As veterans of an eight-year struggle to reimagine and reinvent the Democratic Party, we look at today’s Republicans with a wry sense of recognition. Much of what we wrote about our party a quarter of a century ago applies with only minor modifications to the contemporary GOP: an unattractive message, outdated policies, adverse demographics, and a fatally flawed political strategy, among other similarities. Now as then, the losing party is talking to itself more than it is listening to the people. Now as then, a party wrestling with defeat is hampered by an entrenched base that resists change and punishes those who try to bring it about.

In our experience, successful reform of a political party requires a number of difficult steps: diagnosing the party’s ills; discarding backward-looking policies; restating the party’s principles in terms that attract rather than repel skeptics; and crafting proposals that address the broad population’s problems and concerns, not just those of core supporters. Reform requires, as well, an organization that serves as a focal point for reformers, helps incubate new ideas, and leads the battle for their adoption by the party. And it requires, finally, standard-bearers who understand the reform agenda and can explain it clearly to party leaders, to the rank and file, and ultimately to the entire electorate. Money, technology, and tactics matter, of course, but only within a broader reform strategy.

Judged against this template, the reform of the Republican Party is taking, at most, its first halting steps. A politics of nostalgia still attracts too many Republicans, for whom “Back to Reagan” is a mantra that soothes and cures. But we are as far away from the end of the Reagan Administration as Democrats were from FDR at the beginning of the Nixon Administration. Reaganism applied conservative principles to a specific historical situation. If Reagan reappeared today, his principles would be the same, but many of his proposals would not. As long as Republicans imagine that the party’s 1980 platform will solve either today’s public problems or their own political problems, they’ll continue to struggle.

Reagan was to Democrats as FDR was to Republicans — a great communicator whose rhetorical gifts sugar-coated a pill that they believed the people otherwise would not have swallowed.

Another popular but counterproductive tendency is to blame the messenger rather than the message. Throughout the New Deal, Republicans convinced themselves that Franklin Roosevelt was a snake charmer who had bewitched the people and that all would be well once he passed from the scene. It took Harry Truman’s unexpected victory over Tom Dewey to convince Republican leaders that their problems went deeper, setting the stage for Eisenhower’s successful battle against Robert Taft. Ike’s program of “Modern Republican- ism” ended the party’s battle against the New Deal and restored it as a serious national competitor.

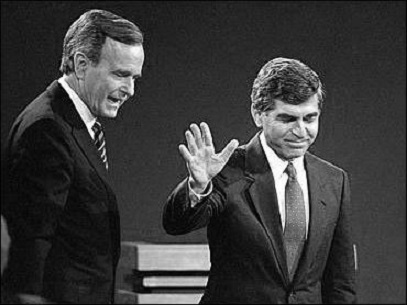

Reagan was to Democrats as FDR was to Republicans—a great communicator whose rhetorical gifts sugar-coated a pill that they believed the people otherwise would not have swallowed. Not until Michael Dukakis’ startling defeat at the hands of George H.W. Bush did Democrats begin to realize that their problems might be more than cosmetic.

Once again, the same drama is playing itself out. Many Republicans (including their presidential nominee) believed up to Election Day that victory over Obama was assured. Recovery from recession was slow; unemployment remained high; household incomes were depressed; the President’s approval ratings hovered around 50 percent. As the returns rolled in, recriminations began: The wealthy Mitt Romney was miscast in hardscrabble populist times; he stood mute in the face of the Obama campaign’s summer onslaught; and he destroyed himself with his “47 percent” video, the economic equivalent of Todd Akin’s remarks on rape.

There is some truth to all this, of course, but it was mostly a diversion from the basic point: The Reagan agenda was played out, and the Tea Party’s Wahhabi-style drive to restore pure, uncompromised conservatism had led the party away from, rather than toward, an electoral majority. Tacitly acknowledging this reality, party leaders began to think out loud. While a report from the Republican National Committee focused mainly on mechanics, its authors forthrightly stated that “America looks different” and drew some obvious policy implications. In particular, they stated, “We must embrace and champion comprehensive immigration reform. If we do not, our Party’s appeal will continue to shrink to its core constituencies only.” The authors also acknowledged the force of generational change: “[T]here is a generational difference within the conservative movement about issues involving the treatment and the rights of gays—and for many younger voters, these issues are a gateway into whether the Party is a place they want to be.”

Not until Michael Dukakis’ startling defeat at the hands of George H.W. Bush did Democrats begin to realize that their problems might be more than cosmetic.

