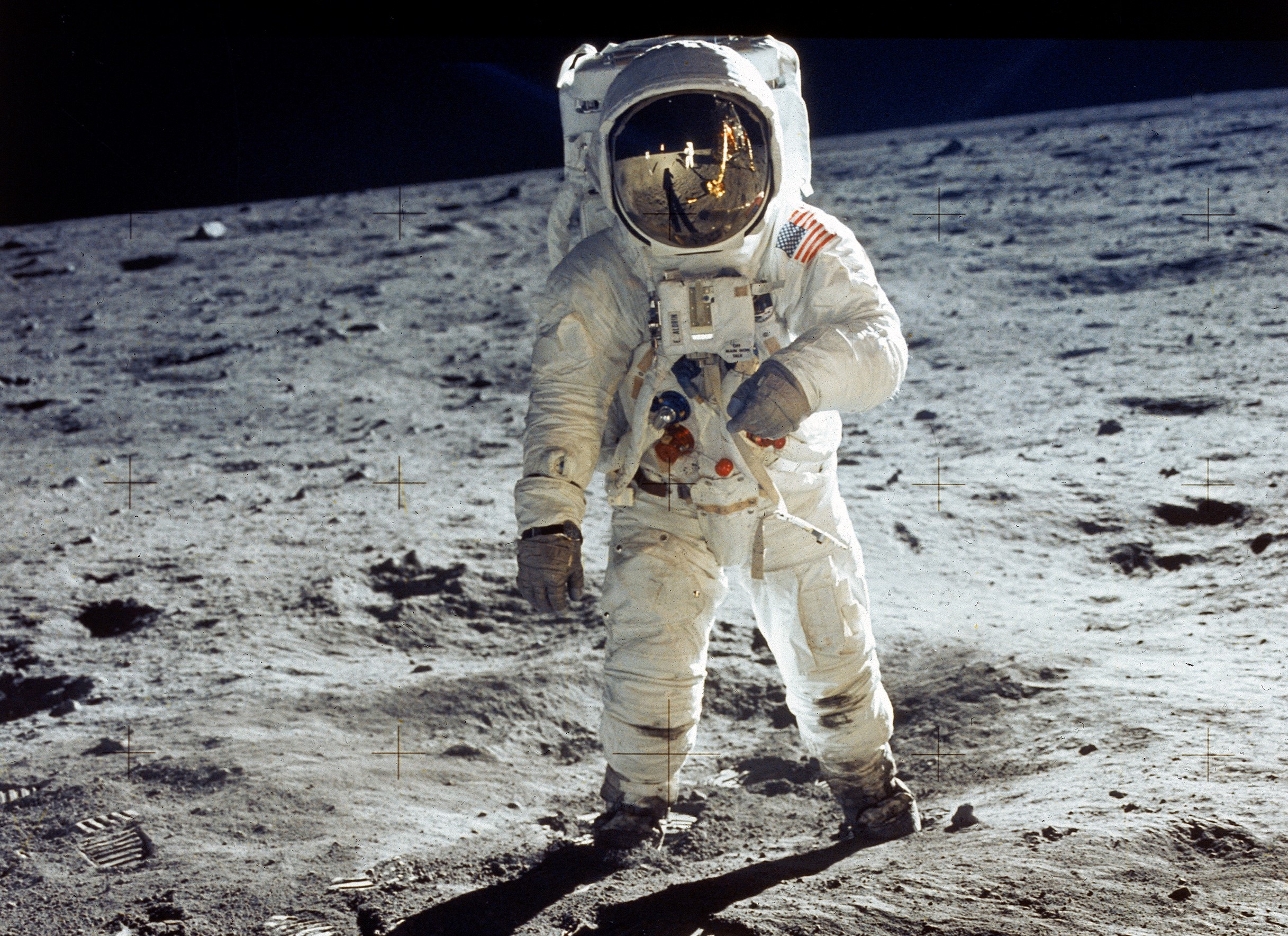

If you were alive and of a certain age in 1969, you most likely remember where you were on July 20th of that year. In all likelihood, you also remember the rest of that decade. It was an era of unrest in America – of marches and protests and violence and war. The Apollo 11 moon landing on that singular summer night stands out as one of the few bright spots in an otherwise dark period.

