In 1995, when Fortune first published its Global 500 ranking, China had only three firms on the entire list. In 2021, it not only had three firms just in the top 10, but had more total firms than any other country, including 11 more than the United States.

In 1995, when Fortune first published its Global 500 ranking, China had only three firms on the entire list. In 2021, it not only had three firms just in the top 10, but had more total firms than any other country, including 11 more than the United States.

Back in 1995, when we would ask U.S. executives to name key Chinese competitors, most could not. Today most can, even if they can’t pronounce their names and simply refer to them by their initials such as SAIC (Shanghai Automotive Industrial Company), ICBC (Industrial and Commercial Bank of China), or CNOOC (China National Offshore Oil Company). Similarly, in 1995, many, if not most, American policymakers and politicians believed, or at least hoped, that greater commercial engagement by and with China would lead to greater liberalization within the country. Few, if any, believe that today.

Over the past two-and-a-half decades, China’s economy and commercial enterprises have grown in size and scale such that no one can overlook them. However, our research and work with top executives globally suggest that many nonetheless retain two critical misperceptions. First, where many see scores of independent, multibillion-dollar enterprises, there actually lies a multi-trillion dollar monolith. Second, where most see individual competitive tactics and actions, there is an overarching, comprehensive competitive strategy and battle plan.

From our perspective, unless and until these misperceptions are corrected, both executives and policymakers risk miscalibrating China’s threats and opportunities and miscalculating their own responses.

Chinese Enterprises vs. Enterprise China

The size of the 135 individual Chinese companies on the Global 500 list, and thousands more beyond that list, deserve careful assessment and analysis. However, looking at them individually can easily obscure the collective monolith that includes not just these firms but also an entity not on the list. That entity is the number one employer (386 million) and the second largest revenue generator ($1.3 trillion) on the planet today. We’re talking about the Chinese State, which includes national, regional and municipal governments. It is this commercial totality that we should assess and analyze. We label it “Enterprise China.” Our first key point is that competing against Chinese enterprises is not the same as competing against Enterprise China.

Some executives and policymakers might be inclined to quickly dismiss the notion of Enterprise China as just the latest incarnation of industrial policy efforts, such as “Japan Inc.,” designed to benefit their indigenous firms—efforts that over time did not live up to alarmist’s predictions. However, the size and scope of Enterprise China both in absolute and relative terms are unlike any we have seen before. There are roughly 150,000 State-Owned Enterprises (SOEs) in China, and collectively they account for at least 30% of the economy, or $4.5 trillion in revenue. That share alone is greater than the total GDP of any other nation except the United States and Japan.

The level of ownership, control, and support of China’s SOEs is also without precedent. In terms of control, the top executives of these SOEs are appointed by and serve at the pleasure of their state owners. Most of the executives heading these entities come from the political ranks of the CCP (Chinese Communist Party). As an example of the unprecedented level of support the State provides to these SOEs, consider that even though SOEs only account for 30% of the Chinese economy, their debt levels exceed 90% of China’s total GDP. Privately-Owned Enterprises (POEs), which account for more than double that share of the economy, have debt levels that are less than one-third of that held by SOEs.

There are roughly 150,000 State-Owned Enterprises (SOEs) in China, and collectively they account for at least 30% of the economy, or $4.5 trillion in revenue. That share alone is greater than the total GDP of any other nation except the United States and Japan.

However, even this expanded view of Enterprise China is not complete. The scale and scope of Enterprise China is not limited to just SOEs. The State has nurtured and exerts significant control over most large, private firms as well. We refer to these as State-Influenced Firms (SIEs). Evidence abounds of the State’s ability and willingness to exert influence, if not control, over these firms. Consider just two recent cases — Ant Financial and Didi. Ant Financial was set for an IPO in 2020, which was expected to bring in $35 billion. It would have been the largest IPO in history and would have valued Ant at about $315 billion out of the gate. At that level, Ant would have been worth more than Société Générale, Deutsche Bank, Credit Suisse, Barclays, ING, Santander, and Goldman Sachs combined. As most readers likely recall, the Chinese government stopped the IPO, sanctioned parent Alibaba to the tune of $2.8 billion, and put Alibaba’s founder and leader, Jack Ma, on ice and out of public view for months. Similarly, not long after listing on the New York Stock Exchange, Didi, the largest ride sharing company in the world (with three times as many drivers and twice the revenue as Uber), was forced to delist from the New York Stock Exchange by the Chinese government. The message was not lost on any Chinese enterprises: The State calls the shots in the end.

Enterprise China’s Competitive Vision and Strategy

But even if one were to accept the scale and scope of Enterprise China as gigantic and unprecedented, the impact of this monolith could only be as large as the coordinated actions of all the component pieces. For that, there would need to be a grand competitive strategy and battle plan. There is, and it has been hiding in plain sight.

