At this time of year politicians are often portrayed as Santa Claus, joyfully doling out spending goodies and tax breaks to grateful constituents. This comparison does a gross injustice to Santa. When he delivers presents he doesn’t slip a bill for several trillion dollars into our kids’ stockings. If politicians want to play Santa Claus, they should start by giving today’s children a present they really need—a sustainable fiscal future.

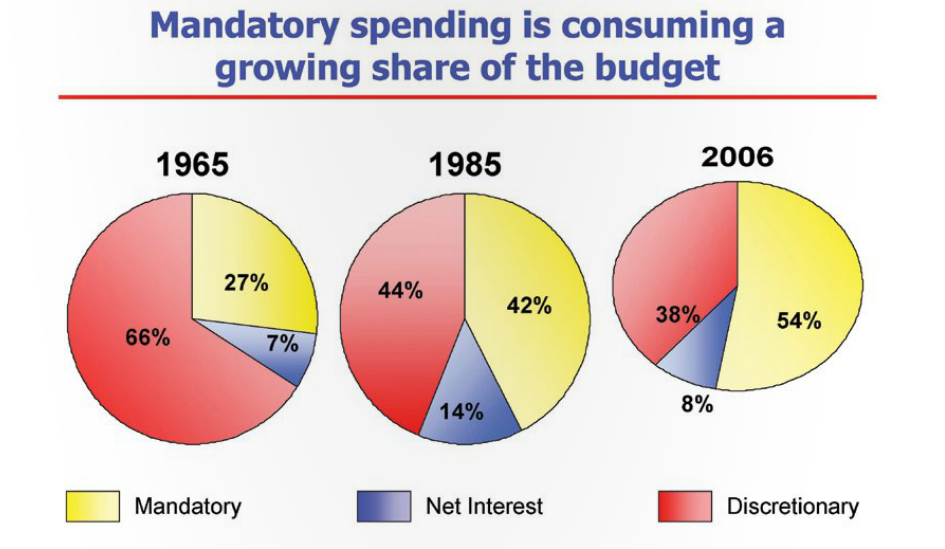

Consider the gift package that awaits future generations. A major demographic shift to a permanently older society will put enormous pressure on the federal budget. Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid are projected to grow by 27 percent as a share of the economy (GDP) in the next 10 years. As a result, these programs, which consumed 40 percent of the budget in 2006, will consume 51 percent by 2016—and that is just the tip of the demographic iceberg.

Demographic change, however, is only part of the problem. Health care prices, on average, have outpaced economic growth by 2.6 percentage points annually since 1960. If this continues, by 2050 Medicare and Medicaid will absorb as much of our nation’s economy as the entire federal budget does today. Most of that increase would come from the rising cost of health care rather than demographics.

Higher savings today would contribute to a larger economy tomorrow, and that would make the looming fiscal burden more affordable. Unfortunately, here, too, we are not acting with regard for the future. Americans’ personal savings rate as a percentage of disposable income has steadily declined from over 7 percent in the early 1990s to negative 0.4 percent in 2005. Net national saving, public and private combined, has plummeted from 8.5 percent of gross national income 25 years ago to essentially zero today.

In the absence of domestic savings, foreign sources have taken up the slack. The portion of the government’s privately held debt owned by foreign investors has risen dramatically since 2001 – from 37 percent to 52 percent. Reliance on foreign borrowing increases the budget’s exposure to international capital markets and decisions made by foreign interests. Moreover, interest payments on the national debt go to bond holders from abroad, and this acts as a growing mortgage on future national income.

