The 24/7 news cycle and its impact on politics today

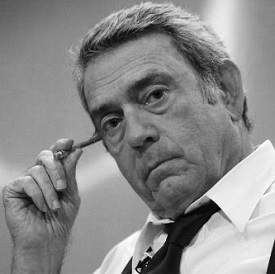

by DAN RATHER

The ongoing presidential election campaign will be, by its end, the longest in American history. It will also be the campaign to receive the most media coverage – an inevitability owing to the omnipresence of media and the accumulation of network and cable news hours, column inches, and web pages over the many days that will have passed between the candidates’ announcement speeches and Election Day.

We might ask what relation all this quantity has to quality: Does more equal better? Or does more, in this case, actually amount to less?

The advent of 24/7/365 news coverage, with the proliferation of cable news stations that followed CNN’s launch in 1980, has carried a great but largely unfulfilled promise to those who care about the state of our nation and our world. The promise is—or, at least, was—that, freed from scheduling and time constraints, these outlets (and the new media that have followed) would have a chance not only to cover breaking news in a way that the television networks cannot or will not, but would also be able to devote time to a more in-depth exploration of news stories that are either woefully condensed or passed over entirely by the networks’ half-hour, evening news programs or even their hour-long “magazine” programs.

It must be recognized that the idea of 24/7 news coverage counts for little without the will to make meaningful use of of all that time and, significantly the resources to make that will a reality.

Instead, we have seen 24/7 news outlets play a leading role in propagating many of the trends that most threaten our news and our politics. Among these are: the growth of soft news, infotainment, and celebrity coverage; the filling of time with video footage masquerading as news stories; and the in-studio shouting matches that, these days, pass for reasoned debate of political positions.

This is a short list of areas that should give particular concern (and one from which network news—in which your writer spent 44 years as a correspondent, anchor, and managing editor—cannot be and should not be exempted). Taken together, they lend themselves to a news environment in which the primary focus of political coverage is on process (e.g., fundraising, polls, campaign strategies and image-building) rather than policy, in which “stories” such as the “Dean scream” are given prominence far beyond their importance, and in which political discourse is reduced to opposing and unyielding talking points in a way that suits perfectly the goals of political strategists but which does harm to this country and its citizens (including their attitudes about politics and government.

It must be recognized that the idea of 24/7 news coverage counts for little without the will to make meaningful use of all that time and, significantly, the resources to make that will a reality. A day in its entirety amounts to a lot of time to fill. To gather, produce, and transmit news continually requires many highly-skilled and educated professionals and therefore a large payroll. To do it with a modicum of depth requires more of the same—having producers, correspondents, and crew persons in sufficient numbers to devote a certain percentage of one’s news resources to exploring stories that might not bear immediate fruit, such as investigative pieces, or detailed, nuanced examinations of policy. If these resources were available and brought to bear, we would come to understand that there really is no such thing as a “slow news day”—there is always something happening somewhere that bears closer examination, always a story that demands further scrutiny.

The evidence, from the news we see emanating from the eternal flicker of 24-hour news, suggests that the resources that are being provided are not adequate to realizing the promise of continuous coverage. Indeed, what the troubling trends outlined above have in common is they are cheaper and easier to produce than news of substance and depth.

Unfortunately, this is not only a matter of 24-hour news media failing to realize its potential; there is, of course, room for improvement in how everyone does the news. But a non-stop news cycle creates its own dynamic, one that amplifies the effects of cheap news and news done on the cheap. The quick and easy “stories”— the aforementioned whoop by Howard Dean during the 2004 campaign, the raft of syntactical miscues by President Bush through his campaigns and presidency, John Edwards’ $400 haircut, and on and on — not only serve as a sorry substitute for more substantial news; they also, through the repetition and elaboration of the 24-hour news media machine, lend our political debates and campaigns an atmosphere of superficiality and lowest-common-denominator characterizations more befitting a schoolyard than the democratic deliberations of the world’s sole economic and military superpower.

It is impossible to ignore the role (or roles) that the Internet, despite its own promise and the difficulty of treating it as a monolith, has come to play in this dynamic. On the news-gathering side, certain precincts of the web offer a backdoor through which rumor and innuendo can enter traditional news organs—unverified stories, at times conceived anonymously and therefore without hope of holding their authors to account, can be covered by journalists who otherwise would not touch them, if they do so in the context of reporting “what people are saying online.”

The evidence, from the news we see emanating from the eternal flicker of 24-hours news, suggests that the resources that are being provided are not adequate to realizing the promise of continuous coverage.

On the news reporting side, the Internet sites of traditional publications and broadcasts (which are updated continuously, unlike their print and television parents) and Internet-specific sites such as blogs serve to generate, accelerate the growth of, and magnify the apparent importance of stories of dubious value. And so a political one-liner meant to provoke becomes, overnight or over the course of a day, a fusillade of soundbites exchanged between candidates or partisan interests—while substance and facts are crowded out. A speaking gaffe comes to dwarf a policy and serious discussion of its implications. And a lie, with apologies to Mark Twain, gets halfway around the world while the truth is still getting its boots on.

In a republic such as ours the news that comes out of our most prominent news organizations is of fundamental importance. What’s more, news consumers, along with journalists, news executives, and the people and corporations who own news organizations must understand that the constant proliferation of trivial stories, all day and every day, also has an effect on what goes in to the news. It affects the way our candidates for elected office communicate with us, and the ways in which those who gain office frame debates on issues touching on every aspect of our lives. This is the feedback loop of superficial coverage begetting superficial politics begetting superficial coverage that has enriched so many political media consultants while leaving our democratic institutions the poorer.

It has been said that a nation gets the politicians—and the politics—it deserves. If we as a nation truly feel we deserve a higher level of political discourse than we have seen in recent years, we must direct our calls for change not only at our politicians but also at our news organizations and those who own them. For it is they who facilitate and in no small degree make necessary the devolution of our campaigns and our national conversations into divisive name calling, empty talking points, and endless spin.

Dan Rather is the anchor and managing editor of Dan Rather Reports on HDNet.