Ronald Reagan changed the nation’s economic course during the first two years of his presidency, but the seeds of this achievement were rooted in a House member’s bold attempt to broaden Republican appeal at a time when Democrats held solid control of Congress.

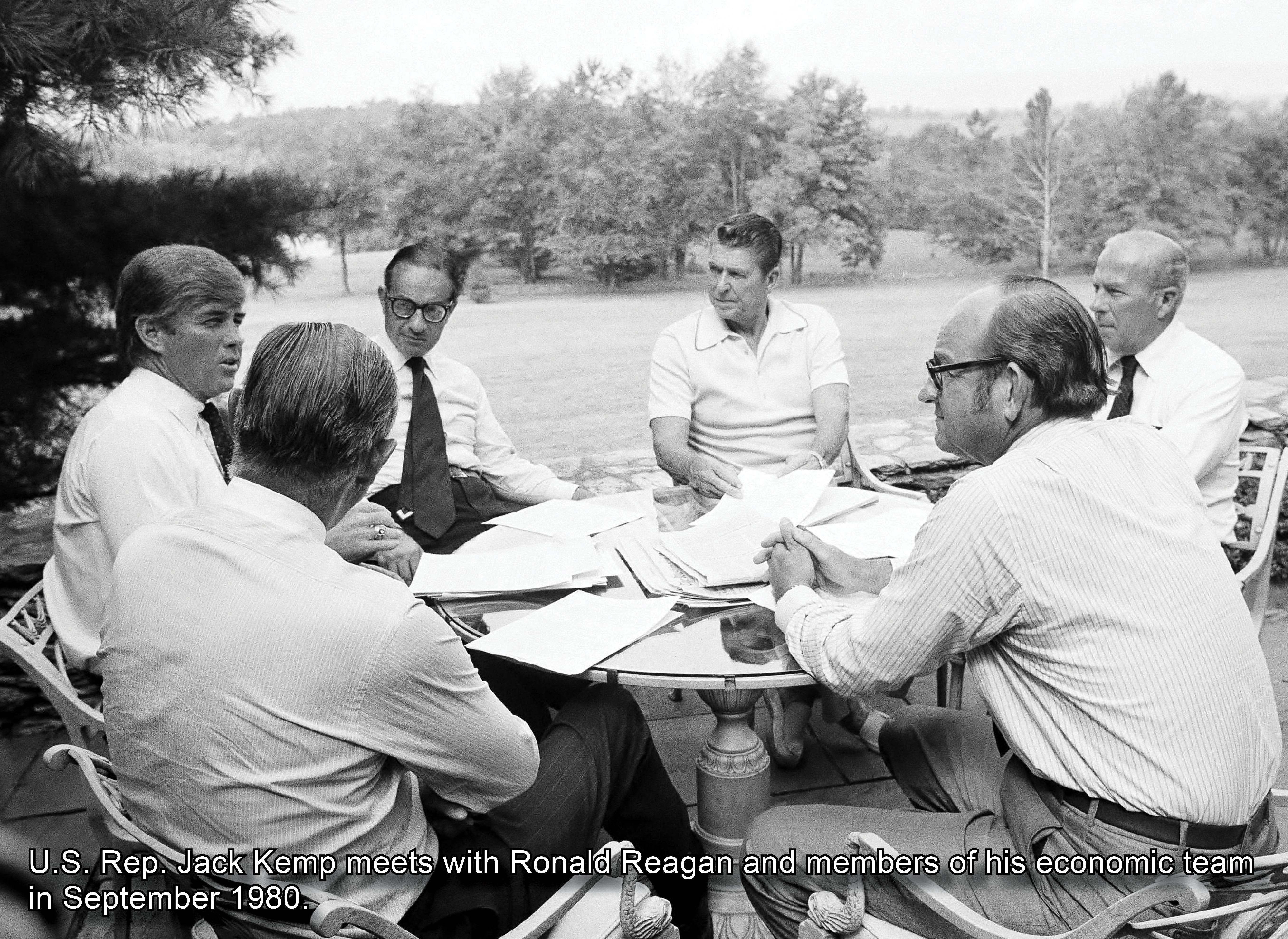

In 1977, Jack Kemp was a fourth-term member of the House from an industrial Buffalo, NY, district that had long been Democratic. Kemp, a quarterback with the Buffalo Bills before entering politics, was popular with blue-collar constituents, who otherwise tended to be suspicious of Republicans. Unemployed workers in hard-pressed Buffalo needed jobs, while businesses struggled to keep afloat. Kemp wanted a more uplifting message than austerity. He found it in the advocacies of political economist Jude Wanniski, an apostle of the emerging movement of supply-side economics. Wanniski convinced Kemp that substantial income tax cuts would spur lagging economic growth. Partnering with Sen. William Roth, a Delaware Republican, Kemp introduced a bill to reduce income taxes 10 percent a year for three years. It quickly became known as “Kemp-Roth.”

Supply-side economics envisioned a world stripped of tax preferences, economic regulations and subsidies that were strangling capitalism. Reagan, economically literate, did not at first embrace the supply-side argument—indeed, it can be argued that he never embraced all of it—but he was a thoughtful politician who wanted to attract working-class Democrats, as he had done when twice winning the governorship of California.

Ronald Reagan changed the nation’s economic course during the first two years of his presidency, but the seeds of this achievement were rooted in a House member’s bold attempt to broaden Republican appeal at a time when Democrats held solid control of Congress.

