There’s a mixed bag of actions being taken by the Secretaries of State and election officials in states across the country in order to mitigate the infiltration of election systems during the 2018 mid-terms. Some prioritize new voting machines, others seek to bolster their cybersecurity, and others seek to improve the training and communication of state and local election officials. But not only are there vastly different approaches to election security, there are varying levels of concern from one state to another.

The intelligence community in the United States has been forthcoming with their findings of foreign meddling in the 2016 election. Agencies have published reports, top officials went to Capitol Hill to testify and give closed-door briefings to Members of Congress, and state election officials have been notified of previous and ongoing cyberattacks. Despite the unanimity of alarm among federal agencies of impending cyber incidents, state responses to the issue are far from consistent.

Traditionally, states have been apprehensive to the notion of the federal government intervening with their constitutionally reserved right to run elections as they see fit—one example being the 15 Republican and Democratic states denying President Trump’s voter fraud commission’s request for detailed voter data last year. With this in mind, it is no surprise that states are reluctant to accept offers from federal agencies to assist them with handling their election systems.

Despite the unanimity of alarm among federal agencies of impending cyber incidents, state responses to the issue are far from consistent.

So, what are states doing in advance of the upcoming election? This question less than a year ago would have been a tough one to answer. In early months of 2018 only a fraction of states released press releases addressing their election security, and an even smaller portion published a plan outlining actions being taken to actively prevent future attacks.

It wasn’t until this past March—when $380 million was appropriated to the U.S. Election Assistance Commission (EAC) for the sole purpose of funding election security enhancement grants—that Secretaries of State and Boards of Elections across the country started looking into the threat seriously. Even then, that $380 million is only a fraction of what some lawmakers wanted to see allocated, and experts argue that updating the most outdated voting machines alone would cost $500 million.

