“I saw a sign advertised recently with a remarkable quotation: “85% of statistics on the Internet are made up.” — Abraham Lincoln.

We can joke about statistics, and sometimes it’s funny. But when we’re counting lives that may be diminished by prenatal exposure to potentially harmful substances — the numbers really matter. And when we’re talking about the tragedy of a child who has been removed from her birth family and placed in foster care, we need to do all we can to get the numbers right to make sure that practice and policy are helping families.

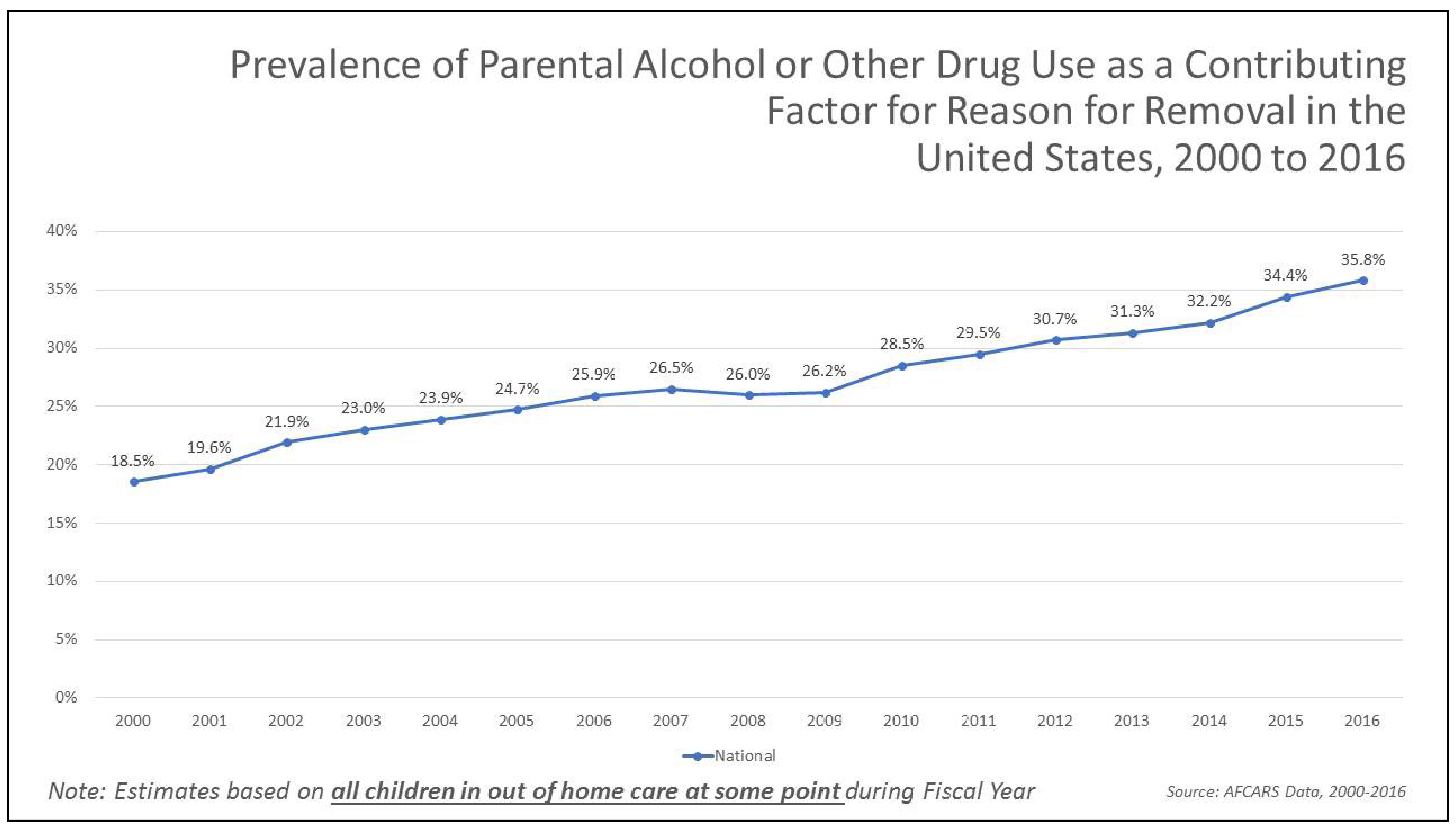

The impetus for this essay included a request to comment on the “highest rate of parental drug use in 30 years among child welfare cases.” Indeed, the data look bad. Over the past 15 years, reports by states to the federal government regarding parents whose alcohol or drug use resulted in a child’s placement into protective custody have steadily increased — from 18.5% in 2000 to 35.3% in 2016.1

Over the past 15 years, reports by states regarding parents whose alcohol or drug use resulted in a child’s placement into protective custody have steadily increased — from 18.5% in 2000 to 35.3% in 2016.

