The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development is not normally an organization associated with policies of limited government. While members of the Paris-based international bureaucracy include governments from North America and the Pacific Rim, the OECD is dominated by European welfare states.

Perhaps reflecting the mindset of those European governments, the Paris-based international bureaucracy is often a cheerleader for statist policies, and is widely seen as an advocate of Keynesian spending schemes and higher tax burdens.

But there are some professional economists who work for the institution, and they occasionally generate good statistics and analysis. For instance, a new working paper by Jean-Marc Fournier and Åsa Johansson, two economists at the OECD, contains some remarkable findings about the negative impact of government spending on national prosperity.

The methodology in the paper, entitled, “The Effect of the Size and the Mix of Public Spending on Growth and Inequality,” is not ideal. For all intents and purposes, the economists compare economic performance of the OECD’s big-government nations with the growth numbers from the OECD’s not-quite-as-big-government nations.

The OECD’s economists have crunched numbers and determined that reducing the burden of government spending can boost GDP by an average of 10 percent.

“Governments in the OECD spend on average about 40 percent of GDP on the provision of public goods, services and transfers,” the economists write. “The sheer size of the public sector has prompted a large amount of research on the link between the size of government and economic growth. …This paper investigates empirically the effect of the size and the composition of public spending on long-term growth. …the simulation assumes that in countries where the size of government is above the average level of countries in the bottom half of the sample, the government size will gradually converge to this level (36 percent of GDP).”

But since there are no small-government jurisdictions that belong to the OECD, that automatically restricts the potential results. By definition, we can only see the potential economic benefits of reducing the burden of government spending to 36 percent of GDP. That’s useful information, of course, but it would be very illuminating if the study also calculated the additional prosperity that could be generated if governments consumed about 20 percent of economic output, as is the case in Hong Kong and Singapore.

But even with methodological limitations, the study generates some powerful numbers. There would be much more prosperity if the big-government nations in the OECD reduced the burden of spending to 36 percent of economic output.

“This reform is phased in over 10 years,” the paper states. “Such a reduction in the size of the government could increase long-term GDP by about 10 percent, with much larger effects in some countries with currently large or ineffective governments.”

These results are remarkable, if not stupendous. We have major policy fights in the United States about reforms that might boost economic output by a couple of percentage points. Yet the OECD’s economists have crunched numbers and determined that reducing the burden of government spending can boost GDP by an average of 10 percent.

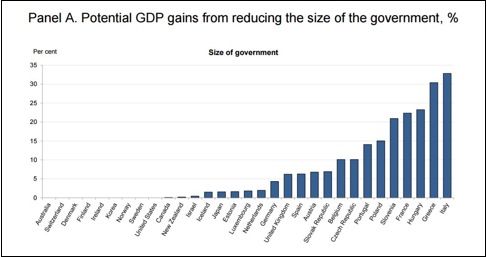

And for some nations, the potential for added output is far larger. The study suggests potential GDP gains of more than 30 percent for Greece and Italy. Smaller government could produce gains of more than 20 percent for Slovenia, France, and Hungary. And a leaner public sector could generate 10 percent more output for Belgium, the Czech Republic, Portugal, and Poland.

Below is the chart from the study that shows the potential growth effects for various OECD countries (keeping in mind that the paper’s methodology means that it is impossible for there to be growth effects for nations such as the United States).

It’s also worth noting that the study concludes that poor people would benefit from smaller government. This also is an important finding, since the OECD presumably included an inequality variable in hopes of weakening the argument for a lower burden of spending.

“…a reduction of the size of government has a positive, but moderate, effect on the income of the poor,” the authors of the paper write. “The average disposable income also rises. However, the rich gain relatively more. Finally, in countries where the government is less effective (such as Italy) the growth effect dominates and a moderate reduction of the size of government would have a large growth effect, so that it would lift all boats.”

The working paper also looks at the composition of government spending. In other words, just as not all taxes are equally damaging, the same is true for spending programs. Pensions and subsidies seem to cause the most economic harm.

“Reducing the share of pension spending in primary spending yields sizeable growth gains with no significant adverse effect on disposable income inequality,” the authors state. “Cutting public subsidies boosts growth, as public subsidies…can distort the allocation of resources and undermine competition.”

The moral of the story is that smaller government is good and free markets are good.

Another interesting finding in the working paper is that it notes that bad fiscal policy can be somewhat mitigated by having market-oriented policies in other areas, which is a point I always make when writing about Scandinavian nations.

“Countries with a high level of public spending may also be characterized by features that partly offset the adverse growth effect of government size … in Sweden the mix of growth-friendly structural policies…may have offset the adverse growth effect of a large government sector.”

In other words, the moral of the story is that smaller government is good and free markets are good. Mix the two together, and you have best of all worlds.

Daniel J. Mitchell is a senior fellow at the Cato Institute who specializes in fiscal policy, particularly tax reform, international tax competition, and the economic burden of government spending.