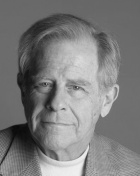

Author and Professor Theodore Lowi is widely credited with being the “father” of federal Sunset laws, having first suggested a “Tenure of Statutes” act in his 1969 book, “The End of Liberalism.” In recognition of his role in originating the idea, The Ripon Forum contacted Professor Lowi with a request that he write an essay discussing the genesis behind it. We expected a discourse on the need to make government smaller and smarter. What we received instead was a discussion that revealed his original intent had less to do with government efficiency than how our laws are made. Professor Lowi’s letter is below:

Thank you for the opportunity to set the record straight on my proposal for a “tenure of statutes” act.

It received a good bit of attention in the 1970s, due particularly to Common Cause, a prominent reformist group. They improved on it and, innocently, stole the idea from me by giving it a new and more quotable name: “Sunset legislation.”

What’s in a name? Damn near everything. I lost control of it, but took solace from Henry Adams, who observed, in his “Education of Henry Adams,” that you haven’t arrived as an author until you’ve been stolen from. I did occasionally receive some praise and more criticism, mainly from reformers of state legislation.

I improved on it in the second edition of “The End of Liberalism” in 1979, and in fact adopted the “Sunset” label with a footnote of explanation as an essential part of my appeal for “juridical democracy” as ammunition for my chosen enemy: “interest-group liberalism.” Thanks to Common Cause, Sunset got a lot more attention, but, alas, with almost nothing of me in it.

However, my frustration was not in the loss of my intellectual property. The frustration was that the idea lost substance as it became popular. The reformers concentrated on efficiency and short life – or, as the Ripon Forum put it, to make government smarter and smaller. My purpose was not at all to reduce the government, but to make each law real law – juridically sound law, laws with legal integrity.

Today we see it all over again, on a larger scale, with the last of the Bush administration and the beginning of the Obama administration. First, President Bush and the Democratic Congress granted the Secretary of the Treasury $800 billion for “bailouts,” as he saw fit. Then, President Obama and the Democratic Congress followed suit, with requests for still more money on top of the $800 billion and with no stipulation, no legislative guidelines – nothing but the designation of the Vice President as the overseer, coupled with the President’s assurance that, “No one messes around with Joe Biden!”

How’s that for a government of laws? These guys aren’t socialists. They’re interest-group liberals.

Unfortunately, interest-group liberalism thrives on bad legislative drafting. My antidote, then and now, has been revision by codification and clarification, guided by the wisdom of the 10 years of usage that revision is forced upon the agency as its statute confronts its demise. Interest-group liberalism, however, always wins because it has so many soldiers in the fight. The biggest enemies of good legislation are the law school professors, the rational choice philosophers, the relevant interest groups, the recent presidents, and the appellate courts. Law school professors and rational “choicers” thrive on “dispute resolution,” out of court and out of sight.

In fact, bad legislation has created a whole new subdivision of law schools, with a highfalutin name: statutory interpretation. Interest groups thrive on bad legislation because bargaining always favors well-heeled, well-organized, highly specialized interests. Presidents also prefer bad laws; they see broad delegation (without need of signing statements) as the source of “presidential power,” when in fact it is the source of mass expectations, making every president a failure. (I wrote a whole book about this in 1985 called, “The Personal President – Power Invested, Promise Unfulfilled.”)

And appellate courts accept bad legislation because they need a constitutional source if they intend to veto a statute when in fact (following Schechter and Panama) all a court needs is to say that the legislation is impossible to implement because Congress gave the Executive no guidelines.

In sum, I remain a frustrated reformer. But I’m not a pessimist. I’m a disappointed optimist.

Theodore Lowi is the John L. Senior Professor of American Institutions at Cornell University. He is the author or co-author of 18 books