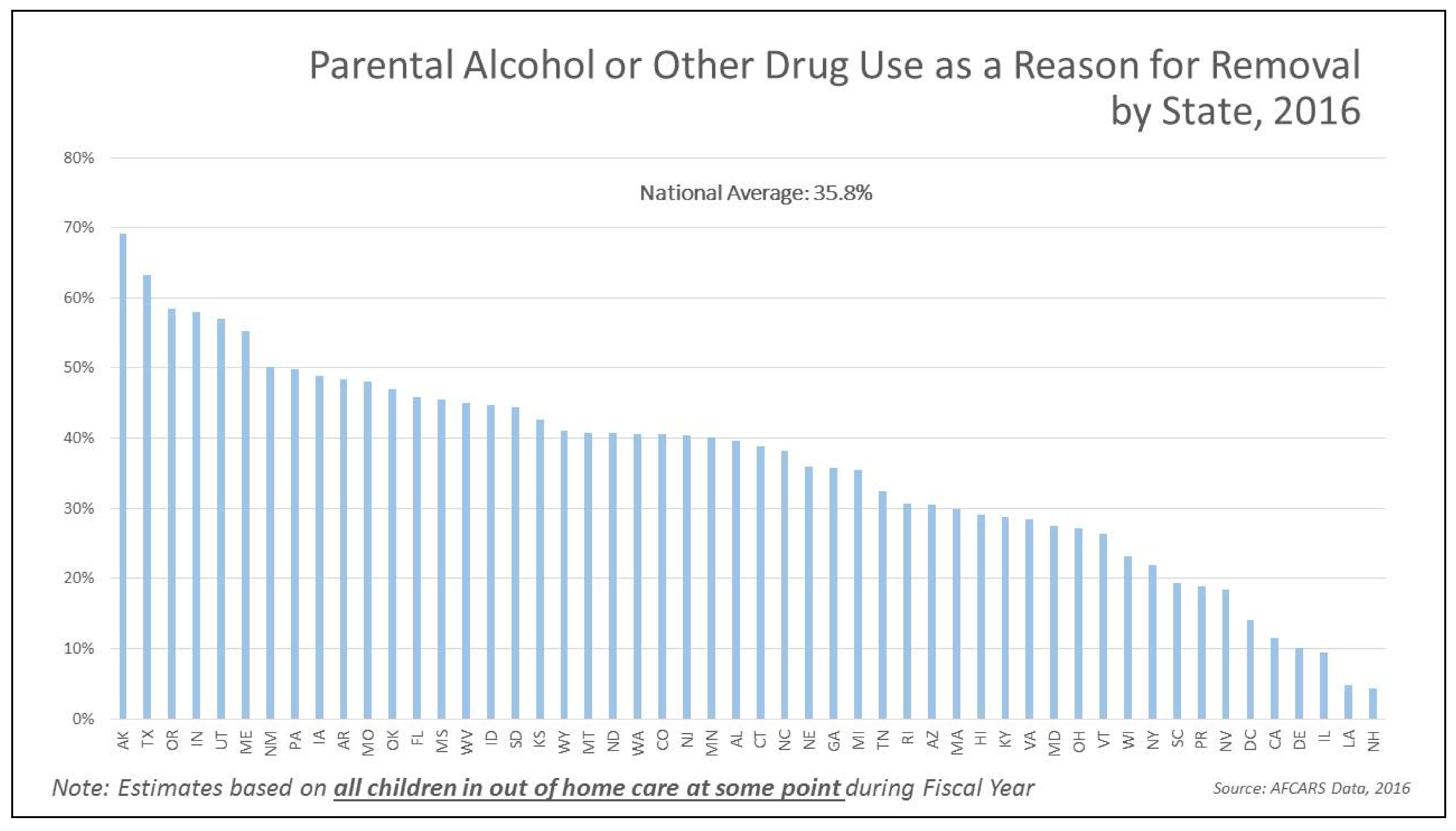

However, states report wide variation in these data from less than 10% to nearly 70%. The states reporting higher rates have typically made two important changes – namely, they have improved their screening protocols and their information system to count these .

