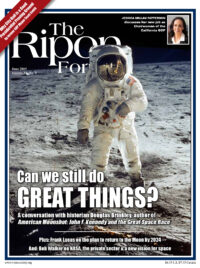

As the 50th anniversary of the first Moon landing approaches, politicians and bureaucrats in Washington, DC have allowed lunar lunacy to trump sober-minded space policy.

Calls by the Trump Administration and members of Congress for another manned lunar expedition have left the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) struggling to come up with a workable plan. And they have left taxpayers wondering how big the blank check will be for the next moon landing. The moon may be shrinking, but the price tag to return certainly won’t be.

The Administration’s original lift-off goal of 2028 has been accelerated to 2024, likely requiring the agency to spend billions of dollars more per year in the mad dash to get prepared. Amidst all of the hustle, bustle, and congressional criticism, few have questioned the underlying push to venture back into space. With little obvious benefit and gargantuan costs, policymakers should take their heads out of the clouds and leave manned exploration exclusively to the private sector.

Five decades ago, television viewers from around the world (except the USSR) heard the famous “one small step for man” uttered by the late, great Neil Armstrong. His giant leap for mankind cost American taxpayers around $20 billion in today’s money, while the entire cost of the six-series Apollo Program drained federal coffers by more than $100 billion.

But America had a space race to win, and despite considerable (and now forgotten) opposition at the time, successive Presidents and Congresses insisted on these missions going forward. Since the Nixon Administration, cost disease has taken root inside and surrounding the U.S. government, and a current U.S. mission would carry a considerably higher price tag than the Apollo Program. Even though NASA’s preliminary cost estimate has yet to be disclosed, some reports indicate that the agency will ask for an additional $40 billion over the next 5 years to facilitate an out-of-this-world request. But no matter what figure NASA reports to the public, taxpayers should take initial estimates with a capsule of salt.

Even though NASA’s preliminary cost estimate has yet to be disclosed, some reports indicate that the agency will ask for an additional $40 billion over the next 5 years to facilitate an out-of-this-world request.

The heavy-lift Space Launch System is tasked with bringing future astronauts to the Moon, but a four-month long audit conducted last year by the inspector general (IG) found that the project was nearly three years behind schedule and would cost double the original estimate. Meanwhile, the entire Europa Clipper mission – a promising search for life on Jupiter’s watery moon – was thrown into jeopardy after the cost of key mission equipment ballooned to $45 billion, three times the original estimate.

Because of this history of cost overruns, a 2004 Congressional Budget Office study pegged the cost of going back to the Moon north of $85 billion (in 2019 dollars). A 2009 committee convened by the Bush Administration found that costs would be a more manageable $60 billion (in 2019 dollars). At the very least, there exists around a 50 percent gap between what NASA is reportedly requesting from Congress and previous estimates. But maybe, lunar landing advocates insist, abstaining from manned missions is penny wise and pound foolish. Space exploration is often justified by pointing to the innovative research supposedly only possible by putting people into space.

But no matter what figure NASA reports to the public, taxpayers should take initial estimates with a capsule of salt.

For instance, microgravity makes it easier to enlarge proteins found in the human body, create intricate 3D models, and use these models to test out pharmaceuticals. But in 2016, researchers from the University of Bristol discovered that magnetic fields created here on Earth can have similar benefits to microgravity in aiding preliminary drug research.

If anything, the best “technological transfers” from NASA have come through unmanned, robo-centric missions, when researchers have to equip probes with state-of-the-art technology that won’t malfunction when humans aren’t around to fix it. Insulin pumps, for instance, can be reprogrammed without being removed from the body thanks to technology developed on the Mars Viking program in the seventies. But, miniature self-sufficient technology probably wouldn’t have been developed if the mission was manned, since humans would be able to collect and analyze samples using conventional tools. Sending humans in robots’ stead would also have been far more expensive.

Maybe, then, costly manned missions aren’t worth it after all. Mankind does seem to have a yearning to explore the cosmos and see other worlds, but robots can do just as good of a job (if not better) in reporting back to Mother Earth. Humanity can look back in gratitude at the Apollo astronauts and the feats they accomplish 50 years ago.

But we needn’t retread their footsteps. The robot age is here, with a potential to traipse new horizons without a gargantuan taxpayer bill.

Ross Marchand is the director of policy for the Taxpayers Protection Alliance.