A subsequent report from the College Republican National Committee (CRNC) underscored this point. In findings based on two commissioned surveys and other data, the report documented the sizeable gap between young voters’ perceptions of the Republican Party and their own preferences and beliefs. While not ignoring problems rooted in technology and branding, the report paid the most attention to policy-based difficulties. While young voters’ reservations about the Republican Party begin with social issues such as same-sex marriage, they hardly end there. These voters also believe that the wealthy should pay higher taxes; that Republicans don’t want to help them pay their student loans; that reducing the size of “big government” is much less important than attacking entrenched interests on a broad front; that they will be better off under Obamacare; that the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan were mistakes that the United States should not repeat; and that, along with same-sex marriage, immigration reform functions as a “gateway issue.” Even when they disagree with Obama’s policies, most young voters at least give him credit for trying to fix problems, while Republicans are seen as mostly negative, often harshly so.

Toward the end of the CRNC report, the authors implicitly question their party’s dominant narratives. Their most recent commissioned survey com- pared a wide range of broad narratives that Republican candidates could use. The winners among young voters: creating jobs and economic growth, tackling the tough problems that will face the next generation, and giving hardworking people the opportunity to advance. The losers: protecting Americans’ liberty and the principles of the Constitution, promoting liberty and reducing the role of government, and protecting families and core American values. While the authors don’t spell it out explicitly, the conclusion is inescapable: The messages that have dominated the Republican Party since the beginning of the Obama Administration are turning off young adults. (The attack on big government is especially unpopular with Hispanics.) To summarize the report in language that its authors would surely reject, George W. Bush was more right than wrong, and the Tea Party is more wrong than right.

Reform on the Horizon?

In this context, it is hardly surprising that the party’s leading thinkers are beginning to weigh in. In an article entitled “Reaganism After Reagan” published in February 2013, National Review’s Ramesh Ponnuru commented, “Today’s Republicans are very good at tending the fire of Ronald Reagan’s memory but not nearly as good at learning from his successes. They slavishly adhere to the economic program that Reagan developed to meet the challenges of the late 1970s and early 1980s, ignoring the fact that he largely overcame those challenges, and now we have new ones.” Ponnuru concluded with a flourish that verged on heresy: “In his first Inaugural Address, Reagan famously said that ‘government is not the solution to our problem; government is the problem.’ The less famous yet crucial beginning of that sentence was ‘in our present crisis.’ The question is whether conservatism revives by attending to today’s conditions, or becomes something withered and dead.”

Once again, the same drama is playing itself out. Many Republicans (including their presidential nominee) believed up to Election Day that victory over Obama was assured.

If “Back to Reagan” won’t do as a strategy and budget cutting has hit a political wall, what comes next? Since Romney’s defeat, several strands of conservative reform have emerged and gotten a new hearing. Rand Paul is trying to move libertarianism into the Republican mainstream, and recent controversies over drones and surveillance have given him the opportunity to enhance his national visibility. For conservatives, the road to reconnecting with young adults starts with libertarian-leaning stances on social and national-security issues.

Another brand of conservative reform tilts toward economic populism. A large piece of the Republican base has only modest levels of education and income. Mitt Romney had nothing to say to them, which helps explain why mil- lions of white voters stayed home last November. Back in 2008, however, two young conservatives, Ross Douthat and Reihan Salam, had already diagnosed the problem. In Grand New Party: How Republicans Can Win the Working Class and Save the American Dream, they advocated the selective use of government to reweave the fabric of civil society and address the neglected economic needs of downscale Americans. Former Minnesota Governor Tim Pawlenty took up their cause under the banner of “Sam’s Club conservatism” during his brief 2012 campaign, but he could not channel the anger of Republican primary voters, whose antipathy to Obama spilled over into a general anti-government stance. Pawlenty’s candidacy quickly collapsed, but the woes of the working class remain, offering opportunities to conservative reformers willing to chal- lenge entrenched economic orthodoxies.

A third strand of conservative reform, mainstream rather than populist, tries to build on what George W. Bush got right. In March 2013, two veterans of the Bush Administration, Peter Wehner and Michael Gerson, published a lengthy essay, “How to Save the Republican Party—A Five-Point Plan.” They began by noting key shifts in the country since Reagan: Demographic changes were working in favor of Democrats, and the end of the Cold War reduced the credibility of the classic Republican “tough on defense” stance. Echoing Ponnuru, they commented: “[I]t is no wonder that Republican policies can seem stale; they are very nearly identical to those offered up by the party more than 30 years ago. For [today’s] Republicans to design an agenda that applies to the conditions of 1980 is as if Ronald Reagan designed his agenda for conditions that existed in the Truman years.”

