The United States and its global allies are facing unprecedented challenges to democratic governance in 2020. Few are spared from traditional issues like voter apathy and legislative gridlock or more recent problems such as the heavy flow of migrants or foreign election interference. But the fact that so many democracies in so many places are dealing with the same concerns at the same time means there’s an unprecedented opportunity to work together on shared solutions.

In the U.S., the idea of democratic nations working together has long had bipartisan appeal. The late Senator John McCain called for a “League of Democracies” during his 2008 run for president. This year, a plank in Joe Biden’s presidential campaign platform raises the idea of a summit of democracies. Other democratic nations are keen for something similar. When President Trump mentioned his interest in expanding the G-7 meeting to include Russia, the proposal was greeted unenthusiastically. U.K. Prime Minister Boris Johnson proposed instead a “D-10” gathering of democracies, which would add Australia, India, and South Korea to the existing G-7 (but exclude Moscow).

The objective of each of these proposals was for democratic states to take coordinated action when there was a threat to the rules-based international order. McCain’s “league” was meant to act when China or Russia vetoed U.N. Security Council action on human rights or Western security issues. Biden’s democracy summit is projected as an opportunity to reset the U.S. as a global leader within the multilateral system. And Johnson’s D-10 idea was offered with a focus on discussing 5G mobile networks and strengthening vital supply chains.

To these challenges must now be added another matter of major global concern requiring democratic solidarity — the COVID-19 pandemic. Although the novel coronavirus is not confined by any border or particular political system, it undeniably burst onto the scene from a non-democratic nation, China, whose initial reaction was to devote considerable state resources towards silencing those who sounded the alarm.

A study of epidemics between 1960 and 2019 in the June 6 edition of The Economist found there to be a correlation between lower death rates and countries where the basic tenets of democracy are firmly in place.

In response to the virus, not every democracy has performed successfully, and not every authoritarian system has failed. The U.S., for example, has struggled, while Vietnam is tackling the crisis effectively. But resiliency and an ability to self-correct through constitutional procedures and access to freedom of information and opinion are hallmarks of democracy that are essential to overcoming a crisis. And while data on COVID-19 is still being collected, a study of epidemics between 1960 and 2019 in the June 6 edition of The Economist found there to be a correlation between lower death rates and countries where the basic tenets of democracy are firmly in place.

“Most data suggest that political freedom can be a tonic against disease,” the study found. “Though these outbreaks varied in contagiousness and lethality, a clear correlation emerged. Among countries with similar wealth, the lowest death rates tend to be in places where most people can vote in free and fair elections. Other definitions of democracy give similar results … People who praise China for its handling of covid-19 would do better to look at Taiwan, a neighbouring democracy. China wasted valuable time in December by intimidating doctors who warned of a lethal virus. Taiwan swiftly launched tracing measures in January — and has suffered only seven deaths.”

The inherent resilience of democracies and their ability to course correct is the focus of a recent statement on the COVID-19 pandemic issued by the Community of Democracies, an intergovernmental coalition of democratic states seeking to coordinate action on issues of the rule of law, democracy, and human rights. Called the Anniversary Bucharest Statement, the pronouncement was drafted and adopted by the United States and 28 other democracies on June 26. Among other things, it cautions governments that the cure for this crisis should not be worse than the crisis itself.

“In some cases,” the statement warns, “measures to address the pandemic are being misused to restrict civil liberties, centralize power, manipulate electoral processes, reverse gender equality gains, and expand exclusionary practices against marginalized groups and persons. Emergency measures may be necessary to protect public health, but they should be evidence-based, proportionate to the public health risk and short in duration, and regularly reconsidered as the situation evolves, with the aim of leaving democratic procedures and human rights in full force.”

Beyond this, the statement also addresses the impact the pandemic may have on core democratic activities, including: elections, the ability for citizens to access information and engage in free expression; equal access to education; and, freedom of assembly and association.

