When Dwight D. Eisenhower became president in January 1953, there had not been a Republican president since President Herbert Hoover left office in 1933.

Coincidentally, Russell Kirk published The Conservative Mind in 1952, and because of the election of Eisenhower it became a best-seller. The Eisenhower presidency was “transformative,” as the Reagan presidency was, and as the Obama presidency probably will be today.

The New Deal coalition had held even in 1948 when President Harry S. Truman defeated Republican Thomas Dewey despite the Progressive party candidacy of former Vice President Henry Wallace and the States Right party of Sen. Strom Thurmond. The election of Eisenhower opened the way for a Republican resurgence. In effect, the Republican Party had to be reinvented. Today, the Republican Party will similarly have to be reinvented.

Though we did not know why in January 1953, we did know that the fighting in Korea soon ceased, though negotiations continued at Panmunjom. In fact, there never was an official Korean peace treaty. One of Eisenhower’s earliest moves ended the fighting, and signaled the kind of President Eisenhower would be: tough, realistic and successful.

Eisenhower had “gone to Korea,” as he had promised during the 1952 campaign. He inspected the front lines there and had seen that the North Korean-Chinese defenses in depth would be difficult and very costly to penetrate. President Eisenhower therefore sent a secret message to Mao Zedong through New Delhi saying that unless the fighting stopped we would respond “without inhibition” as to the weapons we would use. In other words, the nuclear option was on the table.

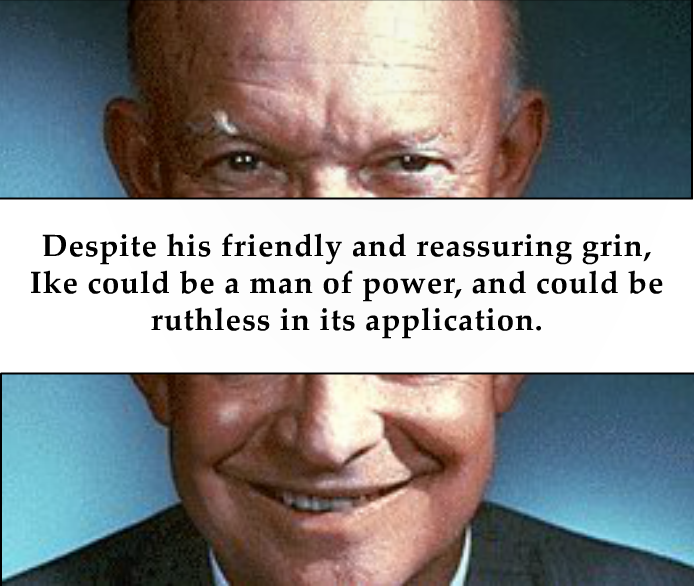

Despite his friendly and reassuring grin, Ike could be a man of power, and could be ruthless in its application. His sometimes garbled syntax was a mask to conceal his actual intentions. In fact, he was precise and lucid in conference and in writing. (The book to read on this is Fred I. Greenstein’s The Hidden Hand Presidency). Eisenhower was also a superb administrator.

I have two personal anecdotes that will illustrate this.

During the middle 1950s, I was an officer in Naval Intelligence, assigned to the Boston office in the First Naval District. We had a number of responsibilities, including, for example, background investigations for people needing security clearances. One day – it must have been in 1955 – my commanding officer came into my office where I was sitting behind my desk. He looked pale. He said, “Eisenhower was just on the phone.” He did not tell me why, but I was impressed. Eisenhower had not asked his chief of staff to call the Intelligence office. He had not passed whatever problem there was to the Secretary of the Navy. Eisenhower had picked up his phone and said, “Get me the First Naval District Intelligence Office.”

Along similar lines, a couple of years ago I had lunch in Hanover with Paul Staley who had been in my class (1951) at Dartmouth. He had been captain of the football team, and after Dartmouth had gone to the Harvard Business School. While there he met and married Joan Killian, daughter of James Killian, president of MIT. Staley told me that in 1957 when the Soviet space vehicle was circling the earth and emitting its beep-beep-beep signal, President Killian’s phone rang in his office at MIT. It was Eisenhower. He said, “You are the best one in the country to tell me what this is and what it means. I want to see you ere at nine o’clock tomorrow morning.”

These two anecdotes illustrate Eisenhower’s basic approach to governing and leadership. He was fact-based, decisive and direct. In domestic policy, he was a center-right Republican, who understood that the best features of the New Deal could not be repealed, and unlike his Republican rival, Ohio Senator Robert Taft, knew that isolationism was not viable. His accomplishments included the advance of the nuclear powered navy and the development of the Polaris missile, which could be launched by a submarine without surfacing and against which the Soviets had no defense. He also began the aerial surveillance of the Soviet Union with the sub-stratospheric U-2 spy plane. During the subsequent Kennedy Administration, the U-2s discovered the missiles Khrushchev was deploying in Cuba. President Eisenhower also produced three budget surpluses and began the interstate highway system.

That’s not to say his administration was without error. One of the most significant mistakes he made, and perhaps one of the most critical lost opportunities for America in the 20th century, involved Iran. In 1951, Iran elected Mohammed Mossedegh prime minister. He was the last democratically elected leader of Iran. Though the Cold War had polarized many nations, Mossedegh declined alignment. Mossedegh nationalized the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company, a British monopoly of Iranian oil. In response Britain imposed a world-wide embargo of Iranian oil and banned the export of goods to Iran while taking its case to the international Court of Justice at The Hague. The Court found that Iran had done nothing illegal. Yet the United States continued to support the British embargo. The United States was also concerned about the possible influence of the Tudeh (Communist) party in Iran.

In domestic policy, he was a center-right Republican, who .. also produced three budget surpluses and began the interstate highway system.

In 1953, on orders from President Eisenhower, the C.I.A. organized a military coup that overthrew the Iranian government. Mossedegh was imprisoned and soon placed under house arrest for life. Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi, supported by the United States, became the ruler of Iran for the next 25 years with the assistance of the brutal and effective secret police SAVAK, which crushed all opposition. The Shah denationalized the Iranian oil industry and aligned Iran with the West in the Cold War. President Nixon later praised the Shah as a force for stability in the region. Yet in 1979, a revolution overthrew the Shah, bringing to power hard-line Islamists led by the Ayatollah Khomeini. The ensuing hostage crisis in Teheran discredited the Carter administration. It also paved the way for Iran to become a force of instability in the Middle East.

This error aside, Eisenhower remains, to me, a near-great Republican president. In most things, he was fact-based, prudential, and essentially conservative. His Presidency and his approach offer an excellent paradigm for a reformed Republican party today. But getting there will not be easy. If a large majority of Republicans try to reform the party in a common sense direction with Eisenhower as the paradigm, a third party could very well be the result.

But Truman won in 1948 despite two breakaway parties, and a common sense Republican party would be the core of a new majority – a majority that would not only win local races and races for the Senate and the House of Representatives, but one that would be waiting for the Democrats to make major mistakes, as in time they surely will.

Jeffrey Hart is professor emeritus of English at Dartmouth College. He wrote for the National Review for more than three decades, and also served as a speechwriter for both Ronald Reagan when he was governor and for Richard Nixon.