Gerson and Wehner went on to propose new approaches in five areas: focusing on the economic concerns of working- and middle-class Americans; welcoming rising immigrant groups; pushing back against hyper-individualistic libertarianism by demonstrating the party’s commitment to the common good; engaging social issues in a manner that is aspirational rather than alienating; and harnessing their policy views to the findings of science. While they aren’t always clear about the specific policy implications of these approaches, they do endorse breaking up the big banks and enacting comprehensive immigration reform. Describing opposition to gay marriage as a “losing battle,” they note tartly (and correctly) that “it is heterosexuals, not homosexuals, who have made a hash out of marriage,” and they suggest that Republicans and conservatives might more usefully focus on strengthening marriage in all its forms.

There’s no substitute for a leader with the guts to break with outdated party orthodoxy, as Clinton did on trade, fiscal policy, welfare, and crime, among other issues.

Gerson and Wehner offered not only policies, but a theme as well: “The Republican goal is equal opportunity, not equal results. But equality of opportunity is not a natural state; it is a social achievement, for which government shares some responsibility. The proper reaction to egalitarianism is not indifference. It is the promotion of a fluid society in which aspiration is honored and rewarded.”

If there were a political equivalent of intellectual property, we could sue for patent infringement, because these sentiments can be found, nearly verbatim, in numerous DLC documents from the late 1980s on. The resemblance is no coincidence: Along with Tony Blair’s New Labour, Gerson and Wehner cite the DLC and Bill Clinton as their models of successful party reform. Not surprisingly, we think they’re on to something.

Despite this intellectual ferment, the transformation of the Republican Party has barely begun. There’s no substitute for a leader with the guts to break with outdated party orthodoxy, as Clinton did on trade, fiscal policy, welfare, and crime, among other issues. And he did more than that: In the famous Sister Souljah episode, he spoke out against a tendency in the party’s base that crossed the line from protest to extremism. Mitt Romney and the other contenders for the 2012 Republican nomination had numerous opportunities to do just that, and they ducked them all. The incredible statements about women and rape by two Republican Senate candidates could have served as a Sister Souljah moment for Romney. But rather than using these to mount a full-throated pro- test against extremism in the Republican Party, he offered a mild rebuke that did nothing to undo the damage or to change the trajectory of the campaign. As long as aspirants for party leadership flinch from confronting their angry base, the American people will continue to see Republicans as an uncompromising, uncaring, and retrograde force.

And until party intellectuals are willing to go beyond policy prescriptions and call extremism by its rightful name, it is unlikely that any candidate will be willing to do so. The phrase “liberal fundamentalism” made us few friends a quarter of a century ago, but it was necessary for us to say it. We’re waiting for our counterparts among today’s Republicans and conservatives to do the same.

There’s something else missing as well – a focal institution that brings reformers together to craft new policies and the political strategies needed to make them effective, first within the party, and then for the entire country. So far, the Republican intellectuals seem to operate in a vacuum. They have little formal connection to the party’s elected officials or its organizations. It will be a sign of seriousness when Republican dissidents are willing to devote their energies and resources to creating an organization devoted to party reform and protecting it from being strangled in the cradle, as the defenders of entrenched arrangements will surely try to do. If Republican leaders and candidates try to improve their party’s fortunes without changing its orientation, they will surely fail.

Much is at stake, not just for Republicans, but for the entire country. The polarization of our party system has thwarted action on critical challenges and has exacerbated public mistrust. As long as our parties remain at roughly equal strength, our institutions can only work when adversaries are willing to debate fiercely—and then reach honorable compromises. A Republican Party dominated by a new generation of reform-minded conservatives who care more about solving problems than scoring points would be a huge step toward restoring a federal government that can govern.

William A. Galston is the Ezra K. Zilkha Chair and Senior Fellow in the Governance Studies Program at the Brookings Institution and College Park Professor at the University of Maryland School of Public Policy. From 1993 to 1995, he served as Deputy Assistant to the President for domestic policy. Elaine C. Kamarck is a Senior Fellow in the Governance Studies Program and the Director of the Management and Leadership Initiative at Brookings. As a senior staffer in the Clinton White House, she created the National Performance Review, the largest government reform effort in the last half of the twentieth century. This is an excerpt of an essay that originally appeared in the Fall 2013 edition of Democracy: A Journal of Ideas (www.democracyjournal.org).