Elected leaders profess to be concerned about the nation’s long-term economic growth. You’d never know it, however, by looking at the federal budget.

For one thing, the budget suffers from a growing structural gap between spending and revenues. Under current law, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projects that annual budget deficits will rise from $800 billion this year to $1.5 trillion in 2028. This is not good for the nation’s long-term economic health.

After strong 3.1 percent economic growth in 2018 (adjusted for inflation), CBO projects that growth will settle into a slower pattern of roughly 1.7 percent annual increases from 2023 to 2028.

No concerted efforts are being made to rein in the debt, expand the workforce, or invest in a more productive one.

The short-term spurt is due to fiscal stimulus from recently enacted tax cuts and spending increases. The eventual slowdown will be due to slower workforce growth, lagging productivity, and rising debt, which diverts capital from investment.

Looking behind the numbers reveals that we are doing little, if anything, to combat the forces that produce such anemic growth projections. Specifically, no concerted efforts are being made to rein in the debt, expand the workforce, or invest in a more productive one.

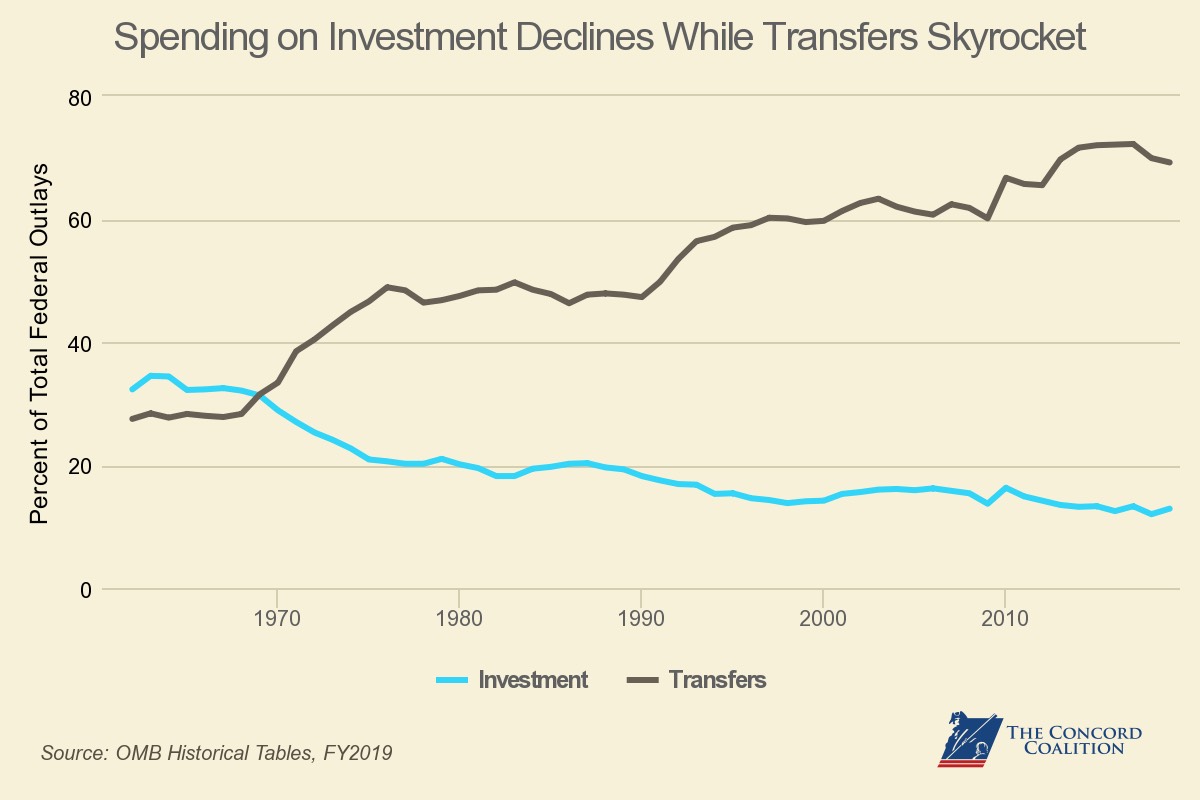

The trend is illustrated by comparing what Washington spends on transfer payments and what it spends on investments.

Roughly three quarters of the federal budget consists of transfer payments — government programs designed to provide income (or pay bills) in cash or in kind to individuals and families. The largest transfer programs are Social Security, Medicare and Medicaid, which together totaled $1.9 trillion in 2017.

Much less of the budget goes toward investments including physical improvements, research and development, education and training. This totaled $529 billion in 2017.

It wasn’t always that way. Fifty years ago, the federal government spent more on investments than on transfer payments. In 1967 investments amounted to 32 percent of the budget and transfers were at 28 percent.

By 2017, investment spending had plunged to 13 percent of the budget and transfer payments had ballooned to 72 percent. This dynamic means we are investing less in the productivity of the workforce even as we expect that workforce to bear the cost of rising transfer payments, which we are doing nothing to slow.

The trend is likely to worsen in the coming years because of demographics and the mechanics of the budget.

As noted, the largest transfer payments go for programs related to retirement and health care. These programs will grow in cost as the population ages and per capita health care costs continue to rise. Moreover, spending for these programs is considered “mandatory,” meaning that they grow automatically based on eligibility and payment formulas.

Investment spending, on the other hand, is concentrated in the “discretionary” portion of the budget, which is more sensitive to constraint because it must be approved each year through the congressional appropriations process.

This portion of the budget has borne the brunt of recent efforts to restrain spending. The CBO projects that, under current law, discretionary spending will decline over the next decade to a much smaller percentage of the economy than it has averaged in the past.

Transfer programs are crucial for many families, but a budget composed overwhelmingly of transfers and little of investments does not provide the tools for sustainable, long-term economic growth.

Investment in physical and human capital is a key mechanism through which lawmakers can strengthen the economy and promote sustainable growth.

Such growth depends upon two primary factors: workforce expansion and higher productivity per worker. Workforce growth is projected to slow substantially in the years ahead as the huge baby boom generation continues to enter its retirement years. So, economic growth will be increasingly reliant on greater labor productivity to make up for at least a portion of the slowdown in the number of new workers. Current federal spending priorities, however, do not reflect this need.

Investment in physical and human capital is a key mechanism through which lawmakers can strengthen the economy and promote sustainable growth. Federal investments in education, infrastructure, basic science, and research and development, among other initiatives, played a central role in fostering the strong economic growth that the United States has experienced since World War II.

According to CBO, roughly half of nondefense discretionary spending from the 1980s onward has consisted of federal investments that have contributed to productivity growth. Consequently, “lower nondefense discretionary spending as a percentage of GDP would mean less federal investment, causing [productivity] to grow more slowly.”

For the United States to continue experiencing the robust economic growth it has enjoyed since World War II, the federal government must support investment by focusing its outlays on programs that maximize physical and human capital development. In addition, lawmakers must put key transfer programs on more sustainable paths to ensure their existence for future generations.

By increasing the sustainability of transfer spending and supporting federal investment, lawmakers can better prepare the nation for sustained long-term economic growth.

Robert L Bixby is Executive Director of The Concord Coalition.