We were lucky. The Cold War should not have ended so peacefully. Great powers rarely cede their empires without an ensuing great power war. Neither do they typically transform their very social and political superstructures without mass violence. History offers few if any other examples where both occurred simultaneously, none with 20,000 nuclear weapons in the mix.

We recall the heady events that marked the Cold War’s end most often as a story of crowds, forgetting much of the anxiety. Time and again, from Budapest to Leipzig, Prague to Kiev, and ultimately Berlin to Moscow, crowds of Eastern European citizens, ordinary people confronting extraordinary times, demanded reforms their governments could in no way endorse and still survive. The volatility of these moments cannot be overstated. Any of those aforementioned crowds, or police ordered to stop them, could have sparked a conflagration that consumed the continent. The June, 1989, crackdown that transformed Tiananmen from a place to an event in global consciousness offers a mere taste of what, thankfully, never occurred in Europe.

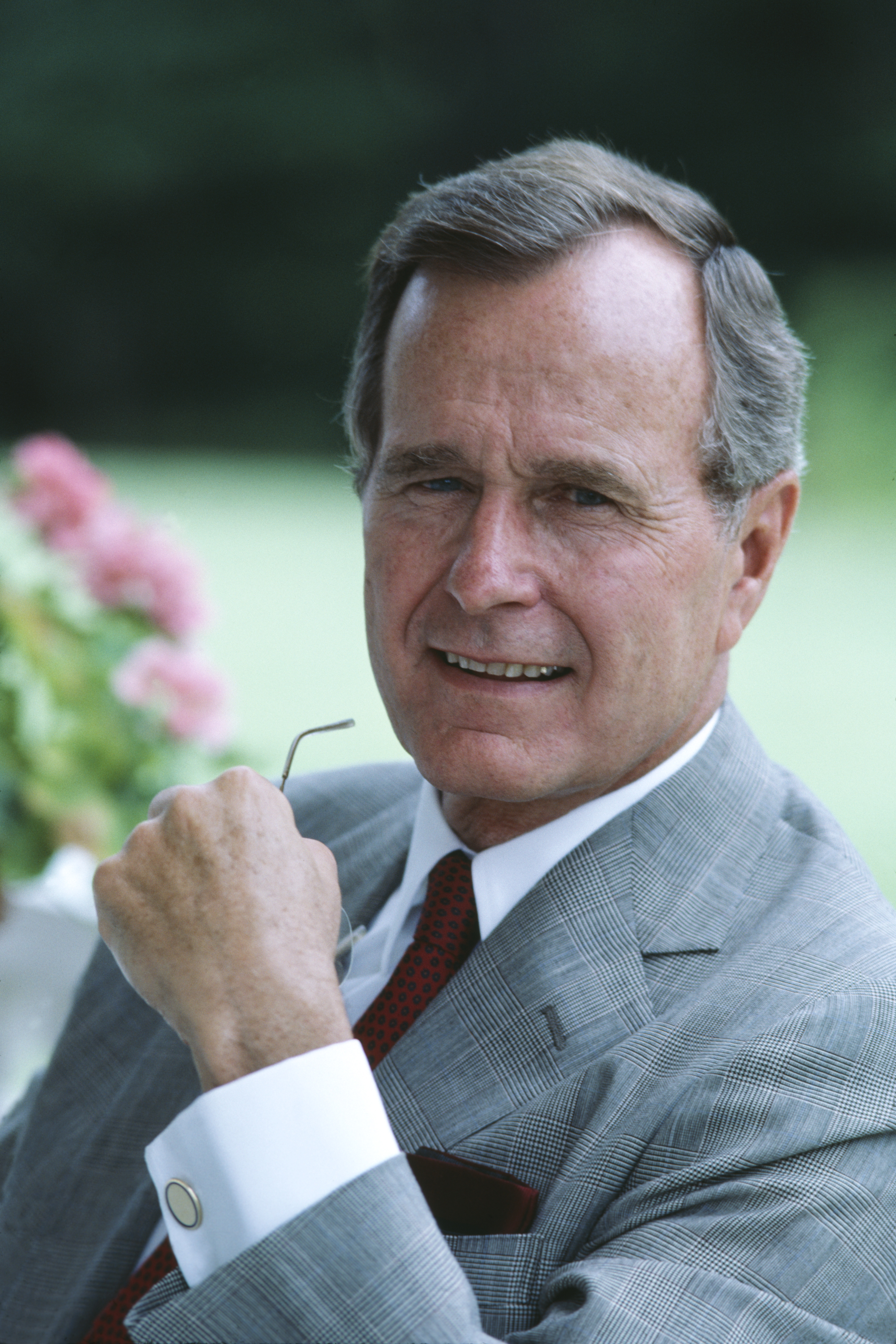

So we were lucky, but also well led. Just as any anonymous protestor or policeman could have destroyed the peace by picking up a brick or leveling a rifle, George H.W. Bush did more than anyone else to give peace the calm and quiet it needed to grow. Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev deserves more credit than anyone for the Cold War’s surprisingly sudden end, but as President of the United States, and thus as the world’s most influential leader, Bush did more to keep those crowds quiet and their troglodyte governments passive than any other statesman.

