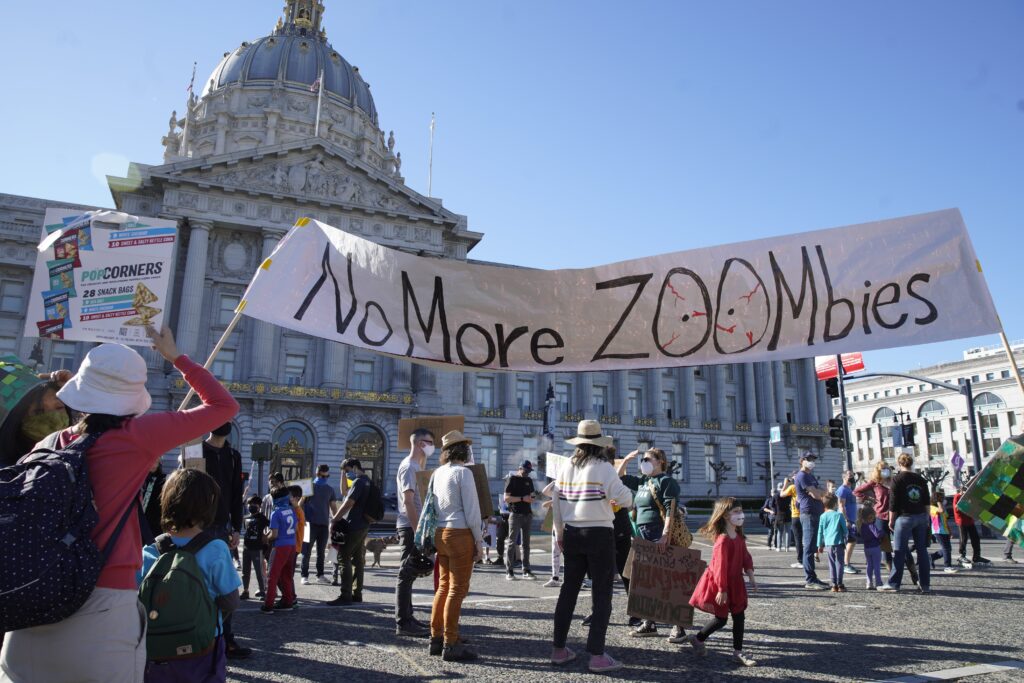

The pandemic has been devastating for America’s students. More than two years of prolonged school closures, masking, and disruption have been cataclysmic for their academic success, mental health, and social well-being.

Public school leaders estimate that half of their students began last year behind grade level in at least one academic subject. In three-quarters of schools, student quarantines or chronic absences disrupted learning last year.

In September, the National Assessment of Educational Progress reported the biggest drop in 9-year-old reading performance in 30 years and the first-ever drop in math. The results erased decades of modest gains. Researchers have found that students lost the equivalent of one-third to one-half of a year in reading, and nearly twice that in math. And NWEA analysts have calculated that it will take students who started kindergarten in 2018 more than five years to make up the losses in reading achievement.

Researchers have found that students lost the equivalent of one-third to one-half of a year in reading, and nearly twice that in math.

Learning loss wasn’t evenly distributed, but was most severe among low-income and minority students and those whose schools were closed longest. Harvard University’s Tom Kane and his colleagues found that students who remained virtual during 2020-21 lost half of a year’s math learning, compared with 20 percent for students who were mostly in-person. Because schools in Democratic communities tended to stay closed longest, academic disruption was especially severe for low-income, minority kids in blue cities.

Two years of off-and-on schooling, intermittent isolation, and uncertainty also battered students’ emotional health and social well-being. Lockdown culture took a toll on kids already prone to spending too much time online and not enough connecting to peers and mentors. The surgeon general reported that the pandemic fueled increases in anxiety, depression, and other mental health disorders, while leading to a troubling jump in adolescent suicide attempts.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the pandemic has fueled an unprecedented exodus from public schools. Since 2020, public K-12 enrollment has declined by over 1.2 million students. In New York City, enrollment plunged from more than a million students in 2019 to 760,000 today.

Harvard public health professor Joseph Allen put it thusly last month: “Schools should be open. They should never have closed and should never close again. That was a mistake we will pay for over decades.”

Allen’s stance is actually close to the conventional wisdom at this point. In December of 2021, UNICEF and UNESCO concluded that public health officials had closed schools too hastily, kept them closed too long, and erred by closing them “as a first recourse rather than a last measure.”

Given all that, we should not forget that the teacher unions fought to prolong closures or that the Biden White House let the unions pressure the CDC to issue guidance making it tougher for schools to reopen.

But let’s turn to the more pressing question: What do we do now?

Tune Out the Noise: There’s been a lot of disruption, politics, and assorted nonsense of late. Public officials and school leaders need to eschew the sideshows and focus on getting kids back on track. Policymakers need to ensure that parents and educators have regular, reliable assessments that provide clear information on how students are doing and whether they’re making progress. School leaders need to open cafeterias; offer a full slate of after-school activities; give kids lots of personal and face-to-face time; and ensure that instruction is rigorous, engaging, and joyous.

There’s been a lot of disruption, politics, and assorted nonsense of late. Public officials and school leaders need to eschew the sideshows and focus on getting kids back on track.

Catch kids up: Students have suffered enormous learning loss, with the most vulnerable students experiencing the largest losses. Business as usual will not suffice. School routines need to be revamped in order to help students make up for the disruptions. This requires extended programming, more customized options, and intensive tutoring. School systems shouldn’t wait on the availability of local tutors but make aggressive use of digital tutoring providers with a track record of success. Addressing the inanities of remote learning will benefit from employing digital technology as a tool rather than a makeshift crutch.

Maintain transparency: Perhaps the one positive legacy of remote learning is the window it offered parents into schools and classrooms, into what their kids were learning and doing day-to-day. Through all of it, the thing I heard most frequently from parents may have been: “I had no idea.” No idea this teacher was so organized (or disorganized). No idea how much (or how little) learning occurred in a school day. Parents can feel walled off from what happens in school. The pandemic turned that inside out. Policymakers and educators should seek to maintain that connection.

Expand options: On the whole, parents were surprisingly good sports when schools shuttered in March 2020. Suddenly deputized as full-time teachers and tutors, many embraced homeschooling, explored learning pods, or turned to private schools and charter schools. Positive experience and gratitude for viable alternatives helped drive support for educational options to record highs, making 2021 the “Year of School Choice.” Public officials should keep working to expand charter schooling, vouchers, course choice, Education Savings Accounts, and more, with an eye to ensuring that all families have access to options that work for them.

Rewrite the pandemic playbook: In the years before COVID-19, public health officials came to embrace school closures as a default protocol. They assumed, based on instinct more than evidence, that schools would be super-spreaders and that the impacts on students would be manageable. Well, in the case of COVID-19, those assumptions proved disastrously wrong. Kids weren’t super-spreaders, were at minimal risk of serious illness, and the results of closure were devastating. Moreover, once schools were closed, it proved tough to reopen them. Going forward, pandemic planners need to set a much higher threshold for school closure.

In the course of the pandemic, states and communities have continued to fully fund schools that were often remote or part-time. Washington has showered schools with more than $200 billion in emergency federal aid. It’s time for schools to repay that goodwill by doing right by their students and for policymakers to ensure that we don’t repeat the mistakes we made. That won’t make up for the past few years, but it’ll be a start.

Frederick M. Hess is director of education policy studies at the American Enterprise Institute.