Reagan also knew that anti-tax fervor was on the rise, manifested in 1978 by voter approval in California of Proposition 13, a far-reaching tax limitation measure. Reagan was 68 years old that year and girding for a third try at the presidency. He had run uncertainly in 1968. But in 1976, he had demonstrated mass appeal when he almost snatched the nomination from Gerald R. Ford, a sitting president, over the solid opposition of the Republican establishment. Looking forward to 1980, many dismissed Reagan as too old or too ideological. But Reagan was optimistic both about his prospects and the future of the country, which was suffering from economic maladies and what President Jimmy Carter said was “a crisis of confidence…that strikes at the very heart and soul of our national will.”

Several of Reagan’s advisers were not thrilled by supply-side economics. They cautioned about deficits and worried that supply-siders might be overstating the impact of tax cuts on economic growth. George H.W. Bush, opposing Reagan for the presidential nomination in 1980, famously described the supply-side nostrum as “voodoo economics.”

Reagan was not deaf to these concerns, but he realized that Kemp-Roth offered to expand the economic pie, rather than just dividing it differently. He decided this might attract the working-class Democrats he prized. President John F. Kennedy had in 1963 proposed a tax cut to jump start a languishing economy. “A rising tide lifts all boats,” Kennedy often said. Reagan began quoting these words.

After winning the nomination and unifying the Republican Party by putting Bush on the ticket, Reagan defeated Carter in an electoral landslide with sufficient coattails to give Republicans control of the Senate. Democrats maintained a majority in the House, as they would throughout the Reagan presidency.

When Reagan took the oath of office on January 20, 1981, the United States was suffering double-digit inflation, with the Consumer Price Index registering 13.5 percent for 1980. The prime rate, the lowest rate for commercial borrowing, was 21 percent. Reagan’s first order of business as president was to propose the Economic Recovery Tax Act of 1981, much of which was based on Kemp-Roth.

Getting the bill through a House of Representatives controlled by the opposition wasn’t easy. Reagan was buoyed by an outpouring of public support after he showed wit and courage when wounded by a would-be assassin’s bullet on March 30. Still, it took another three months of persuasion and maneuvering to move the Reagan tax and budget bills through the House. Every Republican member voted for the Reagan program. Southern Democrats then known as Boll Weevils joined in support after Reagan promised he would not campaign against them in 1982 if they voted for both his tax and budget bills. The tax measure reduced income tax rates by 23 percent over three years and dropped the top marginal rate from 70 percent to 50 percent. It also cut corporate taxes and, in another borrowing from Kemp-Roth, indexed tax rates for inflation.

Nonetheless, recession arrived in July 1981. Reagan then turned to a traditional remedy espoused by Paul A. Volcker, the chairman of the Federal Reserve Board, who proposed to strangle inflation by reducing the money supply and forcing up interest rates. Volcker, a Wall Street banker, was a Democrat appointed by Carter, but to the surprise of many he and Reagan were on the same wave length. Carter had pressured Volcker to impose credit controls, which failed and were scrapped. Reagan told Volcker to do what he thought right. Volcker’s strategy worked at the cost of increased joblessness and plummeting approval ratings for the president. Reagan paid no heed. The worse the recession became the more he vowed to stay the course.

The recession ended too late to help Republicans in the 1982 midterm elections, in which the GOP lost 26 House seats. But this was relatively modest by historical standards, and Reagan shrugged off the losses. He had noticed the economy was improving. As it did, Reagan said wryly, “They don’t call it Reaganomics anymore.”

Kemp-Roth showed that a party out of power in the White House can lay down markers for what it will do if it regains executive control.

Ultimately, as Kemp observed, the combination of supply-side tax cuts and Volcker’s old-fashioned tight-money remedy achieved an enduring turnaround. The Reagan recovery that started in November 1982 lasted to July 1990, when Bush was in the White House. The economy grew a third. The stock market almost tripled in value. Nearly 20 million new jobs were created. The unemployment rate, 7.6 percent when Reagan took office and 9.7 percent at the height of the recession, dropped to 5.3 percent. The inflation rate was 13.5 percent when Reagan was elected and 4.8 percent when he left office—and continued to fall. It is a durable Reagan legacy, for annual inflation has never risen above 3.8 percent from 1992 to the present day.

Kemp-Roth, little more than a footnote to many present-day historians, had paved the way for this remarkable recovery. For one thing, it accustomed Congress to discussing tax cuts. For another, Kemp-Roth attracted crucial bipartisan support, notably from Sen. Bill Bradley, Democrat from New Jersey. Like Kemp, he was a former athlete, in Bradley’s case a basketball star with the New York Knicks. Like Kemp, Bradley believed that tax cuts would lead to economic growth.

Is Kemp-Roth a model for the present Congress? Perhaps. Kemp-Roth showed that a party out of power in the White House can lay down markers for what it will do if it regains executive control. Carter was as unpopular with Republican members of Congress as President Obama is today, but Kemp-Roth was not a slam at the president. Instead, it was a thrust into the future, a plan on which to build.

To be sure, partisan lines are more rigid now than they were in 1981. But voters still value leadership. They still want to know what a party stands for, not just who it is against. Kemp-Roth is a constructive example for Republicans–or indeed for any party out of power that seeks to regain the confidence of the American people.

Lou Cannon spent over 25 years covering Ronald Reagan as a reporter for the San Jose Mercury News and The Washington Post, and is the author of five books on the late President’s life.