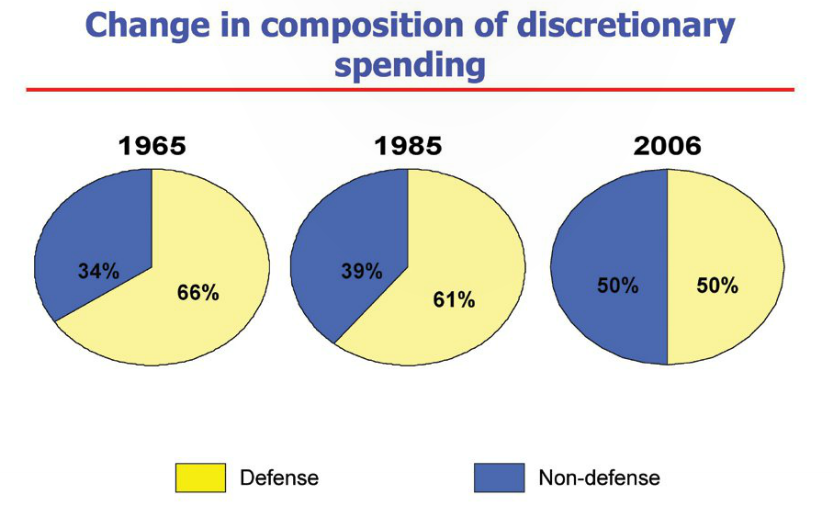

Beyond fiscal imbalance, today’s budget policies threaten to place ever-tighter constraints on the ability of future generations to determine their own priorities or to meet challenges that cannot be foreseen. As the share of federal resources pledged to retirement and health care benefits grows, it will leave shrinking amounts for all other purposes.

The bottom line is stark. We are expecting our children to support growing promises for retirement and health care benefits while doing very little to invest in the future economy that will have to produce those benefits. No nation can prosper without investing, nor can it invest for long without saving, nor can it save for long without a responsible fiscal policy.

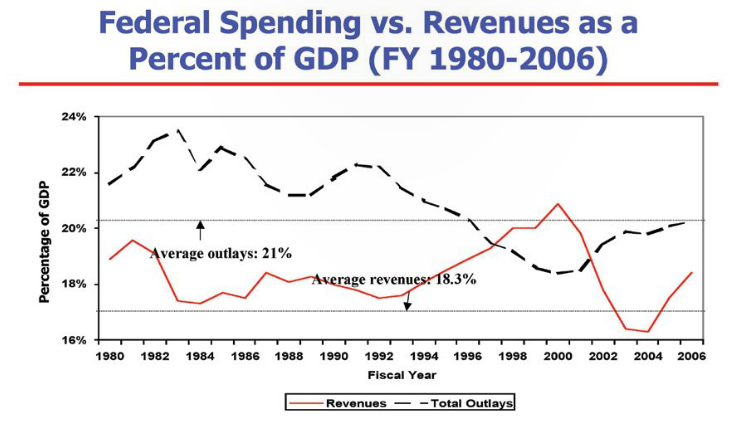

Responsible, however, is not a word that describes current fiscal policy. In the past few years, lawmakers have simultaneously enacted large tax cuts and piled huge new spending commitments on top of an already unsustainable burden. Total spending has gone up from $1.79 trillion, or 18.4 percent of GDP in 2000 to $2.7 trillion, or 20.3 percent of GDP in 2006. Incredibly, the unfunded obligations of the new Medicare prescription drug benefit are roughly 50 percent more than those of the entire Social Security program. There is no plan to pay for all this budgetary largesse other than running up the national debt, which now stands at $8.6 trillion.

If politicians want to play Santa Clause, they should start by giving today’s children a present they really need – a sustainable fiscal future.

A more comprehensive way to measure the mounting fiscal burden is to total up the government’s explicit liabilities, such as the national debt, and its implicit obligations, such as future Social Security and Medicare benefits. According to the Government Accountability Office (GAO), all such “fiscal exposures” have a present value of $46 trillion—almost as much as today’s total national wealth and equivalent to $375,000 per full-time worker in the United States.

There is at least one positive thing to report on the budget front: at $248 billion (1.9 percent of GDP), the deficit in fiscal year 2006 was lower than the $319 billion deficit in 2005 (2.6 percent of GDP). It was the second year in a row that the deficit declined. This does not mean, however, that we are on a smooth and easy road back to balanced budgets. Both the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) and the President’s Office of Management and Budget (OMB) project an increase in the deficit next year.

Total spending has gone up from $1.79 trillion, or 18.4 percent of GDP in 200 to $2.7 trillion, or 20.3 percent of GDP in 2006.