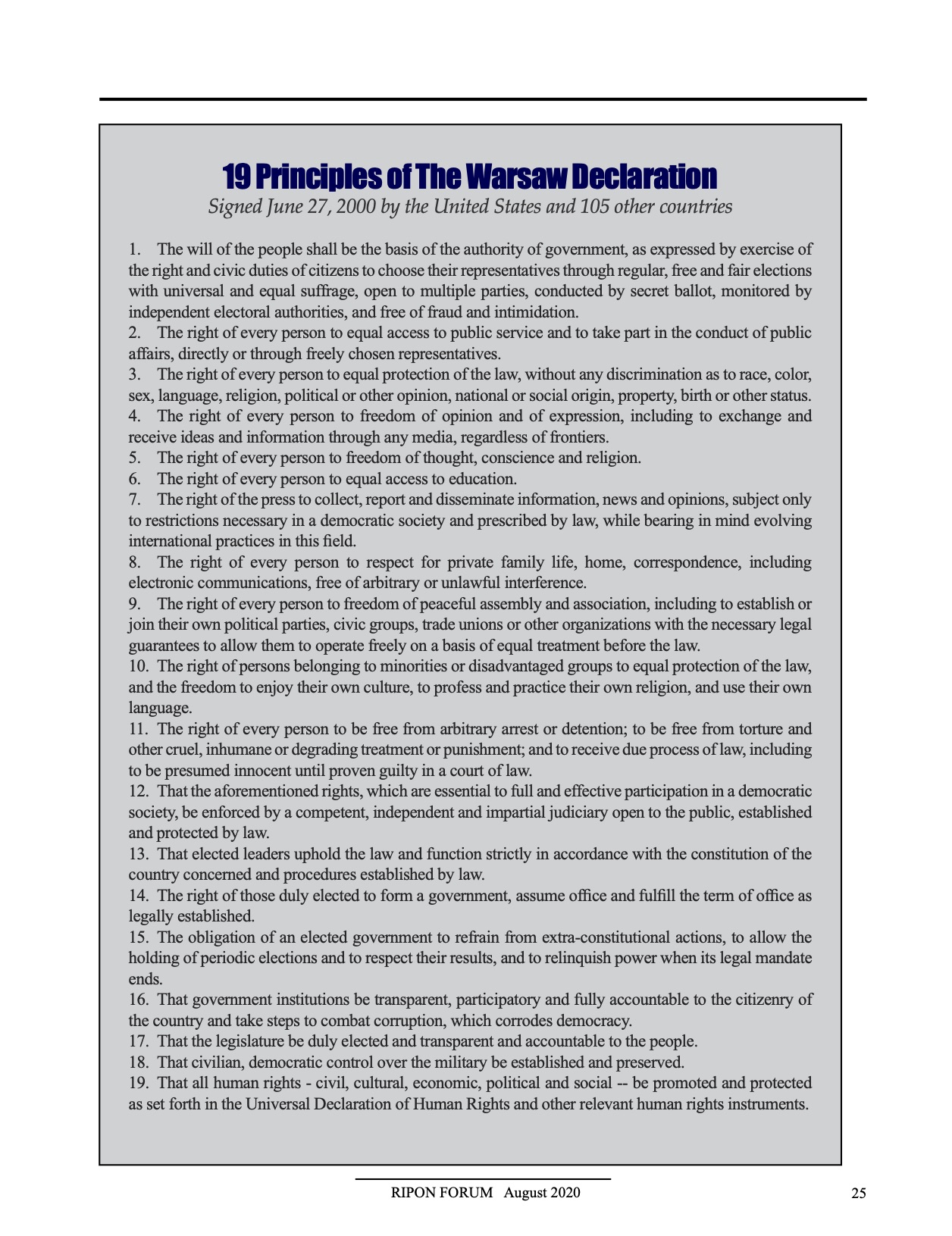

These activities and other essential freedoms are key elements of the Community of Democracies’ Warsaw Declaration, a set of 19 principles adopted by 106 democratic states in June 2000 — the largest gathering of democracies until that time. Together, the countries agreed that, while diversity existed among their political systems, there are universal standards that must be present for a nation to call itself a democracy. In addition to the United States, the countries signing the Declaration and endorsing these principles included Germany, Thailand, New Zealand, Russia, Nicaragua, Venezuela, and Egypt.

Clearly, a lot has changed over the past two decades. Russia is now ruled by Putin, not Yeltsin, and Venezuela has become a failed state. But the principles that form the basis of the Declaration have stood the test of time. And as the world confronts the challenges posed by COVID-19, it is critical that the democratic nations of the world keep our shared principles in mind moving forward. This is especially true at a time when the international order and many of the multi-national organizations that have been established to maintain this order are being questioned and coming under assault.

As the world confronts the challenges posed by COVID-19, it is critical that the democratic nations of the world keep our shared principles in mind moving forward.

America’s recent withdrawal from the World Health Organization is not without precedent. President Jimmy Carter withdrew the United States from the International Labor Organization in 1977, while President Ronald Reagan pulled the U.S out of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization in 1984. While these decisions were reversed by later Presidents, the fact remains that America has withheld support from international organizations before. What is without precedent is for democracies to go it alone in the face of such an unprecedented crisis as COVID-19, and effectively cede influence of an organization as influential as the WHO.

A far more effective course would be for the U.S. to bring democracies together under our shared set of principles and work to shape the agenda and direction of the WHO and other multi-lateral forums in the months and years ahead. For at the end of the day, these principles are not only the links that unite us, but ones that will keep our nations — and the world — healthy, safe, and free.

Thomas E. Garrett serves as Secretary General of the Community of Democracies.