Another disturbing trend is the increasing number of infants placed in out-of-home care.

Children under the age of one make up an increasing percentage of child placements — from 13.4% in 2000 to 18% in 2016 — with nearly 50,000 babies removed from their birth parents, more than twice as many as any other age group in 2016. Forty two percent of children in care are under the age of five.

We don’t have data to know if those 50,000 babies and young children are associated with prenatal substance exposure. An estimated 220,000 of all births are annually exposed to illicit drugs, 352,000 exposed to alcohol, and 34,000 of those exposed to heavy drinking — despite warning labels on every alcohol bottle sold. In addition, 488,000 are exposed to tobacco despite its known association with poor birth outcomes. A much smaller but still significant number of babies are identified as experiencing neonatal withdrawal symptoms from opioids— an estimated 24,000 each year.

Children under the age of one make up an increasing percentage of child placements — from 13.4% in 2000 to 18% in 2016 — with nearly 50,000 babies removed from their birth parents.

Children under the age of one make up an increasing percentage of child placements — from 13.4% in 2000 to 18% in 2016 — with nearly 50,000 babies removed from their birth parents.

Over the past half century, the country has witnessed several drug epidemics — the heroin epidemic of the 1960s and 70s, cocaine in the 80s, methamphetamine in the 90s and 2000s, and now prescription drugs and other opioids in the 2010s. In each of these epidemics, we’ve seen babies on covers of weekly magazines. They are the innocent victims of the latest drug scourge. Yet the resulting policy action is too often sporadic, resulting in short-term grant programs aimed at improving conditions in some communities. But, overall, policies have failed to support families by preventing substance use disorders and associated child neglect. This scattered approach without an effective long-term policy strategy has not been adequate to meet the needs of these young children and their families at the scale of the problem, rather than small projects.

Childhood trauma is also under-emphasized, as it affects substance use disorders. A 2003 study found that, compared to persons without childhood trauma experiences, individuals with five or more adverse experiences — such as parents with a substance use disorder, divorce, or incarceration — were seven to ten times more likely to have illicit drug use problems, and twice as likely to be alcoholic. Women, in particular, are often coping with the combined effects of their own early experiences of trauma, including childhood sexual abuse, as the #MeToo movement has recently underscored. Unless our policy and practice respond to this trauma, we are perpetuating an intergenerational cycle of trauma and substance abuse.

So what can be done to build a more effective strategy to improve the data and policy responses?

- Conduct universal screening for substance use during pregnancy. Screenings with a response that supports women’s abstinence and treatment interventions are critical. However, these interventions must be non-punitive and connect expectant mothers to supportive treatment services that meet their unique needs. Creating fear of negative repercussions among pregnant women who need help too often suppresses their engagement in prenatal care and treatment services. Punishing mothers and not providing a connection to the treatment they need isn’t an appropriate policy response for the infants we seek to protect.

- Fix the data systems. Universal screening, clarity in data systems, and requiring states to submit these data would go a long way in turning the tide of opioids’ effects on children and families today, while preventing another child protection caseload explosion in the next substance use epidemic.

- Prevent prenatal exposure to substances. While the campaigns to decrease tobacco and alcohol use during pregnancy have not achieved universal compliance, current levels of use are much less than in my generation of baby boomers. Then, mothers didn’t know as much about the dangers of tobacco use and were often encouraged to “have a nice glass of wine” while they were pregnant. The effect of these more recent social taboos have been dramatic for today’s young mothers and good for their babies.

- Implement infant and caregiver plans of safe care. As required by the Child Abuse Prevention and Treatment Act since 2003, each Governor has been asked to assure that their state has policies and programs for healthcare providers to notify child protective services when a baby has been prenatally exposed and, to respond with a plan of safe care. In 2016, Congress made it clear that this plan must address the needs of the infant and his/her family or caregiver. But those systems are not yet in place in most states.

It’s past time to move these infants from the covers of magazines and into a policy response that prevents child abuse and neglect and promotes family recovery.

Nancy K. Young, Ph.D., serves as Executive Director of Children and Family Futures, a national nonprofit organization based in Lake Forest, California that focuses on the intersections among child welfare, mental health, substance use disorder treatment, and court systems.

__________________________________________________________

[1] Children and Family Futures (2018). Analyses of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Administration on Children, Youth and Families, Children’s Bureau. 2017. Adoption and foster care analysis and reporting system (AFCARS) Foster Care File FY 2016. Ithaca, NY: National Data Archive on Child Abuse and Neglect [distributor]. https://ndacan.cornell.edu