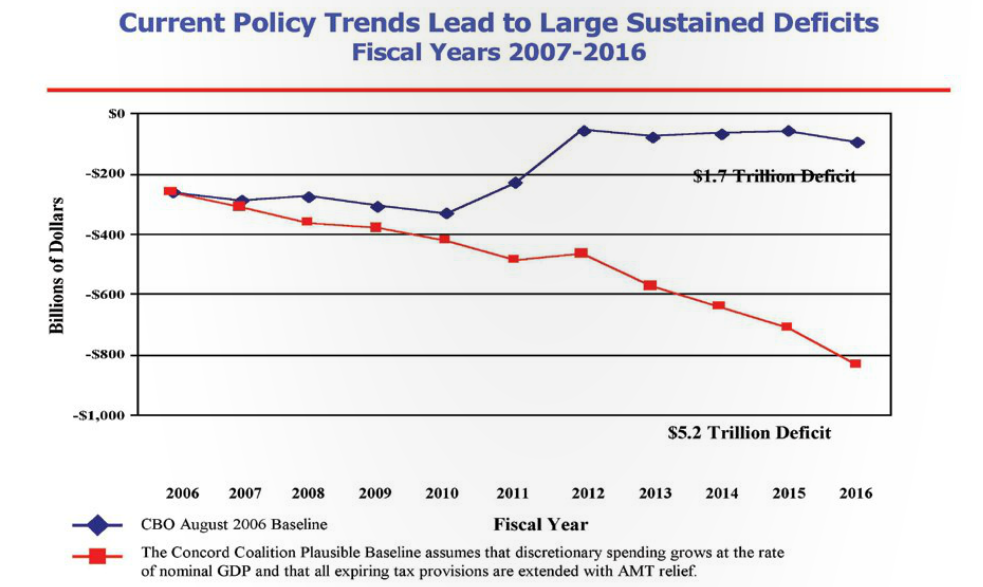

Budget projections are uncertain, but under plausible assumptions about current trends, deficits would total $5.2 trillion through 2016. This assumes that funding in Iraq is phased down, that all expiring tax cuts are extended, that appropriations grow at the same rate as the economy, and that the Alternative Minimum Tax (AMT) is adjusted for inflation. It also assumes a healthy economy.

Under that scenario, deficits would steadily rise to 4 percent of GDP by 2016. Persistent deficits of that size, while not unprecedented, are nevertheless harmful and would come at a very bad time. They would drain national savings, raise the debt to GDP ratio and increase interest costs at the very time when we should be doing the opposite in preparation for the looming fiscal challenges as the baby boomers retire and entitlement spending balloons.

As government debt increases, interest costs grow as well. These costs add to government spending and are paid for with tax dollars. Interest costs totaled $227 billion in fiscal year 2006. It was the fastest growing major spending category in the federal budget, increasing by 24 percent. We spent more on interest in 2006 than we did on either the federal government’s share of Medicaid ($181 billion) or appropriations for military operations in Iraq and Afghanistan ($120 billion). All of this is occurring as we enter our fifth year of economic recovery and with two years of very strong revenue growth.

Problematic as the 10-year outlook is, longer-term projections are even worse. Today, federal government spending absorbs 20.3 percent of the economy. At the high end of what the CBO sees as a possible range, federal spending, excluding interest, could rise to 34 percent of GDP in 2050. Federal tax receipts have hovered in the range of 18 percent of GDP over the past half century. If retirement and health care entitlements are allowed to grow on autopilot, pushing total federal spending above 30 percent of GDP, and Americans’ reluctance to pay taxes above 20 percent of GDP holds true, the resulting deficits will rapidly escalate to dangerous levels. A deficit equaling 10 percent of GDP in today’s terms is the equivalent of $1.3 trillion. That amount is more than five times the size of the 2006 deficit.

Borrowing our way through the problem is not a viable option because the rising cost of Social Security, Medicare and Medicaid gets bigger with time. Incurring ever-rising levels of debt would result in staggering interest costs and ultimately a level of debt that would crush the economy. Nor can we grow our way out of the problem. The GAO has estimated that it would require real (inflation-adjusted) average annual economic growth in the double-digit range every year for the next 75 years to close the gap. Given that real economic growth has averaged about 3 percent annually over the last thirty years, any idea of growing our way out of the problem is more of a fantasy than a plan.

