America faces a crisis of income insecurity — a crisis that providing people with a Universal Basic Income stands to solve.

Despite the frequently heard claim that the federal government spends a trillion dollars on social welfare, less than a quarter of that resembles anything close to income support for the poor or distressed, and is less than what we spend annually subsidizing employer based health insurance.

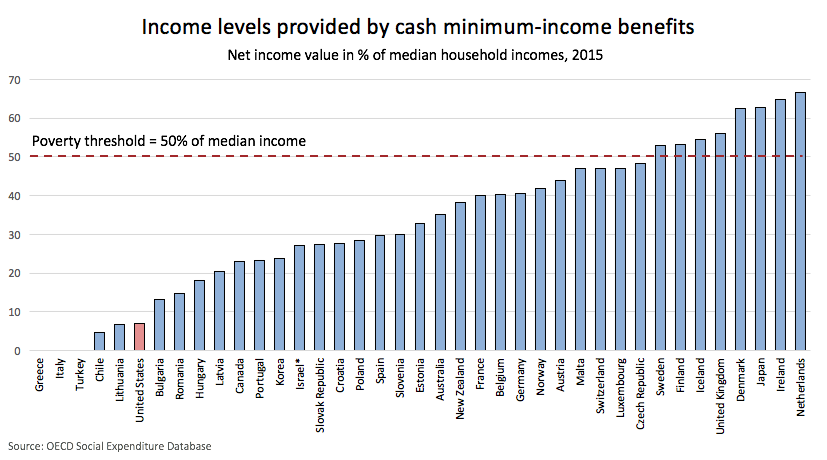

Look instead at the OECD’s measure of net income supports, a measure of a country’s de facto “minimum income” across developed nations, which reveals that the U.S. welfare system is among the stingiest in the developed world. For a country that prides itself on its economic dynamism, the massive UBI-shaped hole in our safety-net comes with steep costs.

Take China’s entry into the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2001. Chinese imports benefited millions of Americans through lower consumer prices. At the same time, Chinese import competition destroyed nearly two million jobs in manufacturing and associated services — a classic case of “creative destruction.” Yet rather than help those workers adjust, our social insurance system promoted languishment.

Despite the frequently heard claim that the federal government spends a trillion dollars on social welfare, less than a quarter of that resembles anything close to income support for the poor or distressed.

In the regions of the United States most exposed to import competition, Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) was more than twice as responsive as unemployment insurance and Trade Adjustment Assistance (TAA) combined, despite being one of the most restrictive disability programs in the developed world. The “China Shock,” as it’s come to be known, fueled a subsequent growth in anti-trade and nativist sentiment that contributed directly to political polarization and support for populist politicians.

Who could be surprised? Displaced workers become justifiably angry in the absence of robust income supports. In a democratic society, this means that even one-off economic shocks will often have lasting political and economic consequences. In contrast, the economic security provided by a UBI would promote risk-taking and entrepreneurship in the here and now, while ensuring that the creative destruction brought on by automation and artificial intelligence in the years ahead avoids generating popular backlashes of their own.

Critics of UBI will argue that income for nothing undermines the incentive to work, but rarely do they back-up their claims with evidence. Studies of UBI-like schemes — from Canada’s generous child allowance to the annual oil dividend provided to Alaskan residents by their Permanent Fund — all suggest that the work disincentives of “no-strings attached” cash transfers are negligible. Indeed, in many cases the principles behind UBI quite clearly promote work. The United Kingdom, for instance, recently reformed its core disability program, the Personal Independence Payment (PIP) , with the principles of UBI in mind. Unlike SSDI, which restricts the ability of claimants to work, the new UK system is universal and unconditional, meaning that those who are assessed for recurring disability benefits are not penalized for re-entering the labor force if and when their condition improves. Similarly, Finland is currently experimenting with UBI as a replacement for unemployment insurance, again in order to encourage greater work.

The economic security provided by a UBI would promote risk-taking and entrepreneurship, while ensuring that the creative destruction brought on by automation and artificial intelligence in the years ahead avoids generating popular backlashes of their own.

The cost of a UBI would obviously depend on its design and implementation. While some envision providing every man, woman and child $10,000 a year at an annual cost of over $3 trillion, others propose a smaller minimum income that gradually phases out with earnings. Known as a negative income tax (NIT), its budgetary cost would be an order of magnitude less than a full UBI, but would have a similar role in reducing income insecurity. Another approach would be to follow Denmark’s lead and combine generous wage replacements for laid-off workers with strong supports for re-employment. While not technically a UBI, their supercharged employment insurance system is nonetheless one way to provide robust income security for workers displaced by trade and automation.

Whatever option policymakers choose, it’s clear that the status quo is unsustainable. Until we begin to take America’s income insecurity crisis seriously, our economy will remain hyper-vulnerable to economic disruptions and the reactionary politics that invariably follow suit.

Samuel Hammond is a Poverty and Welfare Policy Analyst for the Niskanen Center.