The United States has mid-term elections coming up – and these days, that means the certain prospect of enormous volumes of misinformation and disinformation. But the virus-like spread of falsehoods doesn’t just plague political elections.

Today, misinformation and its malicious sibling, disinformation, permeate U.S. society so thoroughly that citizens have no way of knowing which information is accurate. Someone needs to clean up the information environment, or otherwise U.S. society will fragment as different groups believe different sources of information. The federal government can play a role as an impartial observer – but the most important role lies in educating and thus empowering citizens.

Early on in Russia’s war against Ukraine, reports emerged about cats trained by the Ukrainian armed forces to spot Russian snipers. One cat in particular, nicknamed the Tiger of Kharkiv, was said to be particularly skilled. Countless people kept sharing tales about the felines’ pursuits, and in no time the tales had traveled around the world. These stories proved to be false.

A couple of months later, an odd comment by a Reddit user, who claimed to once have visited Swedish friends and not been fed dinner at their house, went viral on Twitter, morphing into an avalanche of users who claimed that Swedes were racist. There has been no study that shows Swedes don’t feed their guests dinner – but that did not prevent the anger storm from spreading and causing reputational harm to the country.

Today, misinformation and its malicious sibling, disinformation, permeate U.S. society so thoroughly that citizens have no way of knowing which information is accurate.

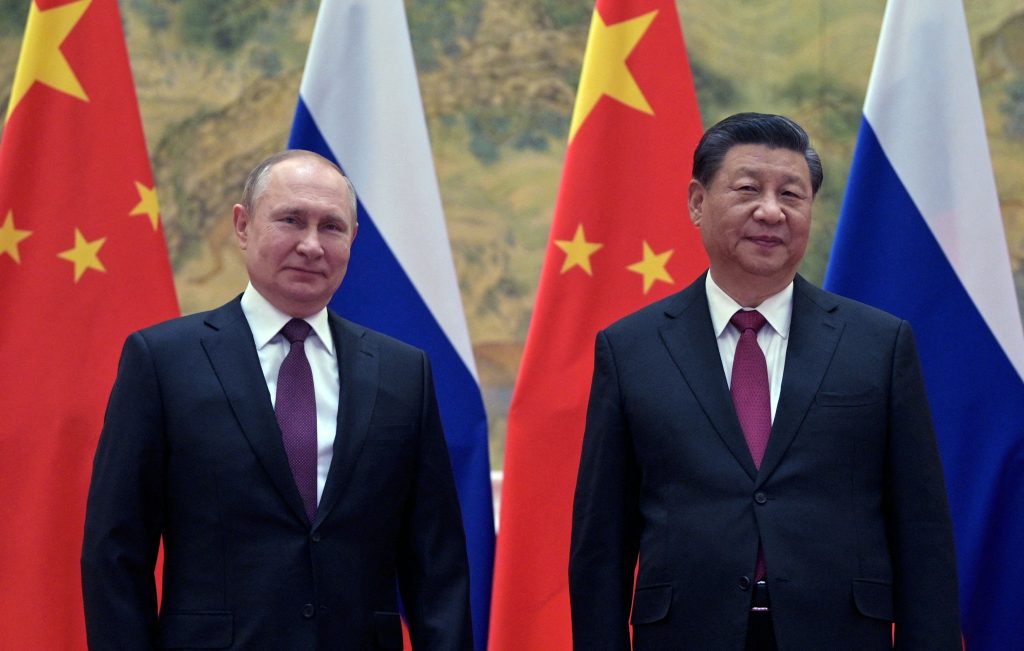

The so-called Swedengate also made other countries – and individuals – realize how vulnerable they are to campaigns against them based on misinformation (accidental falsehoods), disinformation (intentional falsehoods), or a combination of the two. And as Americans discovered in the 2016 election campaign, at the very least, geopolitical rivals are cunning in spreading falsehoods to weaken Western societies. In a recent iteration of such malign-influence campaigns, pro-Chinese agents have been trying to stir up protests against a new U.S. rare-earth processing company and planned rare-earth mines in the United States and Canada by posing as concerned local residents on social media. China dominates the world’s crucial rare-earth processing, using large volumes of imports from African mines.