Of course, it wasn’t just a bright spot at that particular moment of American life. It was one of the brightest spots ever in the history of humanity. It was the moment that humans broke the bonds of Earth orbit and set foot on a celestial object that was not their own. “One small step for man, one giant leap for mankind.” Neil Armstrong’s words as he stepped off of the lunar lander could not have been more fitting. They are etched in the ages, and mankind will remember them forever.

With America and the world marking the 50th anniversary of this giant leap next month, we thought it was a good time to look back on the period in which it took place. We do so with Douglas Brinkley, the Katherine Tsanoff Brown Chair in Humanities and Professor of History at Rice University. Brinkley is a CNN Presidential Historian and a contributing editor at Vanity Fair. He is also the author of, “American Moonshot: John F. Kennedy and the Great Space Race.”

The Forum spoke with Brinkley recently about his book, the early years of the space program, and whether – in this age of national debt and political dysfunction – it is even possible for such a momentous undertaking to happen in America again.

____________________________________

RF: Talk for a moment about the birth of the space program in the late 1950s. What was the mood of the country – and the world – at that time?

DB: In the 1950s, the question was, “Would the United States or the Soviet Union become the first nation to send human beings into space?” The big, shocking moment was when the Soviet Union launched the Sputnik satellite into orbit in October of 1957. Many Americans thought we were losing the Cold War if we were behind in satellites. In response to Sputnik, President Dwight Eisenhower moved forward with Congress to create NASA.

What’s interesting about the birth of NASA the following year is that it was about civilians in space. Ike wanted to make sure we weren’t militarizing it. And so an effort was made to begin pulling our best scientists, academicians, and engineers, into thinking about how we could explore space and possibly go to the Moon.

RF: Eisenhower started the space program, but one could argue that Kennedy kick-started it by calling for America to land a man on the Moon by the end of the decade. Why did he make this bold declaration?<

DB: For one thing, Sputnik happened on a Republican President’s watch – Eisenhower’s. Kennedy had been elected to the U.S. Senate in 1952 and was running again in 1958, and part of his stump speech was that the U.S. was falling behind the Soviet Union in STEM research, not just in space, and that we needed to do more in our high schools to teach math and science.

He said it was a national security imperative that we were able to at least have parity with the Soviet Union on satellites, because satellites are about rocketry in the end. And if we were falling behind in ICBMs and intermediate range missiles, then the United States itself was vulnerable. Kennedy is the one who coined the phrase “a missile gap” with Russia. He got traction with that message when he ran for the Senate, and he continued it when he ran for the presidency in 1960.

There is a crucial moment in the debates between Kennedy and Richard Nixon, Ike’s Vice President, when Kennedy says, “You told Mr. Khrushchev that America is number one in kitchen appliances and colored TVs. Well, I’ll take my TV in black and white. I want to be number one in rocket thrust.” At another moment in the debates, Kennedy tells Nixon that, “If you’re elected President, I see a Soviet flag planted on the Moon. I want to see an American flag on the Moon.” And so he wrapped himself up into a kind of “Rah-Rah” space exploration mode. In fact, the term “New Frontier” that Kennedy used was a phrase frequently used in NASA culture.

Then when he became President, the Soviets, in April of 1961, launched Yuri Gagarin into space. They had won the sweepstakes – they had launched the first human being into outer space. And that happened on JFK’s watch. And so he became fiercely determined to match the Soviets with an astronaut. He green-lit Alan Shepard going into space on May 5th, and then later that same month – on May 25th – he went before a joint session of Congress and made his famous pledge to land a man on the Moon by the end of the decade and bring him back alive. At that time at NASA, people were like, “You’ve gotta be kidding me – we don’t have the technology to go to the Moon.”

“Kennedy was a master salesperson. He sold the Moonshot to space with great fortitude and verve.”

But in the end, that was the whole point of it – the Apollo program – to start marshaling the universities, the scientists, the Fortune 500 companies, the Armed Forces, and the government agencies together in a collective endeavor that would improve American science and space exploration – all in the name of peace, not war. So instead of fighting a proxy war like in Korea versus the Soviet Union, Kennedy thought why don’t we just have a race to the Moon? And he kind of frames it as a battle between democratic capitalism and communist totalitarianism. And he was a master salesperson. Kennedy sold the Moonshot to space with great fortitude and verve.

