Even for public servants with the best of intentions, the seeming intractability of poverty in America can be awfully discouraging. Its causes are complex and past efforts have met with limited success. Until Hurricane Katrina hit land, poverty had been absent from the public agenda for so long that there was little consensus among policymakers in how to respond. Not only was the toolbox of effective antipoverty proposals empty but partisan gamesmanship often seems to block innovative, good faith efforts to address it.

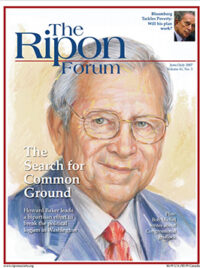

Yet persistent, concentrated, and intergenerational poverty remains a scourge upon our prosperous society, an enduring challenge for policymakers of all persuasions. One of the more remarkable efforts to meet this challenge is being led by New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg, who has decided to make tackling poverty one of the core priorities of his second term. With Democrat Charlie Rangel looking on, Mayor Bloomberg announced this past December one of the most innovative anti-poverty efforts to emerge in recent years. While it is too early to predict the ultimate fate of this effort, it has already unleashed an unprecedented public private partnership that just might create a model for future anti-poverty initiatives across the country.

While it is too early to predict the ultimate fate of this effort, it has already unleashed an unprecedented public-private partnership that just might create a model for future anti-poverty initiatives across the country.

Rather than identifying amorphous targets or unattainable goals, Mayor Bloomberg committed himself to remaking the toolbox. And he pledged $150 million a year to do so, some of it to be raised in the private sector. Much of the money will be used to try and test out new approaches. At the center of the effort is a newly-formed city office, called the Center for Economic Opportunity (CEO), which is designed to operate as a combination of a philanthropic foundation and a venture capital fund. This office will be charged with seeding innovation by supporting a range of experimental programs. But in addition to investing in R&D, the CEO will be in charge of evaluating the results, so programs that demonstrate success in reducing poverty can be built upon and those that don’t can be shut down. This results and evidence-based approach is gaining momentum in other areas of government, increasingly influencing budget decisions at the federal and state level, but the funding of policy innovation, especially in anti-poverty program at the local level, is breaking new ground.

Emblematic of the search for innovation is the decision to implement and test one of the more remarkable anti-poverty tools developed in recent years—conditional cash transfers. Piloted in demonstrations throughout the world but largely untried in the U.S., conditional cash transfer programs (CCTs) provide money directly to recipients when they meet specific criteria. It’s an incentive program that makes the social contract explicit. Families are rewarded for their actions, so they may qualify for a transfer when they complete a training program or make sure their children go to school and get vaccinated. The idea behind CCTs is to replace the traditional welfare model of donations of aid with one that allows recipients to invest in their future. It has already been proven to work in other places. One widely studied program in Mexico, one replicated internationally in over 20 countries, has been credited with improved health outcomes that have been linked to improved educational outcomes in young children and a reduction in poverty at the family level.

To implement and evaluate this approach in New York City, Mayor Bloomberg formed a public-private partnership in March of this year. The first of its kind in the U.S., Opportunity NYC is a $50 million effort that has raised support from a number of foundations, including the Rockefeller Foundation, the Open Society Institute, AIG, and Starr Foundation. Designed with input by MDRC, a leading national evaluation and research firm, the Opportunity NYC program will include a sample of approximately 5,000 families throughout the city — half of which will be part of a control group. The incentive-based strategies of the program will focus not on developing new social services, but on increasing participation in certain existing programs and taking actions that have already been proven to reduce poverty among children and families now and in the long run. Participants may receive $50 to $300 for meeting specified targets or completing a conditional activity, and families may be eligible to augment their income $3,000 to $5,000 per year depending on the activities and family size. Initially, incentives will focus on the areas of education, health, and work, but poverty advocates are already identifying promising areas to expand the effort.

The incentive-based strategies of the program will focus not on developing new social services, but on increasing participation in certain exciting programs and taking actions that have already been proven to reduce poverty among children and families now and in the long run.

Another set of early investments will focus increasing the financial capacity of lower-income households. A first-of-its-kind Office of Financial Empowerment is being formed to ensure that families have access to information that can maximize their financial health and minimize the likelihood that they will be subject to predatory schemes. This will include coordinated information campaigns to publicize the availability of tax credits and public benefits which can families get and save financial resources. The idea is to provide and coordinate access to asset building activities, such as basic bank accounts, financial literacy help, and matched savings account programs.

An additional plank of the effort is designed to help families with young child enter and stay in the work force. Recognizing that child care costs often impede labor force attachment, the Mayor has taken up an earlier proposal of his Democrat-led City Council to create a local child care tax credit that could help offset these costs and make work pay. The proposed credit, still pending before the council and state legislature, would target families with children three years old and young which have household incomes less than $30,000. It is estimated that this proposal would cost the city $42 million a year and benefit almost 50,000 families.

This initial round of investments is ambitious in both its scale and breadth—a testament to a driven, second-term mayor committed to forging new ground in some difficult terrain. And yet, Mayor Bloomberg is not alone in his decision to focus on combating poverty or in his search for new, effective ways to confront it. Across the country, mayors are increasingly turning their attention to these issues. Los Angeles Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa recently convened a task force of mayors to develop a forward-thinking anti-poverty action plan. The mayors acknowledged that reductions in poverty are unlikely to come from expanding subsidies and entitlement programs, but from revising the way we use public resources to create a lifelong ladder of learning and opportunity. Specifically, Villaraigosa has called for a revitalizing system of work skills and training, an expanded EITC to make work pay, and the provision of children’s savings accounts to provide a platform to build assets over a lifetime and learn the basics of financial education.

Like Bloomberg, these mayors recognize that there are no quick fixes. This current crop of politicians may be long gone before we realize what works, making these efforts all the more laudable. But they have launched a necessary first step, which is an active search for policy interventions that can work over the long term.

Reid Cramer is Co-Director of the Next Social Contract Initiative and Research Director of the Asset Building Program at the New America Foundation in Washington, D.C.