George H.W. Bush did more than anyone else to give peace the calm and quiet it needed to grow.

Note I did not say Bush was the world’s most powerful leader. He was that to be sure, but the immense power at his disposal as head of the world’s largest military power and economy was not the key to his success. He was instead influential for two reasons embedded within his sense of the power of his office: he was trusted, and he was composed.

The two went hand-in-hand. Known on the international stage for more than a generation by the time he won the White House, Bush brought to the presidency a resume and rolodex unmatched since Dwight Eisenhower, having served in Congress and then without complaint domestically and overseas under three successive Republican presidents. People knew what to expect when he walked in the room, a familiarity that when interpreted as a dearth of energy and originality, nearly cost him the 1988 election and then ultimately did ensure his defeat four years later. “We know what works,” he announced at his 1989 inaugural. “Freedom works. We know what’s right: Freedom is right. We know how to secure a more just and prosperous life for man on Earth: through free markets, free speech, free elections, and the exercise of free will unhampered by the state.”

The confidence embedded in that statement reeks of hubris, or at least thirty years later during a period of autocratic rise and seemingly endless conflict, as wildly overoptimistic. But global events appeared to confirm his belief as 1989 unfolded. The crowds chanting in Tiananmen “share our values,” his Secretary of State declared. Those who demanded freedom in Eastern Europe, “want our freedom,” and “what America has to offer.” The Soviet Union itself embraced democratic reforms, and for the first time in its short and bloody history, the first strains of a free market.

Nothing Bush said in response to these tectonic changes shocked or surprised, which was his goal: “I don’t aim to lead a crusade,” he’d stated when declaring his presidential bid in late 1987. He and those around him overestimated the universal appeal of American ideals, but one cannot overstate how fully they perceived the world going their way, democracy’s way, as the Soviet Union faltered.

So Bush was trusted because he was known, no fire-brand, and had not progressed up the political food-chain by proving false to his word, but the second part to his success in 1989 was his ability to urge calm on governments and crowds alike. Shocked as everyone else by the Wall’s unexpected fall, Bush’s political allies and underlings urged him to celebrate, to in effect spike the ball on the multi-generational Cold War effort, to declare ‘we won.’ He refused. It would have been good for his poll numbers, but “I’m not going to dance on the wall,” Bush told his aides, no matter how his apparent indifference in the midst of democracy’s apparent victory hurt his popular image. He was there to lead, not to be loved. “I’m not going to poke a finger in Gorbachev’s eye,” making the reforms the Soviet leader had initiated even harder to enact by riling up his domestic rivals, Bush further explained.

Bush’s political allies and underlings urged him to celebrate, to in effect spike the ball on the multi-generational Cold War effort, to declare ‘we won.’ He refused.

Given similar circumstances other leaders might have beat their chest, or in more recent days tweeted, taking personal credit for the free world’s multigenerational accomplishment, but Bush knew well that every defeated enemy was tomorrow’s potential ally. He’d only recently come from the funeral of the Japanese Emperor whose soldiers had shot him down over the Pacific forty-five years before.

And other leaders were calling, constantly the night the wall fell and in the weeks and months that followed, seeking guidance, or merely a strong anchor for a rapidly transforming international system. Britain’s Margaret Thatcher called; so too Germany’s Helmut Kohl and France’s Francois Mitterand. Even Gorbachev called, wondering like all the rest if Bush somehow knew what to do.

What he did, ultimately, was so very little and yet so very much. He did not shout, he did not gloat, he did not boast. Bush instead mostly listened during those tumultuous weeks and months of promise and anxiety in 1989, knowing that every time he listened more than he talked when a foreign leader called, and every time he kept his word, faith in him grew. As did a sense of calm responsibility he’d later put to good use when Saddam Hussein invaded Kuwait and when those conservative opponents of Gorbachev ultimately enacted the coup they’d long threatened.

Bush was hardly perfect as a president. He was cautious, unoriginal, and showed little flair for the pageantry of presidential politics. He overinflated his own credentials as an expert on China when Tiananmen rolled, and failed to remove the Iraqi despot who’d ultimately prove the bane of his own son’s presidency. He was not perfect. But during a moment when the world could very well have ended, his prudence was exactly what the world needed most.

Jeffrey A. Engel is the Director of the Center for Presidential History at Southern Methodist University and author of When the World Seemed New: George H.W. Bush and the End of the Cold War (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2017).