by FRANK J. WILLIAMS

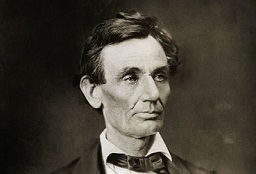

As Republicans prepare to select their nominee for President in 2008, it is a good time to reflect on the one decision that probably did more to shape the GOP than any other decision in the Party’s history – the decision by Abraham Lincoln to become a Republican.

It was not a decision that Lincoln took lightly. He was a staunch member of the Whig Party up until that point. Yet events in the country caused him to change course. Indeed, the birth of the Republican Party and Lincoln’s transformation from a local Midwestern politician to the greatest American President are intimately connected to the extraordinary tumult of mid-19th century America.

Any effort to consider why Lincoln became a Republican and his role in the formation of the Republican Party must begin with two basic points. First, a single issue united early Republicans – strenuous objection to the extension of slavery into the territories. Second, Lincoln’s passion was always for the principles of liberty in the Declaration of Independence, especially the principle that “all men are created equal.” Lincoln abhorred slavery, a position that led him to the Republican Party. Once a Republican, his broader philosophy made its mark on the party.

Lincoln was attracted to the party by his unwavering faith in the ideas espoused in the Declaration of Independence, even when faced with civil war.

Lincoln was a moderate in a radical party. His Whig roots and his faith in America’s founding principles made him an eloquent spokesman for the Republicans. Lincoln was attracted to the party by his unwavering faith in the ideas espoused in the Declaration of Independence, even when faced with civil war. He was no partisan zealot. He simply recognized that “the man who is of neither party, is not — cannot be, of any consequence.” Above all, Lincoln’s loyalty was to the Union and its founding ideals.

The story of the first Republican presidency begins with the divisive Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854, which abrogated the Missouri Compromise and ignited fears that Kansas or Nebraska might join the Union as slave states. An “anti-Nebraska” movement, soon to become the new Republican Party, took shape across the North. Lincoln was not initially inclined to align with the Party, even though he was invited to be member of its central committee in 1854. He declined the invitation, claiming he was still a Whig.

As it was, Whigs were becoming less relevant because they refused to face the growing crisis over slavery. Finally, in 1856, Lincoln attended Illinois’s anti-Nebraska conference and announced his desire to run for the United States Senate. He helped organize the first convention of the Illinois Republican Party, closing the convention with a speech “universally acclaimed as the best speech of his life.” Later, his name was offered as a vice-presidential candidate at the 1856 Republican National Convention. He did not receive the nomination, however, and returned to Illinois to continued prominence in the state party.

In 1857, the Supreme Court handed down the infamous Dred Scott decision in which Chief Justice Taney declared that blacks “had no rights which the white man was bound to respect.” The Dred Scott decision asserted that the Declaration of Independence did not apply to blacks. This decision was offensive to Lincoln and acted as a catalyst for him to reenter the national debate.

Lincoln’s powerful influence on his young party helped transform Republicanism from a single issue party to one devoted to broader ideals of liberty and optimism.

In 1858, the Illinois Republican Party nominated him for the United States Senate. During this campaign, Lincoln participated in the now-legendary series of debates with his political rival and the incumbent Democratic Senator, Stephen A. Douglas. In these debates and throughout the campaign, he perfected his moral rhetoric on the question of slavery, defining it as an eternal struggle between two opposing rights. “The one is the common right of humanity,” he declared, “the other the divine right of kings.”

Despite his soaring rhetoric, Lincoln was defeated by Douglas in the election. But his defeat set the stage for the presidential election of 1860. Lincoln emerged as the only Republican candidate who could unify the fractured elements of his young party. His election to the White House was secured against a divided opposition in the South, making Civil War all but inevitable.

Lincoln’s rise to the Presidency, his achievements once in office, and his eventual success in keeping the country together transcend party politics. His memory belongs to the history of the nation, and in some sense the history of democracy itself, not a political party. It is only natural that Republicans today would wonder about the lasting impact on their party of such a colossal figure. The answer begins with Lincoln’s original decision to leave the Whigs and become a Republican.

Lincoln was hesitant to leave the Whig party, so it only makes sense to consider the influence of his long held Whiggish principles. Lincoln, after all, attracted many former Whigs to the party. Who were the Whigs? Above all, they were economic optimists who believed wholeheartedly in the power of the individual to better himself, so long as society was properly ordered.

In Lincoln’s words, “[E]very man can make himself.” His strongly held notions of liberty combined with his “self-made man” ideal led naturally and forcefully to the right of free labor. This provided Lincoln with a natural transition from Whig to Republican. It also provided the GOP with a philosophical underpinning that remains critical to its political identity.

Lincoln’s powerful influence on his young party helped transform Republicanism from a single issue party to one devoted to broader ideals of liberty and optimism. His influence brought success to the anti-slavery cause and transformed it into an enduring political party still relevant today.

Times have certainly changed since Lincoln’s day, and now everyone takes Lincoln as their own: liberals, conservatives, labor, and business; but he remains the quintessential Republican. For his part, Lincoln became a Republican because he believed people are at their best when they are free.

One hundred and sixty one years later, that sentiment has become a bedrock principle of our Nation and has taken hold around the world, as well. RF

___________________________________

Frank J. Williams is a life-long student of the life and times of Abraham Lincoln. He is also the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of Rhode Island and the founding chair of The Lincoln Forum, an international organization devoted to the study of Abraham Lincoln and the Civil War. A member of the U.S. Lincoln Bicentennial Commission, he is the author of the 2002 book, “Judging Lincoln.” He would like to thank Terrence Haas, Esq. for his research assistance on this essay. This article is purely historical and does not represent the political views of the author.