America’s first responders have trouble communicating among themselves

On September 11, 2001, the American people learned again how vulnerable our Nation was to a terrorist attack.

In the five years since, Congress and the President have taken a number of important steps to make sure we are not attacked again. Among other things, they have strengthened security at airports, established the Department of Homeland Security, and increased anti-terrorism spending to the highest level ever.

But in at least one important area, several Administrations and Congresses have been too slow in their efforts to keep our homeland secure. This area has less to do with our ability to prevent another attack than it does with our ability to respond to another attack or major natural disaster. More specifically, it has to do with the ability of our first responders to communicate with each other.

The attacks of 9/11 re-exposed serious problems in that regard. Stories abound of firefighters on the ground outside the World Trade Center not being able to talk to firefighters climbing the stairs inside because their radios were incompatible. Similar stories were heard from first responders at the Pentagon, as well. Lives were lost that day because of this kind of lack of communication. Unfortunately, this was not a new lesson learned. The responder community had cited communications interoperability as its number one concern for years before 9/11.

Post 9/11 progress remains slow. In fact, a June 2004 survey of 192 cities by the National Conference of Mayors found that 60 percent of those responding indicated that city public safety departments did not have interoperability with the state emergency operations center, while 88 percent did not have interoperability with the Department of Homeland Security.

Even prior to 9/11, the National Memorial Institute for the Prevention of Terrorism (MIPT) began sponsoring two programs designed to not only provide more information on the equipment and interoperability challenges our Nation’s first responders currently face, but propose a set of common sense solutions, as well.

The first program was called Project Responder. In recognition of the previously unthinkable threat of terrorists’ use of chemical, biological, radiological, nuclear and explosive weapons, Project Responder evaluated needed capabilities as stated by first responders themselves. It also studied the state of current technology and provided information that could help inform or provide a road map for federal and private sector research and development agendas.

Project Responder resulted in a comprehensive report titled “National Technology Plan for Emergency Response to Catastrophic Terrorism” (available on MIPT’s web site, www.mipt.org). One section of the report is devoted to “Unified Incident Command, Decision Support and Interoperable Communications” and has to do with a significant part of the capabilities needed by responders. In addition to the clear increases in capabilities that interoperable communications would provide, many other highly desired and needed functional capabilities could be enabled by interoperable communications.

These functional capabilities are currently not available, but could be achievable at low technological risk. They include: 1) point location and identification to help incident commanders know where their personnel and equipment are at any given time; 2) seamless connectivity to aid when multiple agencies and jurisdictions work together at a site; and, 3) information assurance to ensure the availability of information, as well as what is communicated, not be compromised by adversaries during a crisis.

Providing command information and dissemination tools and multimedia functional capabilities were also identified by Project Responder, but were not as highly prioritized as the previous three. One of the key findings was that technology already exists to achieve interoperable communications. New research and development into communications technologies is not needed to solve interoperability. Instead, Project Responder concluded that “organizational changes, equipment/interface standards, and practice/training may be more relevant than technology in solving some of the problems.”

The second MIPT initiative impacting interoperability issues is the Lessons Learned Information Sharing (LLIS) system. LLIS, which can be found online at www.llis.gov, was developed by MIPT in conjunction with the Department of Homeland Security. It is a national, online network of Lessons Learned and Best Practices designed to help emergency response providers and homeland security officials prevent, prepare for, respond to, and recover from acts of terrorism. LLIS reveals that interoperability is a recurring problem among first responders nationwide. In my mind, these projects highlight five challenges that need to be taken into consideration if these problems are going to be overcome.

The first challenge has to do with leadership. In short, Congress and the President must provide the first response community with a national vision for interoperable communications and strategies to make this vision a reality. State and local jurisdictions buy equipment based on their own needs and resources. Without an overarching national strategy, there will be no coherence to these purchases, and true interoperability will be all the more difficult to achieve.

The second area concerns the issue of frequency spectrum. Although Congress recently passed and the President signed into law legislation that will allow access to portions of the 700 MHz spectrum that first responders utilize and depend on, there will still be competition (with huge financial implications) over how much and what parts to dedicate to the emergency response community — and access to that part of the spectrum is still two and a half years away. I don’t know how much is enough, but all the major response associations have experts in that issue and we should pay very close attention to what they say is required and then have the national will to provide it.

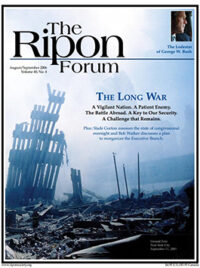

A firefighter walks away from Ground Zero after the collapse of the Twin Towers.

Stories of firefighters on the ground outside the World Trade Center not being able to talk to firefighters climbing the stairs inside because their radios were incompatible. Similar stories were heard from first responders at the Pentagon, as well.

Third, there is a lack of standards for interoperable communications. Progress is being made on that front, but it is painfully slow as all standards development efforts tend to be. Standards must include not only the technical elements, but must also insure that we have the necessary test procedures and protocols in place to allow for third party testing and certification. We insist on certification testing for responder personal protective equipment — we should do no less for their communications equipment.

Fourth, we need to think about how to establish a common operating procedure. I spent 30 years in the U.S. Army, and we always had a set of Signal Operating Instructions (SOIs we called them) which enabled all who came into an area of operations to know who to call and on what frequency based on their level of command and function. While it may be desirable to have the capability for everyone to be able to talk to everyone else, that would be chaotic and is not how we would want to operate.

Fifth, and after we have all of the above, we will have to deal with the issue of phasing out all of the legacy communications systems. With the millions of communications systems in existence today, we will have to be smart about that or we may waste enormous amounts of resources. Several bridging/gateway technologies already exist that can help us phase into standards compliant communications systems.

Of all these challenges, perhaps the most important one is the first one listed above. For in the end, it’s not so much about technology, though technology is obviously important. It’s about Congress and the Executive Branch forcing changes that should have been made years ago – changes that will help save lives and keep our Nation’s first responders more secure.

James M. Gass is Deputy Director of the National Memorial Institute for the Prevention of Terrorism in Oklahoma City.