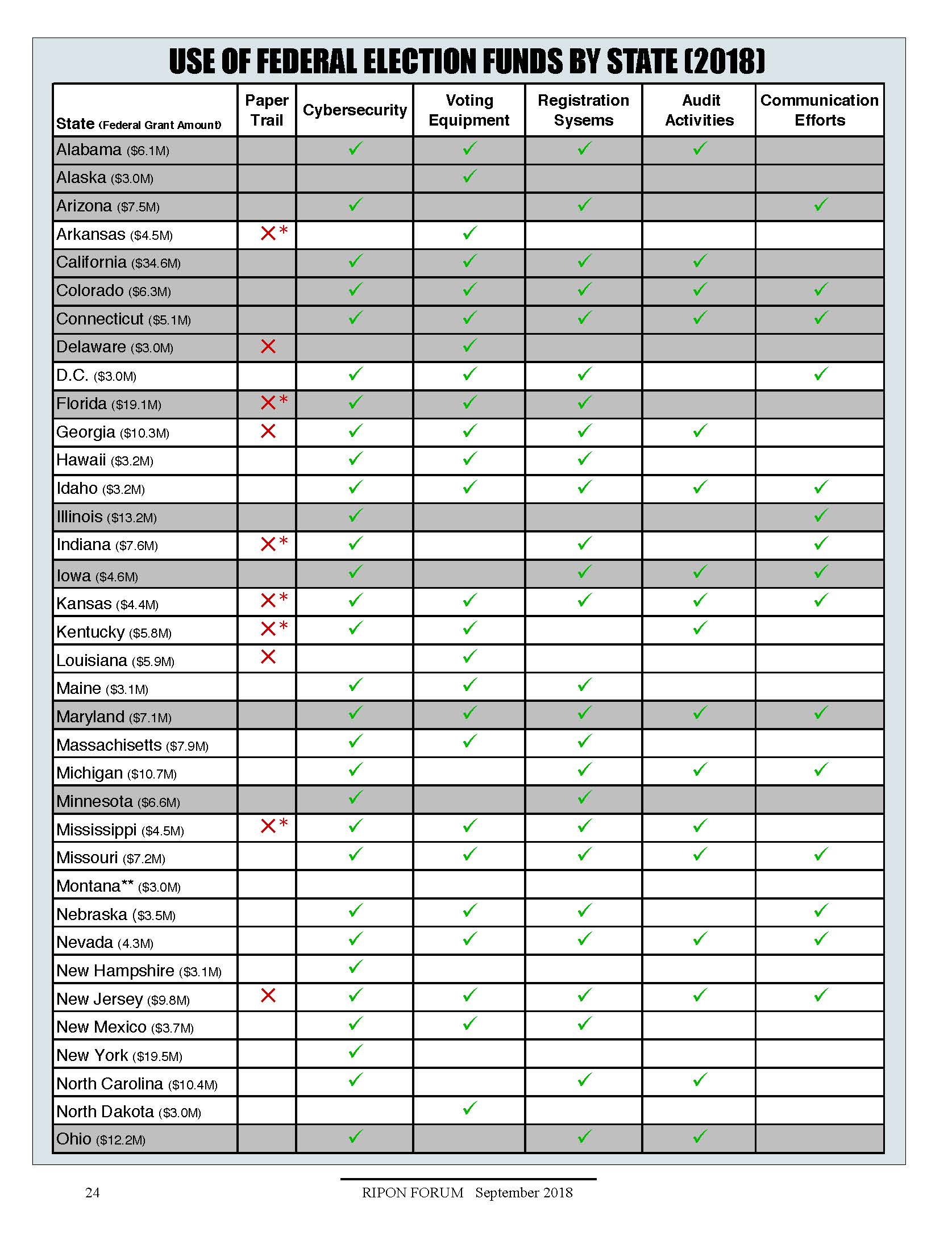

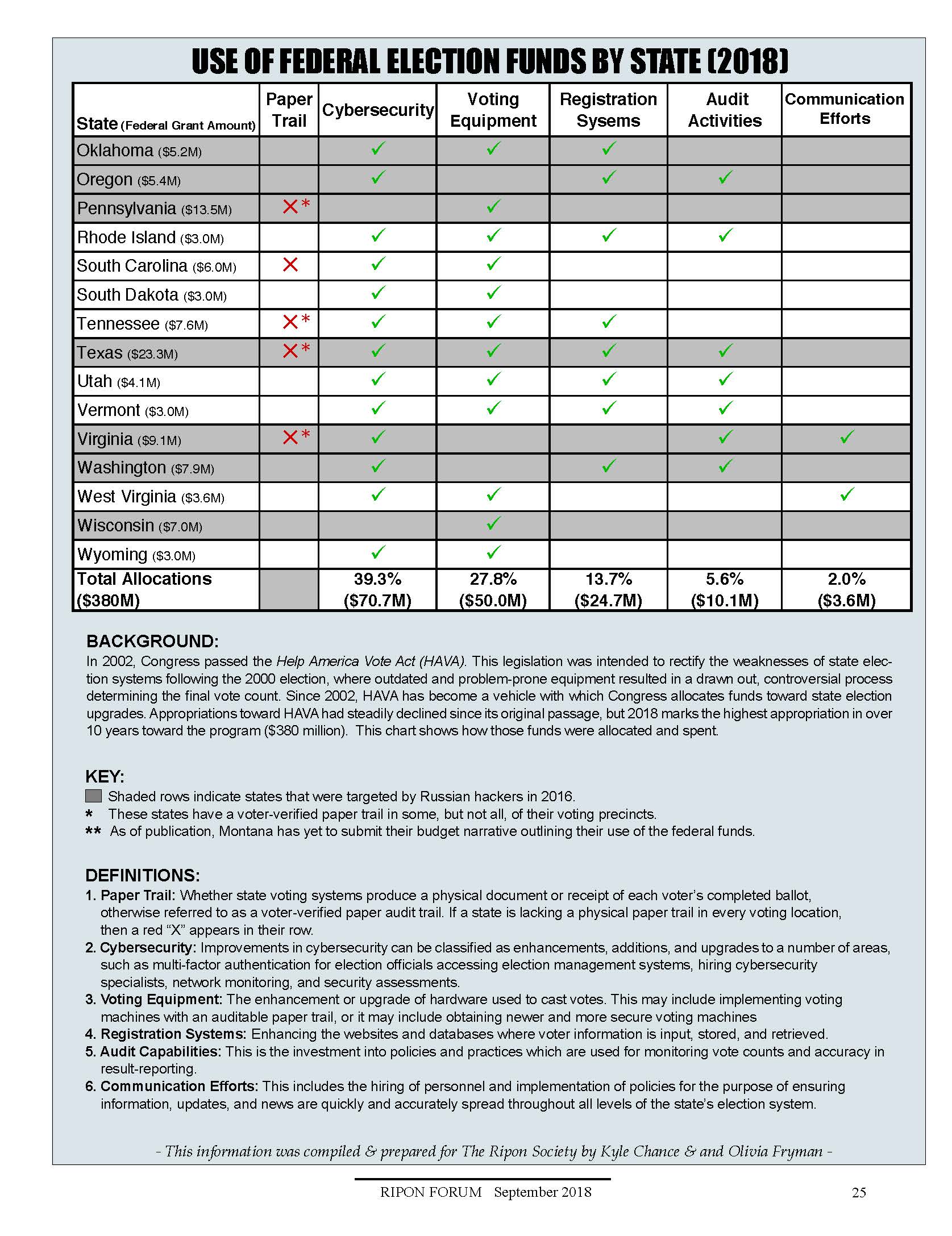

In order to be eligible for their share of these federal grants, each state was required to create a budget narrative outlining how they would use the funds to make improvements that met EAC standards. According to the EAC, there were five major categories that for which states are planning to use the grant funding: cybersecurity, new voting equipment, improved voter registration systems, post-election audit activities, and improved election-related communication efforts. Two thirds of all funds will be allocated toward programs targeting the first two categories of cybersecurity and voting equipment.

Other efforts identified by the state officials include training for state and local election officials, hiring of personnel specialized in cybersecurity or information technology, and drafting internal policies outlining new security protocols and incident response plans.

The progress over the past six months is laudable, to be sure, but it still may not be enough. Bolstering security through rebuilding databases, replacement of election equipment, and the implementation of new cyber strategies will not simply happen overnight. After looking through each state’s budget narrative, it is apparent that this endeavor of overhauling our election is being approached by states as a long-term undertaking with some security measures not being fully in place for nearly six more years.

Some goals will be achieved ahead of the 2018 mid-terms, such as personnel training and tweaks to digital systems. But, the most notable changes (new and upgraded equipment, more secure voter registration systems, and being able to audit election results) will not see completion until after the 2018, 2020, and even the 2022 elections. Logistical complications, contractual obligations, and a lack of resources help explain the range of timelines.

The most notable changes (new and upgraded equipment, more secure voter registration systems, and being able to audit election results) will not see completion until after the 2018, 2020, and even the 2022 elections.

West Virginia, for example, has a budget narrative where they outline to the EAC their use of $3.6 million of grant funding. Secretary of State Mac Warner admitted, “West Virginia’s economic situation since the first round of [federal grants] in 2002 has deteriorated and many less-populated counties simply do not have resources to prioritize funding election systems over debts that continue to rise, such as jail bills and road maintenance,” he continued, “Funds to acquire [EAC] mandated machines that come with the latest and greatest technology and protections simply do not exist in many counties.”

