rules replaced the pamphlet that used to guide their activities. Safety in the workplace was regulated not by unsafe practices but by thousands of rules— many self-evident, trivial, or overbearing, such as requirements to illuminate stairwells, maintain neat closets, and use industrial grade hammers. Before the 1960s, there was no such thing as thousand-page rulebooks.”

– “Formal procedures” that were focused on process and forced officials to justify their decision-making — “These procedures soon took a life of their own,” Howard argues. “Giving a permit to modernize infrastructure, or disciplining a public employee, began to take years.”

– A “new litmus test of individual rights” that essentially encouraged and empowered people to sue — “Instead of being a protection against state power,” Howard writes, “these new rights let people invoke state power to address personal disappointments in the workplace or in schools. Almost any ordinary accident, say a fall on a playground, could be dressed up as an outrage with the benefit of hindsight. Why wasn’t there better supervision of the kids at the swing set?”

While these mechanisms were intended to protect Americans from those in positions of authority, Howard believes they also resulted in Americans — and especially those Americans who are in positions of authority — losing sight of the common good.

“I now see that the greater danger is not ineffective government, but the corrosion of American culture.” – Philip Howard

“Instead of a framework for human freedom,” he writes, “it’s an elaborate precautionary system aimed at precluding human error. Anything that goes wrong, any accident or disappointment, any disagreement, potentially requires a legal solution. Instead of charging officials to do what’s sensible, modern law presumes that the gravest risk is to leave room for the judgment of people in positions of authority. Who knows what evil might be done by a school principal, or environmental official, or supervisor? Instead of nurturing social trust, law after the 1960s infected society with distrust.”

So what’s the solution? For Howard, it begins with giving people in positions of authority the latitude to use their own good judgement. Here, he quotes James Madison, who wrote: “It is one of the most prominent features of the Constitution, a principle that pervades the whole system, that there should be the highest possible degree of responsibility in all the Executive officers thereof; anything, therefore, which tends to lessen this responsibility is contrary to its spirit and intention.” In Howard’s view, the thousand-page rulebooks and formal procedures which have been written and put in place since the 1960s run counter to the “spirit and intention” of which Madison writes.

Howard also holds up Pennsylvania Governor Josh Shapiro as a recent example of a public official who put his own judgement ahead of established procedure to address a crisis facing his state. The crisis occurred in June of last year, when a truck delivering 8,500 gallons of gasoline crashed beneath an elevated section of I-95 in Philadelphia. The explosion and resulting fire destroyed that section of highway, closing one of the most highly trafficked corridors in the Northeast. After experts said it would take months to make the necessary repairs, Shapiro stepped in and suspended all the rules and regulations that would get in the way of getting the section rebuilt. In large part because of this decision, the repairs were made in record time, and the highway reopened in 12 days.

Howard cites Operation Warp Speed as another example of person in a position of authority — in this case, President Donald Trump — putting his own judgement ahead of established rules and procedures. The result, of course, was that a Covid vaccine was developed in record time, saving millions of lives as a result.

It is these kinds of value judgements, as Howard calls them, that America must do more to encourage and restore. “The cure is not mainly new policies,” he writes, “but new legal operating structures that re-empower Americans in their everyday choices. People must have ‘everyday freedom,’ by which I mean the individual authority, at every level of society and every level of responsibility, to act as they feel appropriate, constrained only by the boundaries of law and by norms set by the employer or other institution. People must be free to draw on their skills, intuitions, and values when confronting daily challenges. They must own their actions. It is this ownership of choices that gives freedom its power and makes it the source of pride. That’s how things get done sensibly and fairly.”

Howard proposes scrapping the legal framework that emerged from the 1960s and replacing it with a new legal structure that: “replaces red tape and self-interested rights with individual responsibility and accountability. Instead of purging authority to prevent abuse, this framework rebuilds clear lines of authority to make common choices, to oversee those choices, and to define zones of protected freedom.” If there is a shortcoming in Howard’s book, it’s that this framework that he puts forward is rather broad. But the absence of his prescription should not take away from the accuracy of his prognosis.

Indeed, until we can move away from a system that favors rules and regulations over good judgement and common sense, we will continue to have a nation marked more by distrust and dysfunction than the everyday freedom which, Howard rightly argues, has made America great.

Lou Zickar serves as Editor of The Ripon Forum