Businesses, meanwhile, are already acutely aware of the power of misinformation and disinformation; indeed, some companies already harm competitors by using the “disinformation-as-a-service” packages offered by a host of shady outfits. PWC reports that disinformation-as-a-service providers charge “$15-$45 to create a 1,000-character article; $65 to contact a media source directly to spread material; $100 for 10 comments to post on a given article or news story; $350-$550 per month for social media marketing; and $1,500 for search engine optimization services to promote social media posts and articles over a 10- to 15-day period.” Such disinformation can cause real harm to companies, as negative news can prompt a share sell-off. Even if the share price subsequently recovers, recurring bouts of bad publicity can cause long-term harm to a company’s image and thus value. As a result, many businesses are now investing more money in the monitoring of news — but they clearly can’t prevent the creation and sharing of falsehoods.

Indeed, perhaps because most people think it doesn’t matter if they happen to see or read unverified information, the spread of misinformation and disinformation continues despite fast-increasing awareness of the harm they can cause. Citizen ineptitude is aided by commercial fake-engagement services that help falsehoods go viral. “Of the 114,061 fake engagements purchased, more than 96 percent remained online and active after four weeks. To date, none of the platforms’ actions have materially changed the functioning of the manipulation industry,” NATO’s Stratcom Center of Excellence notes in an April 2022 report.

Because public discourse based on falsehoods and inaccuracies risks making democracies ungovernable, tackling the falsehood-epidemic is imperative. Social-media companies, though, are wholly unwilling to fundamentally attack the problem – because falsehoods are 70 percent more likely to be shared on social networks, and social-media companies make their money on traffic. That means the epidemic has to be tackled as it is spreading. Yes, that means a role for the government – but mostly for citizens.

Because public discourse based on falsehoods and inaccuracies risks making democracies ungovernable, tackling the falsehood-epidemic is imperative.

The role the government should play is not the one envisioned for the Disinformation Governance Board launched by the U.S. Department of Homeland Security this spring. At the board’s launch, U.S. media reported that it would focus on issues as diverse as migration and Russia, but the board’s function and competencies remained unclear. By appointing a think tanker with expressed political leanings rather than a respected disinformation expert from the civil service, the government further undermined its own efforts. To nobody’s surprise, the board was swiftly suspended.

A much better idea would be for the U.S. Government to learn from Sweden’s new Psychological Defense Agency (MPF), whose very specific mission is to monitor and counter foreign malign-influence campaigns and build citizen resilience against misinformation and disinformation. That means that the MPF doesn’t insert itself into the domestic debate, but instead works to keep the country safe from external threats while helping citizens become more information-literate. Since its inception earlier this year, the MPF has, for example, identified an ISIS-linked disinformation campaign alleging that Swedish social services kidnap Muslim children and coordinated the government’s debunking of it. It has also launched the information-literacy website Bli inte lurad (“Don’t be fooled”).

Indeed, because governments of liberal democracies would enter treacherous waters if they tried to regulate the public discourse, any U.S. government intervention into the information flow has to be limited to falsehoods spread by foreign governments. The Global Engagement Center, a small unit within the State Department already tasked with countering foreign-led disinformation, could easily be expanded and given power to coordinate U.S. Government responses in the same manner as the MPF.

Because governments of liberal democracies would enter treacherous waters if they tried to regulate the public discourse, any U.S. government intervention into the information flow has to be limited to falsehoods spread by foreign governments.

U.S. states also have a role in stemming foreign disinformation. Connecticut is taking the lead. Hartford plans to appoint a civil servant to monitor and debunk disinformation about logistical aspects of state elections such as the location and opening hours of polling stations. The official will, however, not monitor or flag any falsehoods in the political debate. Colorado, meanwhile, is trying to teach its residents to be careful with what they share and encourages them, for example, to read a graphic novel on disinformation published by CISA. The Kansas City Library, in turn, teaches locals news and media literacy.

Such information-literacy education should complement the federal government’s monitoring of foreign disinformation. Citizens able to verify information will take the sting out of most misinformation and disinformation – but they need to be taught how. States can develop curricula and training materials that counties can use in their school systems and – to reach adults – in libraries. They can even offer it to employers.

Everyone has opinions, but nobody would want to consume falsehoods out of ignorance. Countering misinformation and disinformation involves not just the federal government but every part of society.

Elisabeth Braw is a senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute , where she focuses on defense against emerging national security challenges, such as hybrid and gray-zone threats. is the author of The Defender’s Dilemma: Identifying and Deterring Gray-Zone Aggression (AEI Press, 2022) and God’s Spies: The Stasi’s Cold War Espionage Campaign Inside the Church (Eerdmans, 2019).