Last year, the U.S intelligence community announced evidence of Russian infiltration and scanning of the election systems in 21 states. But, clandestine activities may stretch much further than originally reported according to Chris Krebs, the Undersecretary of DHS’ National Protection and Programs Directorate. “I would suspect that the Russians scanned all 50 states,” Krebs said in his testimony during a Congressional hearing in July. He further explained that these 21 states, which have been found to be targets of Russian cyber activity, are only the one’s that they know about.

As for the states which have been confirmed as being scanned by Russia, their reaction to the information has been all over the place. The state of Washington, for example, is reevaluating their election system, prioritizing system assessment and penetration testing in order to prevent future break-ins. The state has also partnered with DHS to assess vulnerabilities, share information, and receive in-person cyber support. Actions like these lay the groundwork for a properly prepared system, supported fully by officials and policymakers from the top down.

Florida, on the other hand, is implementing policies seen as counterproductive according to local election officials. Despite the state receiving the second largest sum of nearly $10 million in federal funds, many counties are complaining. They accuse the state of implementing arbitrary and counterintuitive rules for how the money is being distributed, which include quick deadlines and provisions stating that all money not spent this year must be yielded back to the state. The problem with these policies is that they encourage the counties to act with short-term thinking, and it hinders their ability to adequately plan a long-term investment strategy for their election security.

Rebuilding America’s electoral infrastructure is no small task. It will take time, resources, and an unprecedented level of cooperation in order to properly prepare to fend off international attacks to undermine U.S. elections. The mid-terms are just weeks away, and states across the country will soon find out whether they did enough in time to safeguard the credibility and security of their elections.

Kyle Chance is the Ripon Forum’s Editorial Assistant. For a chart illustrating how each state is spending federal election funds, please see below.