Is the U.S. taxsystem rigged in favor of the rich? That’s the belief of many Americans today, but the data suggests otherwise. The U.S. tax and transfer system is highly progressive and redistributive. But if policymakers continue to double down on this progressivity while ignoring our nation’s debt, it could come at a cost to the American economy.

There are many ways to measure this, but the most thorough is the “effective fiscal incidence rate” — the amount of tax a person bears (directly and indirectly) relative to their comprehensive income (including government transfers). Government transfers — which include things like Social Security and Medicaid — make up 59 percent of the bottom quintile’s income; excluding transfers when looking at our tax code vastly understates the progressivity of our fiscal system.

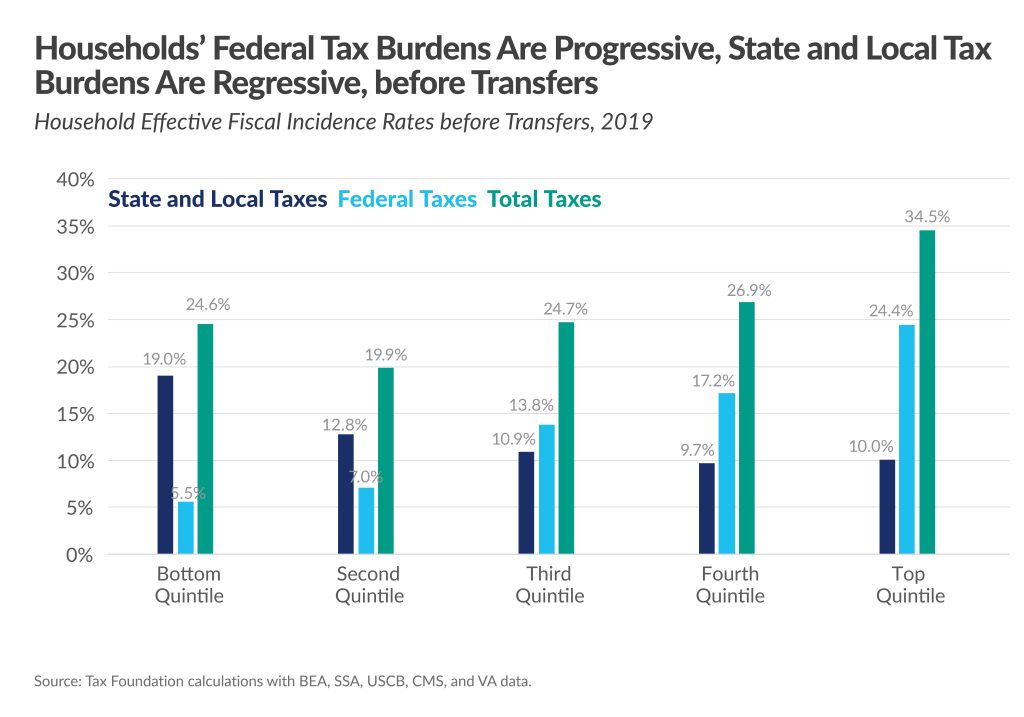

But even before accounting for government transfers, the combined federal, state, and local tax system is progressive. In 2019, the top quintile of households paid 34.5 percent, while the middle and bottom quintiles paid 24.7 percent and 24.6 percent, respectively.

In 2019, the top quintile of households paid 34.5 percent, while the middle and bottom quintiles paid 24.7 percent and 24.6 percent, respectively.

When transfers are included, the system becomes substantially more progressive: the top quintile’s rate jumps to 41.4 percent, while the middle and bottom quintiles drop to 22.4 percent and 10.1 percent, respectively. All told, the transfer system redistributed $1.7 trillion from the top two quintiles to the bottom three in 2019. This is not a system that benefits the rich at the expense of the poor.

While this sounds “fair” on paper, keep in mind that progressivity comes at a cost. Research finds a negative relationship between taxes and growth, with a more pronounced effect for progressive taxes.

Why? Because people respond to incentives. On the margin, higher taxes on corporations and shareholders reduce the incentives to invest, which means fewer workers, lower wages, and less innovation. And progressive taxes lower the returns to education, investment, entrepreneurialism, and risk-taking. Lower levels of these activities harm not just individuals, but the broader economy.

Unfortunately, this hasn’t tempered proposals to make the U.S. tax system even more progressive. At the state level, seven states have introduced legislation to enact wealth taxes targeting net worth, capital gains, and estates. These, as Tax Foundation’s Jared Walczak puts it, “are economically destructive, their base is almost impossible to measure accurately, and they create perverse incentives and promote costly avoidance strategies. Very few taxpayers would remit wealth taxes — but many more would pay the price.”

And at the federal level, President Biden’s recently released budget would add almost $4.8 trillion in new taxes over the next decade, targeted at high-income individuals and businesses. Though these policies are aimed at the rich, they’ll impact everybody. These changes would reduce long-run GDP, shrink wages, and eliminate 335,000 jobs, according to Tax Foundation research.

President Biden’s recently released budget would add almost $4.8 trillion in new taxes over the next decade, targeted at high-income individuals and businesses … These changes would reduce long-run GDP, shrink wages, and eliminate 335,000 jobs.

But just as bad tax policy can hurt the economy, the tax system can be a lever policymakers can use to boost investment, create better jobs, raise incomes, and improve standards of living.

Take the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA), which overhauled the federal tax code with pro-growth reforms. It significantly lowered average individual income tax rates for all income groups and decreased the cost of capital for businesses. This was a step in the right direction.

The problem: some of TCJA’s policies are temporary. The individual income tax provisions will sunset at the end of 2025, and important business policies — like 100 percent bonus depreciation — are already phasing out.

If TCJA’s temporary provisions expire, so will the economic benefits they produce; they need time to maximize their growth-inducing potential. For example, in 2018 the Tax Foundation estimated that if the individual income tax provisions are extended, long-run GDP would increase by 2.2 percent, long-run wages would rise by .9 percent, and 1.5 million jobs would be added. And in 2022, we estimated that making 100 percent bonus depreciation permanent would increase long-run GDP, bump long-run wages, and add tens of thousands of jobs.

Making these TCJA provisions permanent would have significant benefits, but these too come with a trade-off: less government revenue and larger federal deficits. While a bigger, more prosperous economy would generate more revenue and partially offset the initial deficit increase, there would still be a shortfall.

The crux of the issue, however, is not revenue; it’s spending.

This year, revenue as a percentage of GDP exceeded its 50-year average by .9 percentage points. But it didn’t make a dent because spending also exceeded its 50-year average — by 3.6 percentage points. Spending growth, driven mostly by entitlements and interest on the debt, will continue to outpace revenue growth over the next decade unless something changes.

We can’t tax our way out of this problem, but prioritizing growth over progressivity gives us a better chance. Making responsible spending reforms and pursuing pro-growth tax policies will put us on the path to fiscal sustainability.

Daniel Bunn is president and CEO of the Tax Foundation, a think tank in Washington, D.C.