The U.S. Senate is in the midst of a raucous debate on an issue that the U.S. Congress avoids until it has absolutely no choice but engage it — reforming the nation’s immigration laws.

The legislative vehicle is a lucid if imperfect bipartisan compromise negotiated painstakingly over countless hours of face-to-face meetings and has been denounced by both extremes.

The proposed bill is a radical departure from the present system, put into place over 40 years ago — a vastly different political and economic era. It challenges Democrats and their allies by giving them their number one immigration reform goal: a legalization program that offers virtually every illegally resident person who was here on January 1, 2007, a nearly automatic temporary work permit lasting for 1 months and the opportunity to gain permanent legal status (a “green card”) between eight and 13 years later.

In the interim, between three and four million relatives of U.S. citizens and permanent residents who had been languishing on massive waiting lists would get their green cards — hence honoring the political mantra that legalizing immigrants would have to wait their turn for green cards until the infamous “queue” empties out.

In return — a “trade off” to many serious advocates but a “Faustian bargain,” and worse, to many of the Democratic party’s more unyielding constituencies — enforcement would be ratcheted up enormously and family relationships beyond the nuclear families of U.S. citizens and U.S. permanent residents (albeit in highly restricted ways) would no longer gain automatic if greatly delayed access to green cards. Instead, such relatives would need to negotiate successfully a points-based merit system that awards permanent status only to those with the “right” occupational characteristics, significant labor market experience and connections in the U.S., education, and English. Only if applicants earn 55 out of 100 possible points can they gain access to up to 10 bonus points for their family ties.

Finally, Democrats and a variety of stakeholders are asked to agree to several temporary worker programs mostly for low skill/wage work in configurations intended to prevent them from developing roots in the U.S. and explicitly prohibit them from gaining green cards automatically — unless, of course, they can earn their way to such status through the points based system.

If the Senate bill presents a fundamental challenge to Democrats, its Republican authors face a much uglier challenge: a total and loud renunciation by some of their colleagues and the more extreme wing of the party’s chattering class. Those ideologues’ brightest line in this debate — “no amnesty” — has been breached in the fullest and most direct way. Vigorous explanations by those who are committed to the bill’s approach, which includes the President, that the bill is not an amnesty is merely throwing fuel to an already raging fire.

So, how should reasonable people regardless of party affiliation think of this bill? First, the compromise bill has a deep inner logic and meets a crucial political requirement — mainly, that only a bipartisan bill that “draws some blood” from both sides can pass this or virtually any Congress absent some truly dramatic political realignment.

Second, the bill gets many more things right than it gets wrong. Foremost among the things it gets right is that legalization is just as the President says: an imperfect but pragmatic response to a problem that is simply too massive and too embedded into our society and economy to address with the musings of the “just say no” crowd. But this bill gets a whole raft of other good governance ideas essentially right — most notably, by reflecting the key lessons from the 1996 legislation that all sides criticize so fluently.

- Enforcement is front and center. In fact, by requiring that a variety of very robust triggers be in place before legalization commences, and considering the massive control and enforcement efforts already in place, the demand of so many Americans and Republican legislators that enforcement precede legalization is being met — period.

- The legalization date is virtually current and the program’s initial requirements are clear and intended to get full participation. That means that, taken together with the enforcement build up, there will be no nucleus of illegally resident persons left behind around whom the next wave of illegal flows will be built. It also means that by thus reducing the proverbial haystack of the unauthorized, the government can deploy its resources to finding the “needles” that should be of concern to us all.

- Finally, the bill widens and deepens the channels for legal immigration dramatically — and in line with most estimates of the size of the “demand” for new workers. Does this all mean that this is the exact bill that can take us to the promised land of good public policy and better governance? Not really. The bill’s blemishes are many and they will need to be fixed through amendments and in the negotiations with the House of Representatives. Three areas are in need of particular attention.

First, the point system is inflexible — thus missing a key reason why point systems are being adopted by so many high and even middle income countries. As conceived, it cannot be changed for at least five years after it takes effect, virtually eons in the fast changing U.S. (and global) economy. This means that some of those who meet the points requirements will not meet true labor market needs. Furthermore, the bill takes away from U.S. employers the ability to attract the best workers anywhere by offering them a U.S. green card at a time where the competition for the most skilled and talented is becoming intense. Why hobble our most competitive firms when one of the proposed bill’s basic thrusts is to align our immigration system better with our economic interests?

…only a bipartisan bill that “draws some blood” from both sides can pass this or virtually and Congress absent some truly dramatic political realignment.

Second, some of the restrictions on family go beyond the stated aim of reducing chain migration and contravene most common sense principles of fairness and family unity — even if they are in the bill primarily in order to be traded for other things. To stand on principle on this issue, Republicans must do two things. Allow amendments that will support the unification of nuclear families, period. That means that green card holders must be able to bring their spouses and minor children with them or reunify with them after the fact. This makes sense demographically (we will need their youth) while avoiding starting a new backlog of those whose (re)unification is most consistent with what we stand for when we speak of family values. In addition, family relationships must be given more points in the point system while the attributes they bring — hard work and entrepreneurship — are properly recognized.

The final area that needs fixing, the proposed temporary program, will need help from both sides of the aisle. Democrats should stop trying to kill it or relegate it to numerical insignificance. It is an essential part of overall reform if we do not want to have another ugly standoff about immigration a few years from now. They should focus instead on the terms and conditions under which these workers will be employed and on making the point system “friendlier” to them. Republicans, in turn, should drop their “temporary is temporary” mantra.

The objective of reform must remain focused on legality, order and competitiveness — and those who play by the rules and can demonstrate that they can make long term contributions to our country should be allowed to earn their way to green cards through a more thoughtful allocation of points.

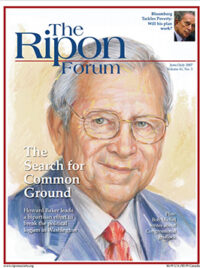

Dr. Demetrios G. Papademetriou is co-founder and President of the Migration Policy Institute, a Washington-based think tank dedicated exclusively to the study of international migration.