On August 18, 1988, on the last night of the Republican National Convention, Vice President George H.W. Bush stepped to the podium at the Louisiana Superdome and accepted his party’s nomination for President.

Penned by speechwriter Peggy Noonan, Bush’s acceptance address is an eloquent accounting of the Reagan Administration’s successes, the candidate’s credentials and his contrasts with his opponent, Massachusetts Governor Michael Dukakis.

The most memorable line from that speech, “Read my lips: no new taxes,” helped get Bush elected a few months later. It also established a litmus test for many candidates in many elections to come.

But it’s not that simple — especially now.

To be sure, with the economy struggling, tax receipts falling and federal deficits soaring, there’s more pressure than ever for government cost-cutting. Yet in such an environment, savvy voters and citizens are asking not only, “Will you hold the line on taxes?” but also, “How?”

The devil is in the details, of course, but I will suggest to any candidate or officeholder—Republican, Democrat or Independent — that one loud and clear answer has to be “government reform.”

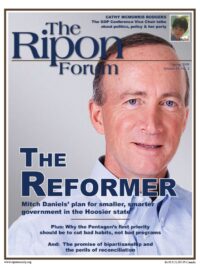

In June 2007, Indiana Governor Mitch Daniels called me. He said he wanted to work on the how-will-we-lower-taxes question by finding innovative ways to reduce local government costs.

At the time, Daniels was under tremendous pressure to address a property tax crisis that had been brewing for decades. Daniels had plans for addressing the tax issue, but he knew he couldn’t cut and/or cap property taxes — a primary funding source for local government —without simultaneously addressing some of the antiquated jurisdictions, structures and mandates that render local government inefficient and ineffective in a modern era.

Daniels knew he couldn’t cut and/or cap property taxes without simultaneously addressing some of the antiquated jurisdictions, structures and mandates that render local government inefficient and ineffective in a modern era.

On the phone that day, Daniels asked if my colleagues and I would serve as researchers and principal staff for a bipartisan commission on local government reform.

He said he wanted the commission to review the best government reform ideas from Indiana and elsewhere — ideas that were new and ideas that had been on the table for decades.

He said he wanted all things considered — no sacred cows.

He said he wanted the commission to consider ways not only to reduce local government costs, but also to make local government more understandable and transparent.

And he wanted it fast — within a matter of months — so the Legislature could consider the commission’s recommendations during its 2008 session.

I asked who he had in mind to head the commission. The governor gave me two names.

The first was the sitting chief justice of the Indiana Supreme Court, Randall Shepard, a Republican.

The second told me Daniels was dead serious about bipartisan reform: He wanted his predecessor — the sitting governor he defeated in the 2004 election — Democrat Joe Kernan.

Recognizing how savvy and gutsy that call was, I said yes.

A Blueprint for Reform

The Kernan-Shepard Commission added five other members — a former Republican secretary of state, a former Democratic state senator, the former president of Indiana University, a retired corporate executive and a former county government official.

For six months, Commission members reviewed and debated years worth of existing research — data, academic studies, white papers, think-tank reports, past study committee recommendations, best practices from other states and thousands of ideas submitted by members of the public.

During the Commission’s review process, representatives of various interests—objective and vested — stated their cases. Citizens participated in public forums statewide and sent suggestions via a dedicated Web site. Individual commissioners dug deep into particular areas of interest and reported their findings.

In the end, the Commission produced a report called “Streamlining Local Government: We’ve got to stop governing like this.” The report can be found at http://indianalocalgovreform.iu.edu/

The report contains 27 recommendations designed to reduce the cost and complexity of local government in Indiana. The ideas touch townships, towns, cities, counties, school boards, libraries, public safety departments, elected officials, appointed officials and more.

All the ideas reflect a set of guiding principles agreed upon by the commissioners. These principles suggest that local government should:

- Be simpler, more understandable and more responsive.

- Be more transparent, allowing citizens to better understand whom to hold accountable — whom to thank or blame — for decisions, actions and spending.

- Drive real cost savings … through the reduction of local government layers and the adoption of other cost-saving measures.

- Be flexible enough to accommodate different kinds and sizes of communities and an evolving definition of community.

- Focus on long-term solutions that not only consider immediate needs, but also provide for future efficiency and growth.

- Create a more equitable distribution of services and responsibility for funding them.

- Reduce the number of local officials and local units of government.

- Allow only elected (not appointed) officials to approve taxes and debt.

- Limit appointed officials to administrative responsibilities, and ensure professional qualifications and performance standards where appropriate.

This wasn’t rocket science. Some of the ideas had been around for decades. Indeed, the most comprehensive reform recommendations were produced in 1935 for Democratic Gov. Paul V. McNutt. But here in the Hoosier State, structural local government reform has never been enacted.

The “never enacted” part concerned Commission members most of all. As Kernan and Shepard wrote in their introduction to the Commission’s report, “The transformation we propose will be disruptive, even painful, in the short run. Many who have vested interests in the status quo will resist these changes with great vigor.”

A wiser prediction has rarely been writ. Suffice it to say that the welcome for Kernan-Shepard’s proposed reforms has been cool, at best.

