As I look through the difficult and critical circumstances in which we find ourselves, I’m quite convinced that when times are hard the most important thing you can do is to go back to first principles, go back to your values, go back to what guides you – the lodestar that should move you forward. So I’d like to entitle my remarks, “Why Democracy Matters.”

It’s a bit odd, I think, that a former Secretary of State would have to actually defend the proposition that democracy matters. But I think we better start defending that proposition. In part, I’m driven to talk about this because I served in a pretty controversial and consequential time over the last eight years But as many controversial matters that came before us, the one that seems to have been most controversial was to speak firmly for the democracy agenda – for the freedom agenda.

People said we were too idealistic to believe that democracy could spread to the corners where it had never taken root – that it was impractical, somehow. That somehow it was not serving U.S. interests to speak strongly and firmly for the rights of every man, woman and child to live in freedom. That somehow it was not practical to believe that people – regardless of their station in life, regardless of their culture, regardless of their circumstances – would want to enjoy the very rights that we all enjoy. That somehow that was impractical and was too idealistic.

But you know, standing for democracy as the United States of America is both practical and right, and that’s the proposition that I want to defend.

Freedom is our Best Ally

The United States has got to stand for the universality of freedom and the universality of democracy. It has to stand for it because it is right — it is the moral thing to do — but also because it is in our interest to do so. President Reagan, in his second inaugural, had one simple line that captured that. He said, “America must remain freedom’s staunchest defender, for freedom is our best ally.” Remain a staunch defender because it is right, but also because freedom is our best ally.

The United States has got to stand for the universality of freedom and the universality of democracy. It has to stand for it because it is right — it is the moral thing to do — but also because it is in our interest to do so.

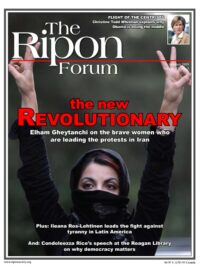

So why is this proposition so controversial? Well, there are several objections. One, that you cannot impose democracy. You cannot impose it by bayonet point, you can not impose it from abroad. This is most certainly true. But the fact of the matter is, if we look around the world and we look, for instance, at the recent events in Iran, we see something that I think is a fundamental truth: you don’t actually have to impose democracy, you have to impose tyranny. If men, women and children are asked, do they want to have a say in their future or would they have it dictated to them from on high?, they will choose to have a say in their future. And so, you don’t impose democracy, you impose tyranny.

What about the argument that there are people who are perhaps just not ready for democracy? Well, this to me is one of the most patronizing things that one can say. We are ready, but they’re not. And by the way, it’s been said at various times about a lot of people. It was said once that Latin Americans weren’t ready for democracy. They were given to military juntas and coups. They didn’t care about democracy. It was once said that Africans didn’t care about democracy. They were just too tribal and, of course, it didn’t matter to them that they had a right to have a say in their future. And, by the way, it was once said of black people. They were too child-like. They didn’t care about the vote. They weren’t really ready for democracy.

Well, of course, everyone is ready for freedom and ready for democracy. It may well be that economic circumstances are such that it makes democracy hard. It may well be that the absence of traditions in democracy make democracy hard. It may well be that the absence of civil society — of a strong fabric to society — makes democracy hard. But saying that democracy is hard and saying that someone is not ready for democracy are two very different things. The idea that there are some who are just not ready for democracy is both patronizing and it is insidious.

Third, there’s the argument that perhaps countries can go through authoritarian capitalism and do quite well anyway, so why bother with democracy? Of course, the example that is most often given here is China. They’re doing quite well, thank you very much, with authoritarian capitalism. But one has to wonder if this is a long-term proposition for success because, after all, it’s awfully hard to tell people that they can think at work but not at home. And one wonders if the tremendous economic success of China that is clearly quite extraordinary is not creating the kinds of strains and stresses in that society that ultimately will not be dealt with by a rigid political system governed from the top down.

I don’t mean to suggest that China is in danger of collapse. But there is one wonderful thing about democracy – it’s big and it’s messy and it’s chaotic. Someone once called it “controlled chaos.” Well, you might wonder sometimes about the controlled piece, but it is accordion-like. It is capable of giving people institutions in which they can try and resolve their differences peacefully. It is capable of giving people a say in how those differences are resolved. And finally, if you don’t like those who are governing you, you can throw the bums out. That, more than anything, is the final shock absorber.

You see in China instead growing strains and stresses from this tremendous economic and social upheaval. We’ve seen it in many ways. We’ve seen it recently with the riots among Uyghurs, the people of East Turkmenistan as the Chinese call it, who are unable to unable to express themselves because, if there is difference and it is in a dictatorial society, there is only one way to deal with it – somebody suppresses somebody. So ethnic rights tend not to be protected in authoritarian societies. We saw it when China had difficulty after the earthquake explaining to the parents of Chengdu, the place that I visited after the earthquake, why the school collapsed and killed children but the party headquarters, just a little ways away, didn’t collapse. The anger of those parents at the shoddy workmanship in that school was palpable. They had really nowhere to go.