What about cutting waste, fraud and abuse? These things exist throughout the federal budget and every effort should be made to eliminate them. Unfortunately, there is no line-item in the budget labeled “waste, fraud and abuse.” What may seem like waste to some can seem like vital government services to those who directly benefit from them. Stories about “bridges to nowhere” and other such earmarked spending justifiably diminishes public confidence in Congress’ willingness to exercise fiscal discipline, but if all such earmarks were eliminated, and the money not simply reprogrammed to be spent elsewhere, it would only save about one percent of all federal spending.

Another seemingly painless option is to cut taxes and “starve the beast,” but experience has demonstrated that this is a failed strategy. Ultimately, the tax burden is determined by the government’s spending commitments and not the other way around. Moreover, Dr. William Niskanen, a former Chairman of the Council of Economic Advisers under President Reagan, has found that spending tends to increase as a percentage of GDP when revenues decline. The reason is simple – cutting taxes and relying on borrowing to continue the current level of spending shields taxpayers from the true cost of government. As a result government services seem “cheaper” for taxpayers, which creates a greater demand for even more spending.

The real choices require scaling back future health care and retirement benefit promises, raising revenues to pay for them or—most likely—some combination of both. Americans may have very different views about whether it would be better if the federal government were both taxing and spending at 18 percent of GDP or both taxing and spending at 30 percent of GDP. Yet no one would advocate that the government tax at 18 percent of GDP and spend at 30 percent. This would certainly shatter the economy. And this is precisely the future we are now embarked upon.

Indeed, the rapid increase in federal revenues over the past two years has prompted some to suggest that revenue increases should not be on the table because tax cuts pay for themselves through greater economic growth. It’s a politically convenient theory, but the evidence does not support it. Indeed, the revenue “record” of $2.41 trillion in 2006 is not remarkable because revenues almost always set a record in nominal dollars every year as revenues naturally increase with inflation, economic growth and other factors. What is remarkable is that the revenue record set in 2000 ($2 trillion) was not broken until 2005. Between 2001 and 2003 revenues actually declined for three years in a row. Moreover, revenues in 2006 represented a much lower percentage of the economy than in 2000 before the tax cuts were enacted — 18.4 percent of GDP as opposed to 20.9 percent. Measured in inflation-adjusted terms, revenues in 2006 were almost identical to 2000 revenues despite five years of economic growth. In fact, revenue from individual income taxes is still below 2000 levels, adjusted for inflation.

Economists from the left and right generally agree that tax cuts do not fully pay for themselves. A July 2006 analysis by the U.S. Treasury Department suggested that the economic feedback from extending the 2001 and 2003 tax cuts would offset less than ten percent of the revenue loss, and would only do so if the tax cuts were offset by spending cuts, something that has neither happened nor been proposed. The lesson is that debt is not a painless alternative to taxes. Whatever government spends, it must eventually pay for. Unless we reduce spending over the long-term we are not really lowering the tax burden over the long-term but merely shifting it from ourselves to our children.

Generational fairness requires a major course correction. The choices we make today will determine what kind of society our children and grandchildren inherit 20 and 30 years from now. Inaction increases the prospects of severe changes later. By contrast, modest reductions in projected entitlement costs, enacted promptly and phased-in over many years, could have a substantial impact in bringing future costs down to a more sustainable level, while giving people a chance to adjust their expectations of the extent to which their retirement years will be financed by future taxpayers. Similarly, eliminating or even reducing the budget deficit over the next few years would generate major savings in future interest costs.

The sooner we get started the better. Budget rules, such as realistic caps on appropriations and a “pay-as-you-go” rule that applies to both entitlement expansions and tax cuts, can help in this regard. However, rules are not a substitute for the political will needed to make tough choices. A realistic strategy will require that someone give up something—either in reduced promised benefits or higher taxes. Because this reality is politically problematic, serious action is not likely to occur unless it is the result of a bipartisan process with greater public awareness of the need for trade-offs. Everything must be on the table to ensure that the total mix of spending, taxes and debt does not reach levels that could damage the economy and reduce future standards of living.

Let’s hope that the new Congress, the current President and the crop of would-be presidents in the 2008 campaign decide to be more like the real Santa Claus by supporting policies that put our children’s future ahead of short-term political satisfaction.

Robert L. Bixby is Executive Director of the Concord Coalition, a nonpartisan, grassroots organization dedicated to fiscal responsibility.