RF: The 1960s were a divisive time, to say the least. How was JFK, and then Johnson after him, able to unify the country behind this singular goal?

DB: Because we’d had success during Kennedy’s presidency. We had six Mercury missions, and all were successful. It created heroes out of Alan Shepard and Gus Grissom and John Glenn and Scott Carpenter and Gordon Cooper. They became the biggest celebrities in the country – the space stars. And so there was a public appetite for space.

Now, there were many that thought going to the Moon shouldn’t be the top priority – people on the right like Senator Barry Goldwater of Arizona, and people on the left like William Fulbright of Arkansas. And Eisenhower, as well — he called it a “stunt.” So it had its critics, but there was enough of a feeling in the country to take on the challenge, and it never got defunded. And by the mid-1960s, over 4% of our annual budget went to NASA.

In the end there were 400,000 Americans who took part in one way or another in the effort to get us to the Moon. It was a cause for celebration, because from the beginning of time, everybody has looked to the Moon. It controls our tides and rivers, we mark our calendars around the moon, and it’s been romanticized by poets and painters. And we never really were able to touch it before. Then suddenly, there’s Neil Armstrong of Ohio walking on the Moon and leaving bootprints on it. It was the high water mark of American can-do-ism.

RF: Flash forward to present day. The country is divided, though perhaps not as divided as it was in the ‘60s. And in terms of our budget, the national debt is clearly going through the roof. Do you think it is possible to unify the country behind another goal of this magnitude in this age of debt and dysfunction? Put another way, can we still do great things?

DB: Americans still do great things, but in this current political climate, particularly with the 2020 presidential election looming, it’s going to be hard to galvanize public support behind one grand endeavor. For example, the problem of climate change is so intense that many people talk about an “Earthshot” to repair our damaged planet. And then there are others, like Buzz Aldrin and Michael Collins, two of the Apollo 11 astronauts, who want a “Mars-shot.” So people are looking for an idea that might pull the country together.

But Donald Trump is a politician who plays divide-and-conquer. He’s not a unifier. And you have to have the right kind of spirit to pull our society together on a big endeavor like that. A mission to Mars may happen – because we want to beat China there. Or we’ll go back to the Moon because we want to explore the ice cap on the South Pole. Or it may be that after 12 white men on the Moon, the public decides it’s time for a woman to walk on the Moon. I believe it will happen at some point, but timing is crucial. In history, there’s a moment – there’s a season – for everything. I do think there is a national hungering for another Apollo 11-like endeavor. But it will take presidential leadership to pick what that is. Barack Obama focused on the Affordable Health Care Act and ate up a lot of oxygen. Donald Trump wants a wall between the Mexico and the U.S. Both of these are very divisive.

“I do think there is a national hungering for another Apollo 11-like endeavor. But it will take presidential leadership to pick what that is.”

The Moonshot didn’t have that kind of divisiveness, because once Alan Shepard went into space, everybody was begging for more. And you know, America is fueled by optimism. You can’t run on negativity or pessimism or insults or anger. It’s about we can do it. That’s why I keep using can-do-ism. American exceptionalism means that we’re an amazing country and a great democracy, and if we pull our collective self together, we can do great things.

RF: Finally, let’s return to the main protagonist of your book – JFK. How would he handle some of these challenges and confront the problems facing our nation today?

DB: Kennedy would try to unify the country. That was the whole point of his inauguration and his presidency. What that means is that if we’re going to Mars, be a President who gets out there and says we’re going to Mars. Visit the space ports. Interact with the companies that will be involved. Stoke the public’s imagination. We forget that some of our great Presidents were just masterful at moving public opinion.

I wrote on Theodore Roosevelt and the national parks and conservation. He saved 234 million acres of wilderness in America, not because the public was clamoring for it, but because he believed we should save our beautiful places and he led. That’s what Kennedy brought to the space technology realm. Ever since 9/11, we’ve been little more than a kingdom of fear.

Instead of being optimistic about the future, you’re hearing a lot of stories about American decline, about our broken politics, and about a general malaise across the land. If Kennedy were here, I think he would say, “Nonsense. America’s best days are yet to come!”