We saw it in the product safety issue in China, where the government seemed to be unable to deal with it, where their solution was to execute the guy who dealt with product safety. Now this is not a long-term solution, because sooner or later no one is going to want to deal with product safety. And so the question for authoritarian capitalism is, in the long run, can it reach an equilibrium? Can it tell its people to get wealthier, to have greater property interests and still to allow politics to be held in the hands of a very few? I think not.

Guided by History, not Headlines

There is finally the argument, perhaps more difficult and mostly used in the Middle East, that when you have democracy – when you have elections before a society is fully matured and civil society in the like – sometimes the bad guys win. And what do you do when the bad guys win? We faced this quite a few times during the period of my tenure in office. We saw Hamas win in the 2006 elections in the Palestinian territories. We saw Hezbollah do well in the 2005 elections in Lebanon. We saw Islamist parties do well in the first elections in Iraq.

But you know, an interesting thing has happened. The second time around, the extremists have not done very well at all. And one wonders why that is. I would suggest to you that while elections are not the only step that one must take for democracy, they are a fully necessary step. What you see is that in authoritarian societies, particularly in the Middle East, there was politics going on, but it was going on in the radical mosque and it was going on in the radical madrasas, and decent political forces were not allowed to organize.

In that freedom gap, as a group of Arab intellectuals called it, you got not only the organization of the most extreme forces, but you also got the kind of nihilist forces like Al Qaeda, a different kind of politics. Decent political forces did not come into be in the Middle East. But now in freer environments like Lebanon and Iraq and even the Palestinian territories, you are seeing that decent political forces the second time around are doing better. So in Lebanon, my favorite example, Hezbollah lost in this last election.

Now why did Hezbollah lose? Well, in part because it turned out they weren’t the great resistance movement. They used their arms against the Lebanese people in May of 2007, and you know what? The Lebanese people had a way to punish them. They punished them at the ballot box. Where else could the Lebanese people have punished a terrorist group like Hezbollah?

You see in Iraq that in the most recent provincial elections, the Islamist parties, the most extremist parties, the parties funded by Iran lost and more decent political parties did better. I think that it is quite possible that what we will see is that as elections take place in the first round, the bad guys may indeed win because they’re the best organized — they were in the radical mosque, they were in the radical madrasas. But as time goes on, the slogan, “Vote for us, and we will make your children suicide bombers” won’t do very well at the ballot box. If decent political forces with a different message can come forward, then this will turn out for the better.

So I don’t think that there are really good arguments for those who say that either the United States should not advocate for democracy, should not make it a pillar of foreign policy, or that we should just wait until somehow it naturally emerges — as if democracy somehow naturally emerges. People fight for democracy, and America has to be their ally in that fight. To be sure, elections are not sufficient. We have to support democratically-elected governments, because one important thing happens when people go to the ballot box – they expect more of their governments.

It’s also true that it’s not a straight line. There will be ups and downs, it will go back and forth, and part of the issue is not to lose heart when it does. Because we have to remember that history has a long tail, not a short one. I used to make not very many friends in the press when I would say to them that today’s headlines and history’s judgment are rarely the same. But it is true. If you look to any point in time, you can see that there were times when something looked so impossible, and not very long after it just seemed inevitable.

Would you have dreamed that, in 1991, the hammer and sickle would come down from the Kremlin for the last time? And in 2006, the President of the United States would attend a NATO Summit in Latvia. Those things that once seemed impossible in retrospect seem inevitable. And so history has a long tail, and our part is to do what is right for history, not what is right for the day’s headlines.

That was the essence of Ronald Reagan. I can remember when Ronald Reagan gave his landmark speech and called the Soviet Union the “evil empire,” and said that it would end up on the “ash heap of history.” I have to admit, I thought, “Oh my goodness — how undiplomatic.” But you know, it was right and it was calling it as he saw it. In calling it how he saw it, he emboldened a whole generation of people who knew that they were living in a society and a state that was a lie.

And he spurred leaders like Mikhail Gorbachev to try not to destroy the system, but to reform it. But of course it was rotten to the core. And in trying to reform it, Gorbachev did destroy it. And this mighty Soviet Union – with 30,000 nuclear weapons, 5,000,000 men under arms stretching 12 time zones – collapsed without a shot.

History has a long tail, but that long tail only comes out in our favor if we’re true throughout the whole entire period to our values and to our principles. We have to stand for democracy, and we cannot be neutral about what form of government is right.

Condoleezza Rice served from 2005 to 2009 as the nation’s 66th Secretary of State. This essay is drawn from a speech she delivered at the Ronald Reagan Library on July 14, 2009. The speech can be viewed http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qvOjtvXrlgI.