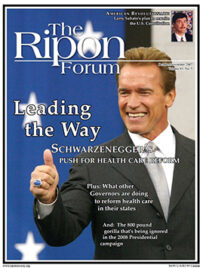

When Arnold Schwarzenegger introduced a plan this past January to reform California’s health care system, many people said there was little chance the plan would ever be approved. The issues were too formidable, they claimed; the political hurdles, too high to overcome.

Nine months later, the California Legislature is meeting in a special session to consider a revised version of the Governor’s plan. In looking at this revised proposal, the question that people should be asking is not whether it is a bridge too far politically, but rather, from the standpoint of good policy, whether it is a bridge to nowhere – an ill-conceived boondoggle that will cost too much and benefit too few.

The Governor has said he would “never close the door on anything,” and his revised plan is proof. Perhaps the biggest highlights are that it will cost $5 billion more than the plan introduced in January, and would rely on the lottery to fund health care. The Governor has said that funding to replace the lottery (truly reliable funding) would have to be set later.

Under the new plan, California’s workers, providers and individuals would still collectively strain to insure the state’s uninsured. All Californians would have to buy health insurance, insurers would be subject to guaranteed issue, and hospitals would still be under the gun for 4% of revenues, but only after a few stipulations from the California Hospital Association.

Perhaps the most significant of these stipulations is that hospital taxes would be kept separate from California’s general fund, and they would first go to increase Medi-Cal (Medicaid) payments to hospitals, and then to California’s uninsured.

Of course, these increases will be soaked up quickly. The Medicaid bureaucracy owes providers some $750 million in reimbursements. As a result, fewer doctors are participating. Two long-term care facilities have already filed suits against the state of California for not providing requisite Medi-Cal payments. In fact, Medi-Cal is second only to Texas for the highest Medicaid bill in the U.S., at $35 billion. Nevertheless, Governor Schwarzenegger wants to expand Medi-Cal and related programs for 900,000 more Californians.

Amidst protests from the California Medical Association, the governor’s new plan would no longer tax doctors 2%, but it would still tax employers — this time, based on payroll rather than the number of employees. If the business’ payroll is more than $100,000 and you don’t already offer health benefits, then you will pay a health care fee on a sliding scale from 0-4 %.

Perhaps the single best aspect of the Governor’s revised plan is to align state tax laws with federal laws by allowing Californians to make pre-tax contributions to Health Savings Accounts (HSAs), a kind of 401(k) for health. HSAs paired with high-deductible health plans will encourage Californians to save for health care rather than depending on employers or the government. More than a third of today’s HSA owners were previously uninsured.

Schwarzenegger is working towards a finance proposal for the November 2008 ballot. If he really does intend to “keep the door open” through this process, then he should follow the lead of State Senate Republicans to fix, rather than force, insurance.

The state should reform “scope of practice” laws affecting nurse practitioners, who are qualified to provide basic, affordable health care. This would allow Californians to take advantage of retail-based “convenient clinics,” a competitive answer to emergency rooms for basic services. Also, costly government-mandated health benefits force Californians out of individual insurance. Insurers need to compete with each other to meet the needs of individual patients.

These incremental, common sense steps may not provide for dramatic headlines. But they will provide people with a bridge that leads to a better health care system – a system that is defined not by government taxes or mandates, but by choice, quality and cost-effective care.

Diana Ernst is a Health Care Policy Fellow at the Pacific Research Institute.