The news that the national economy may be out of deep water couldn’t be more welcome. But many states are still in danger of drowning. Unemployment, foreclosures and Medicaid spending are already hitting the states hard. And there’s another significant bill coming due: public pensions and retiree health care.

The news that the national economy may be out of deep water couldn’t be more welcome. But many states are still in danger of drowning. Unemployment, foreclosures and Medicaid spending are already hitting the states hard. And there’s another significant bill coming due: public pensions and retiree health care.

According to a recent study by the Pew Center on the States, there is a $1 trillion gap between the amount of money states have set aside to pay employees’ retirement benefits and the $3.35 trillion price tag of those promises to current and retired workers. This estimate is conservative: Since most states assess their retirement plans on June 30, the analysis does not fully reflect the severe investment declines in the second half of 2008 before the modest recovery of 2009. As of fiscal year 2008, states were short $452 billion of the $2.8 trillion needed to pay their pension bill. That gap will continue to grow as states fully account for the dramatic investment losses in 2008 and 2009—leaving states struggling to fund their pension plans. Experts, including the U.S. Government Accounting Office, recommend that any state should keep its pensions 80 percent funded or higher. But 21 states are currently below that level, and eight—Connecticut, Illinois, Kansas, Kentucky, Massachusetts, Oklahoma, Rhode Island and West Virginia—are short of their liability by more than one-third.

As of fiscal year 2008, states were short $452 billion of the $2.8 trillion needed to pay their pension bill. That gap will continue to grow as states fully account for the dramatic investment losses in 2008 and 2009—leaving states struggling to fund their pension plans.

The situation for retiree health care and other non-pension benefits (such as life insurance) is even more troubling. The total liability for these programs—$587 billion—is substantially smaller than the total pension bill. But almost 95 percent of it is unfunded, and that accounts for more than half of the trillion dollar gap.

Some states are just starting to save for their retiree health care liabilities, largely because of accounting changes recommended by the Governmental Accounting Standards Board, which were released in 2004 and went into effect in 2006. But the 50-state average for savings toward health care liabilities is only about 7 percent of total costs, and 40 states fall below that very modest bar. Twenty states have nothing saved to cover health care and other non-pension commitments. In general, states continue to fund retiree health care on a pay-as-you-go basis. For states offering minimal benefits, this may cause little problem. But for those that have made significant promises, the future fiscal burden will be substantial.

The broader economic effects also will be considerable. How well states manage their employee retirement costs will play a large role in determining how much money is available for other priorities. Every dollar fed to that growing liability is a dollar that cannot be used for education, public safety or other needs. Left unchecked, this problem will become a crisis for future generations. But it already poses a serious fiscal challenge for today’s taxpayers. The share of state budgets that goes to meet these costs is already sizable. In 2008, states needed nearly $108 billion to pay their full required contributions for pensions and retiree health care. To put that figure in perspective, states spent about $152 billion that year on higher education.

How did this happen? Economic recessions and investment losses played a role. But the trillion dollar gap primarily reflects states’ lack of discipline. Over the last 10 years, many states shortchanged pension plans in both good times and bad. Too often, policy makers kicked the can down the road, increasing benefits without considering the price tag or failing to make their required annual payments. Like a credit card holder who makes a minimal or no monthly payment while adding new purchases, states have built up a large balance that becomes harder to pay off with each passing day. And the larger the unfunded liability, the higher the annual cost.

Contrasting New York and New Jersey illustrates how poor management affects the bottom line. In 2002, these neighbors both had fully funded pension systems. Over the next six years, New York made its required annual contributions, but New Jersey did not. As a result, New Jersey’s cost burden for 2008 was $1 billion more than New York’s, even though New Jersey’s total pension liability was $15 billion less than the Empire State’s.

The results of this decade of irresponsibility are startling. In 2000, just over half the states had fully funded pension systems. By 2006, that number had shrunk to six states. By 2008, only four states—Florida, New York, Washington and Wisconsin—could make that claim.

This challenge is dire, but can be solved. There are three actions states can take. First, they can fully and regularly fund their annual required contribution for retiree benefits; second, they can reduce their liability by cutting benefit levels, sharing costs and more of the investment risk with employees and taking other measures, such as raising the retirement age; and third, they can improve how retirement systems are governed and how pension fund investments are overseen and managed.

There are three actions states can take. … These fixes won’t deliver dramatic results overnight—but even small changes made today can have a big impact in the future.

These fixes won’t deliver dramatic results overnight—but even small changes made today can have a big impact in the future. For example, Minnesota’s 1989 decision to raise its retirement age by one year has saved taxpayers $650 million over the last two decades.

Although changing benefits can be very difficult, there are states that have done so. For example, early this year, state leaders in Vermont wanted to make dramatic cuts in pension benefit levels. The Vermont teachers union bitterly opposed this, but also conceded that the status quo was unsustainable. A compromise was reached in January 2010 that will result in most teachers working additional years and making higher contributions to the pension fund but receiving a larger pension check on retirement. The state will initially save $15 million a year, or about 10 percent of Vermont’s current budget shortfall. This deal was possible because concerns related to the retirement security of workers were addressed along with the need to control costs.

A similar story played out in Nevada last year when different sides of the political spectrum gave ground in a debate over retiree benefits and a severe state budget gap. The Chamber of Commerce dropped its longstanding support of a defined contribution plan for public sector employees and endorsed a broad tax increase package to help balance the state budget. Republican lawmakers said they would support a tax increase but only if Democrats agreed to tighten the pension system for new hires. The budget passed. Under the reform, new workers cannot begin receiving benefits until age 62, while current employees can retire at 60 with 10 years’ service or at any age with 30 years. The plan also reduces the cost-of-living adjustment and the multiplier used to calculate benefits after an employee retires.

Steep pension fund investment losses in the past two years have made it clear that states cannot sit back and hope the market will deliver enough returns to close the trillion dollar gap. Meanwhile, swelling numbers of baby boomers are nearing retirement, and will live longer on average than earlier generations. The writing is on the wall: Ignoring the problem in the face of these converging factors will ensure far more serious budget trouble for states in the future.

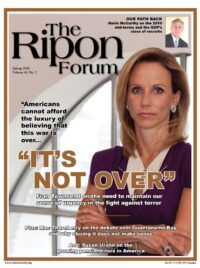

Susan K. Urahn is the Managing Director of the Pew Center on the States. The Pew Center on the States’ report “The Trillion Dollar Gap” is available at: www.pewcenteronthestates.org/trilliondollargap