To be sure, Governor Daniels embraced all but a few of the recommendations with open arms. Business and opinion leaders (including many newspaper editorial boards) endorsed the proposals enthusiastically. And a grassroots advocacy group emerged to champion the cause.

But the vested-interest lobby turned out in full regalia in opposition. So while a few proposals have been enacted, most have died an ignoble death in two consecutive legislative sessions.

The Rewards of Leaner Government

As a public policy analyst, I’ve studied which recommendations have survived, which have struggled, and why. In the process, I’ve gleaned lessons and identified opportunities for public officials in Indiana and beyond.

First, I’ve learned that the easiest way to push reform is to act in response to crisis — real or perceived.

As the Kernan-Shepard Commission convened, Indiana found itself in property tax chaos. This triggered screaming headlines and mass protests. It’s no surprise, therefore, that the most significant Kernan-Shepard reform to date involves assessors.

Advice to would-be reformers: Follow White House Chief of Staff Rahm Emanuel’s Rule One: “Never allow a crisis to go to waste.”

I’ve also learned some key reasons why government reforms are about as popular as root canals:

- Fear of confrontation. Most people prefer to avoid confrontation. Elected officials are no exception. So for your average state senator or representative, it’s understandably anxiety-inducing to head home from the Capitol to tell Frank the sheriff, Mabel the auditor, Bob the commissioner, Suzie the trustee or Sam the school board member that you’re eliminating their elected position in the interest of a newfangled model.

- Fear of upending the political farm system. Traditionally, lower-level elective offices have fed both parties. The county council member becomes a state senator. The state representative becomes governor. The council member becomes mayor. What’s more, precincts, wards and townships are traditional breeding grounds for voter turnout. So the parties are understandably reluctant to tinker. They think this would be akin to Major League Baseball abandoning single-A ball clubs.

- Fear of losing local control and accountability. Even if folks don’t understand what the auditor, assessor, coroner or commissioner do exactly; and even if they can’t name the individuals elected to these offices; they’re reluctant to cede the ability to “throw the bum out” to an elected mayor or county executive further up the political ladder.

- Fear of increased accountability. Increased transparency and accountability can cut both ways. Some elected executives grow frustrated when they’re blamed for tax increases over which they have no authority—increases imposed by appointed boards and commissions, for example. On the other hand, there are executives who like being able to shift responsibility to other bodies. That way, they can say, “I didn’t do it. The board did it.” Under Kernan-Shepard, there’d be no hiding, because only elected officials could increase a tax.

So given these inherent reasons to resist, why do I see political and public-policy opportunity in government reform?

The no-new-taxes mantra is as relevant today as when George H.W. Bush uttered it. But even the best leaders can’t perpetually do more with less if they’re bound by silos and boxes invented decades or centuries ago.

Boundaries drawn in the horse-and-buggy era make no sense in the Age of Cyberspace. Procedures developed before the advent of rubber stamps are nonsensical in an era of e-filing. Elective offices established at a time when everyone knew everyone else in a small town make no sense in a century when most folks can’t name their senator, congressman or governor.

Yet that’s what we impose on our local governments and the elected officials chosen to run them.

Boundaries drawn in the horse-and-buggy era make no sense in the Age of Cyberspace. Procedures developed before the advent of rubber stamps are nonsensical in an era of e-filing.

Wouldn’t it be better to give fewer, more-visible elected officials the power to hire and fire the professionals they need?

Wouldn’t it be better to provide those professionals with adequate resources, systems and structures to do more efficient, cost-effective, visible, understandable and accountable work?

Wouldn’t it be better to actually know what the leaders were doing and know whom to remove from office if it wasn’t done well?

Wouldn’t the citizens and voters be happier if fewer of their tax dollars were spent with a higher level of accountability?

Wouldn’t they be better informed if they had fewer layers to watch and comprehend?

Wouldn’t they be more likely to vote for elected officials and the protégées who emerged from a more-effective government?

Wouldn’t our political parties be stronger if they showed they could do more for less?

Wouldn’t the idealistic young people in my university’s classrooms rather work in governments that were more modern, professional and respected?

If we continue to avoid confrontation and retain the status quo of outdated, outmoded local government, it will be impossible for candidates to say “read my lips: no new taxes” with any credibility.

If we continue to avoid confrontation and retain the status quo of outdated, outmoded local government, it will be impossible for candidates to say “read my lips: no new taxes” with any credibility.

The status quo is a recipe for broken promises, perpetual public-policy failure and proverbial political disrespect. Neither the citizens nor the parties win. Government reform requires courage and confrontation. But for leaders willing to act, the rewards will be rich and well-deserved.

Just ask Mitch Daniels. His favorability rating now stands at 68 percent. This is 10 points higher than it was last September. So while the vested interests may not like the reforms he is pursuing, those proposals have certainly not done him any damage with his most important constituency — the people of the Hoosier State.

A former Indianapolis deputy mayor, John Krauss directs the Indiana University Public Policy Institute and its Center for Urban Policy and the Environment. The Institute is part of IU’s School of Public and Environmental Affairs, where Krauss is a clinical professor. He’s also an adjunct professor of law at the Indiana University School of Law-Indianapolis.