My mental health was not high on my to-do list as I transitioned from the Coast Guard to civilian life. Extending my eight-year service contract by eight months to complete a medical board only deepened my depression. This extension kept me in Houston far from my family support system while adjusting to life with my new physical injuries. I was alone, I was hurt, and I worried about what my new future would look like. For many transitioning veterans, this remains the case.

More than 500 active duty service members transition to veteran status every day. Moving a family, finding housing, searching for employment, starting school, all while going through the complicated process of filing a Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) disability compensation claim, usually takes precedence over treatment for depression, anxiety, PTSD, or MST. This delicate time of leaving the routine, structure, and purpose the military provides while looking to new beginnings and unknowns can be a whirlwind of emotions for these new veterans as they work to successfully navigate their next life chapter.

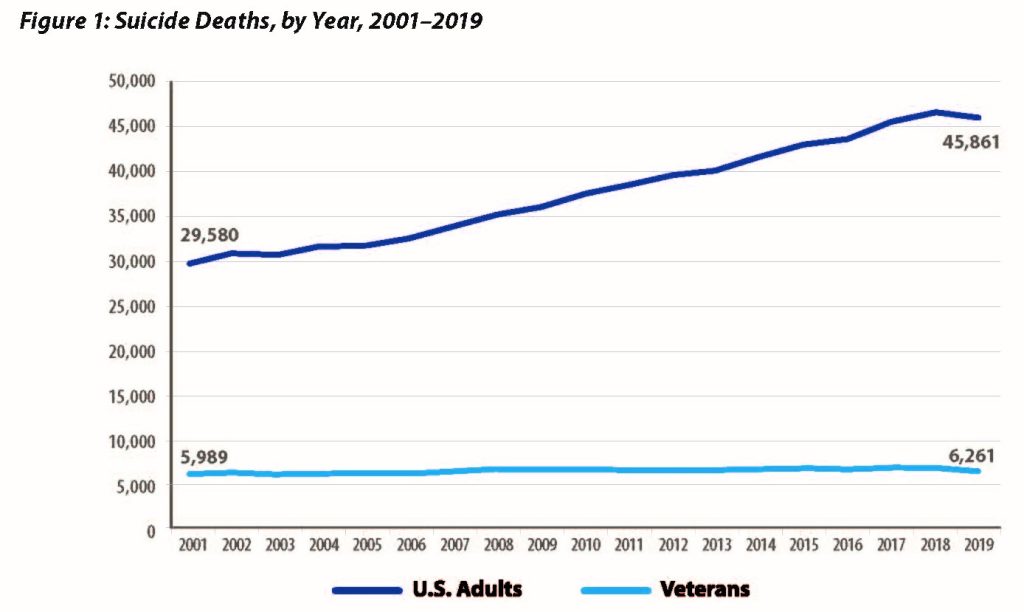

Recently, the VA created programs like Solid Start to address a gap in assisting veterans as they transition back to civilian life. This program reaches out to newly separated service members three times during their first year of separation to connect them with VA resources. Within the first year of this program, the VA contacted 60 percent of active duty members who separated in 2020. Sixty percent is a good start, but, according to the VA’s 2021 National Veteran Suicide Prevention Annual Report, veterans between the ages of 18-34 continue to have the highest unadjusted suicide rate. Therefore, more must be done.

Transitioning from active duty service member to veteran brings many challenges and mental health stressors.

Removing the barrier to access allows veterans the opportunity to receive mental health services from the VA shortly after their transition. Over the past 10 years, the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) increased upstream mental health programs to address suicide prevention. The VA expanded mental health services to meet veterans’ mental health needs even if they are not enrolled in VHA. The VA Mission Act of 2018 allows providers to deliver care via telemedical systems to veterans across state lines. Although access had increased, staff shortages still remain. Psychiatry is the most common severe clinical shortage in 60 percent of VA facilities, according to a 2020 Office of Inspector General report.

For 42 years, Vet Centers have been VA’s unheralded program. Vet Centers offer various services, including individual and family counseling, benefits explanation, substance abuse assessment and referral, and many others. There are over 300 centers, 83 mobile units, and several outstations and community access points to serve eligible veterans and their families, and yet, not many veterans know they exist nor do they know who may be eligible for service. Vet Centers operate without a proper staffing model to provide service for an increasingly eligible group of veterans and their families. Evaluating and understanding who uses Vet Centers and why will help to coordinate adequate staffing, resources, and funding.

Transitioning from active duty service member to veteran brings many challenges and mental health stressors. Therefore, these individuals are at a higher risk of suicide the first 12 months after separation and may require increased access to services. Expanding mental health access to both VHA and Vet Centers further reduces the barriers to care. While these programs are slowly moving the needle, they miss the mark on considering other aspects of a veteran’s life that may lead to crisis.

Therefore, these individuals are at a higher risk of suicide the first 12 months after separation and may require increased access to services.

As new legislation becomes law, new grants are given, and new programs are established, there remains a vast amount of unexplored VA data that can help better identify and understand the underlying causes of veteran suicide. Every year since 2014, the VA has published the National Veteran Suicide Prevention Annual Report. This report contains information from two years prior on veterans who died by suicide and their interaction with the VHA. The current annual report excludes other veterans’ benefits programs from the Veterans Benefits Administration (VBA). VBA programs such as the GI Bill, disability compensation, or home loan guarantee lead to workforce skill attainment, steady income, and stable housing, which are social determinants of health. Improvements to social determinants of health positively impact health outcomes, both mental and physical. Therefore, by including VBA data in the annual report, the VA will have a more complete picture of the impact of its programs on reducing the rate of suicide.

The VA’s top priority is the health and well-being of our nation’s veterans. If the VA is serious about understanding and preventing suicide, then we must demand a more thorough evaluation of all VA programs. Congress needs to direct the VA to include relevant VBA data in the annual report on all VA programs and their impact on veteran suicide. Much more needs to be done to reduce the number of veteran suicides to zero.

Tammy Barlet, MPH, is Deputy Director of the National Legislative Service for the Veterans of Foreign Wars of the United States. It is her responsibility to analyze and consult with Congress on issues related to women veterans and health care. She served eight years in the United States Coast Guard as an Operation Specialist Third Class Petty Officer between 1995-2003.