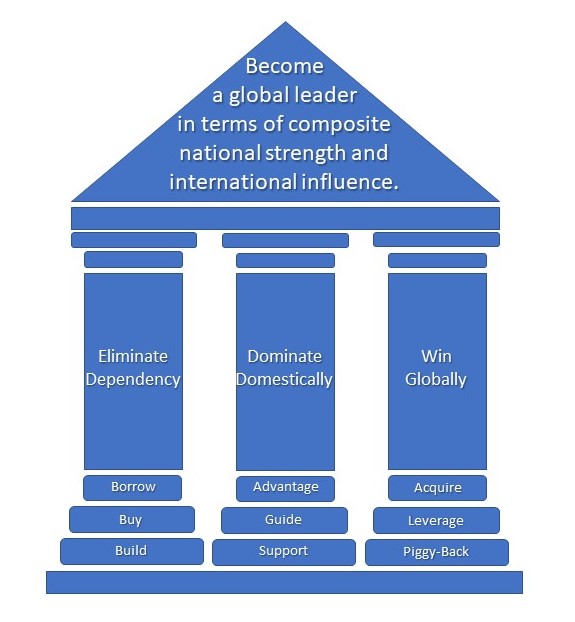

As professors of strategy, we observe and teach that strategy serves vision; therefore, to understand an entity’s strategy, you first need to understand its vision. Enterprise China’s “CEO,” President Xi Jinping, provided a succinct vision for the country to the 19th Party Congress in October 2017 when he stated that China would “become a global leader in terms of composite national strength and international influence.” As with any vision, this tells you where China intends to go.

The level of ownership, control, and support of China’s SOEs is also without precedent. In terms of control, the top executives of these SOEs are appointed by and serve at the pleasure of their state owners.

A strategy tells you how an entity plans to compete and win along the way. In China’s case, we do not have to speculate about its strategy; we do not need to break into government offices in Beijing and photograph secret documents. The key elements of the strategy are laid out in three public documents: National Medium- and Long-Term Science and Technology Development Plan (MLP spanning 2005-2015), Made in China 2025 (MIC 2025 spanning 2015 to 2025), and China Standards 2035 (Standards 2035 spanning 2020-2035). At its essence, this overall competitive strategy consists of three pillars: reduce dependency, dominate domestically, and win globally. The vision and strategy are captured in Figure 1

Strategic Pillar #1: Reduce Dependency

The first pillar of Enterprise China’s competitive strategy is to reduce its external dependency in key sectors. These sectors were laid out in the MLP and modified in MIC 2025. MLP primarily sought to reduce dependency in the targeted sectors by establishing local content goals of roughly 30% by 2020. The MIC upped those goals to 40% by 2020 and extended those goals out to 2025 with a target of 70% local content.

Enterprise China seeks to achieve these local content objectives and the resulting import substitution through three tactics: borrow, buy, and build, of which the greatest emphasis thus far has been placed on borrow and buy.

Strategic Pillar #2: Dominate Domestically

The second pillar of Enterprise China’s competitive strategy is to ensure that indigenous Chinese firms dominate domestically. This part of the strategy is articulated primarily in MIC 2025. The key metric of this pillar is market share. In the targeted sectors, the desired market share for domestic entities ranges between 70% and 85%. The rationale for this strategic pillar is simple. If Enterprise China simply focuses only on local content requirements, it risks shifting its external dependency from offshore to onshore. For example, suppose because of local content requirements, Qualcomm switches from selling telecom chips that it made outside of China to chips that it makes in China. China could still be unacceptably dependent on Qualcomm—a foreign company based in a foreign country. However, if in addition to high local content objectives, Enterprise China takes steps to ensure indigenous firms control 70% to 85% of the domestic telecom chip market, its external dependency risk would not just move from offshore to onshore, it would diminish overall.

The scale and scope of Enterprise China is not limited to just SOEs. The State has nurtured and exerts significant control over most large, private firms we well.

There is an additional reason for dominating domestically—profit sanctuaries. By dominating domestically in targeted sectors, Enterprise China can create profit sanctuaries that better enable it to fund both Strategic Pillar #1, as well as Strategic Pillar #3, which we will discuss next.

Strategic Pillar #3: Win Globally

If Enterprise China were to limit its competitive strategy to just these first two pillars, it might soon find itself isolated and alone. In a globally connected world, ensuring prosperity at home requires winning abroad. In pursuit of this strategic pillar, Enterprise China employs three core tactics: acquiring international companies, leveraging domestic standards globally, and piggy-backing on its own foreign policy initiatives such as the Belt & Road Initiative.

Of these, leveraging technological standards deserves special note. In today’s connected world, much of the global utility of innovations and their financial returns come from interoperability. Consequently, Enterprise China believes the words of Werner von Siemens, the 19th-century German founder of the Siemens conglomerate: “He who owns the standards, owns the market.” This is the core of Standards 2035 and why Enterprise China seeks to establish standards in areas such as 5G at home and leverage them abroad.

Implications

Given the unprecedented size and scope of Enterprise China and its overarching competitive strategy, what are the implications for both executives and policymakers? The implications are broad and deep, but here we highlight just three.

1) Take the Wide View: Don’t Mistake What is in Front for What Is – If indeed Enterprise China is not just a collection of Chinese enterprises, and if common actions are not just coincidental but the result of an overarching national vision and competitive strategy, then both executives and policymakers would be wise to view Enterprise China through a wide lens.

To executives, we are not encouraging them to ignore individual companies or abandon tried and true tools of competitor analysis. We are only saying that those tools are necessary but insufficient. For example, U.S. mobile payment companies or firms with those services cannot simply look at Alipay or WeChat Pay and get an accurate lay of the land. Even expanding their field of view to the parent companies, Alibaba and Tencent, is not sufficient. Executives need to widen their lens to look at the larger ecosystem and the country’s overarching national strategy. They need to see that Enterprise China seeks to reduce (if not eliminate) its external mobile payment technology, products, and services dependency, seeks to ensure indigenous firms dominate domestically, and aspires to win globally. Only by taking a wide lens view can executives properly calibrate their opportunities and challenges, as well as calculate their actions.

Enterprise China’s “CEO,” President Xi Jinping, provided a succinct vision for the country to the 19th Party Congress in October 2017 when he stated that China would “become a global leader in terms of composite national strength and international influence.”

The implication is similar for policymakers. The moves in 5G by Huawei cannot be viewed in isolation. Even if there were no backdoor security risks in utilizing Huawei’s 5G technology, policymakers could only accurately assess the risks and take wise action by looking at the larger ecosystem of telecom in China and then placing that in context of Enterprise China’s strategy of reducing its dependency on external 5G technology, ensuring its indigenous firms dominate domestically, and leverage domestic standards to win globally.

2) Take the Long View: Don’t Mistake Today for Tomorrow — Although we can point back 15 or more years to the origins of Enterprise China’s current competitive strategy, we are not implying that it was all worked out from the beginning. It has evolved over time. Nevertheless, core elements have remained intact across nearly two decades, and new elements have leveraged that foundation to address the future.

Consequently, to executives we would say take care to not let the opportunities of the moment obscure the risks of the future. And the risks are significant. Take the case of Bombardier. It entered into a joint venture (JV) in China with China Railway Rolling Stock Corporation (CRRC) in 2014. After a promising start, it later discovered that not only was it being pushed out of China, but it was facing direct competition abroad from its former partner. To Bombardier’s dismay, CRRC was using technology that looked quite familiar in an open tender for subway cars in Boston, where CRRC underbid Bombardier by nearly 40%.

The implication to policymakers is similar. For example, today it may seem as though China is decoupling, and to some extent it is to reduce its dependency on the United States and other countries. However, those moves today will not well predict the extent or the nature of Enterprise China’s moves tomorrow. In the context of all three of Enterprise China’s competitive strategy pillars, any wish or prediction that China will largely and permanently decouple and go back to its isolated ways of the 500 years prior to the 20th century is folly. To set global standards, win, and influence globally, Enterprise China must engage and lead, not withdraw.

3) Play Hardball: Don’t Discount Rhetoric for Resolve — Finally, our research and observations over the last two decades lead us to conclude that Enterprise China’s determination to pursue and its resolve to execute its competitive strategy are high and should not be underestimated. As fiery as his rhetoric was in the summer of 2021, President Xi’s warning that any nation that tries to “bully, oppress, or subjugate [China]… will find [itself] on a collision course with a steel wall forged by 1.4 billion people” is only half the picture. Enterprise China’s competitive strategy is not just about protecting itself from foreign invaders; it is more fully about “going out” and influencing the world. Only in shaping the world can it control its own destiny. Therefore, the implication to both executives and policymakers is simple: Enterprise China is “in it to win it,” so expect to play hardball.

Conclusion

The size and power of the Enterprise China train coming down the track is unquestioned. Where the country wants to go in the future is clear. In looking forward, some predict that China will come to rule the world, while others forecast the country’s coming collapse. We are pragmatists. The scale and scope of Enterprise China and the comprehensiveness of its competitive strategy should be well understood and assessed. At the same time, Enterprise China’s design does not guarantee its destiny. In 2021, in a Harvard Business Review article, we laid out the factors that could derail Enterprise China’s grand plans. In the end, executives and policymakers alike should take a wholistic view of Enterprise China and its competitive strategy and monitor the potential derailers carefully. That is the most practical way to ensure taking wise actions both today and tomorrow.

J. Stewart Black is a professor of global leadership and strategy at INSEAD. Allen J. Morrison is a professor of global management at Arizona State University’s Thunderbird School of Global Management. They are coauthors of Competing in and with China: Implications and Strategies for Western Business Executives (Thinkers50).