It’s been said that Michigan Governor Rick Snyder is no ideologue. That may be true in the sense that he has largely avoided becoming a “lightning rod” reformer in the style of other GOP governors. But it’s not true in the sense that he brings no core beliefs to governance.

Governor Snyder has largely demonstrated that he believes that free enterprise is the key to Michigan’s prosperity. He has also doggedly viewed state government through the lens of the CPA that he once was — which is not a bad place to start for a governor inheriting a state in crisis like Michigan was when he took office in January 2011.

Snyder gave his marching orders early on, effectively saying that he wanted to balance the budget and lower taxes, even if some sacred cows had to be sacrificed along the way. In response to this mandate, policymakers went to work. They cleaned up the income tax, started getting rid of those hideously complex corporate tax loopholes and some of the most egregious business subsides, and saw to it that people got to keep more of their own money in the end. The governor also signed legislation that offended pensioners by raising their taxes to the level others paid, shocked big business by severely pruning corporate welfare and tax favors, and helped the economy by lowering taxes $700 million overall, thereby allowing the first state budget surplus in years.

Governor Snyder has … viewed state government through the lens of the CPA that he once was — which is not a bad place to start for a governor inheriting a state in crisis like Michigan was when he took office in January 2011.

These policies and others have coincided with an economic reversal in the state. As Mackinac Center for Public Policy analyst James Hohman wrote, “Michigan’s economy added 166,400 private-sector jobs since the beginning of Snyder’s term, a five percent gain. Michigan’s personal income increased 9.3 percent from 2010 to 2011, placing 19th among the states. That might not sound like much, but Michigan’s hasn’t beaten the national average since 2003 and before that one-year blip, since 1994.”

University of Michigan economist Don Grimes also found that Michigan ranked second behind North Dakota in private sector job gains in 2011. “How much of this can you credit Snyder with?” Grimes asked in a column he wrote for Michigan Capitol Confidential, which is published by my organization. “I don’t know,” he continued, “but I do know the state is now on the right track.”

Grimes also cautioned against attributing too much of the turnaround to the federal auto bailouts.

Measuring Results

Modern politics produces a strain of outsider politician whose reform mantra is, “We have to run government like a business.” Governor Snyder has an impressive and extensive business background, and he is sympathetic to that cry.

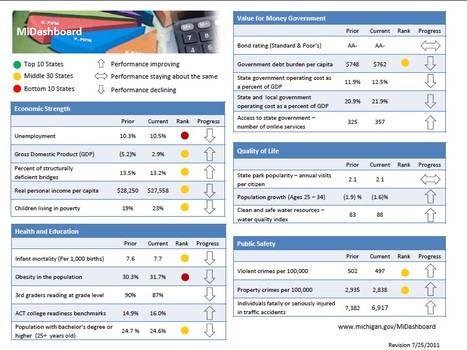

Citing former Indiana Governor Mitch Daniels as his role model, he has tried to make “customer service” a government reform rallying call. He created a series of public, government performance “dashboards” whose format would look at home in any corporate boardroom. Dashboards are common in corporate culture but comparatively rare in government.

Like the displays of key variables constantly before drivers’ eyes – speed, oil pressure, fuel level, etc. – Snyder’s web-based dashboards display measurements of the states’ economy, finances, education system, public safety, health and wellness, infrastructure, environment, and quality of life in a way that allows easy year-by-year comparisons. Users can drill down to reveal a total of 165 metrics (by my count). Numbers trending the “right” way get a green thumbs up. The others get a red thumbs down. It doesn’t look like a government website.

Two things are notable about the dashboards. The first is that they exist at all. It’s bold and admirable for a governor to publicly declare, shortly after election, the precise measurements by which he invites voters to judge his performance, and then to make it easy for voters to monitor those measurements. But it is the kind of thing a CPA-cum-businessman might suggest.

Snyder’s web-based dashboards display measurements of the states’ economy, finances, education system, public safety, health and wellness, infrastructure, environment, and quality of life in a way that allows easy year-by-year comparisons.

The second is the broad scope of the measurements Snyder chose. As governor, he has some direct control over a few of those measurements such as state deficits, surpluses and reserves, but only slight influence at best over many more such as obesity and excessive alcohol consumption. Other measurements are only questionable contributors to the state’s overall well-being, such as annual state park visits per capita.

Some measurements make only a bit more sense than would a measurement of the number of sunny days. These create an incentive for the governor to try to control things which may be beyond the scope of government’s legitimate powers. A business world dictum is that one cannot control what one does not measure. Measurement is therefore often the first step for changing something that actually can be controlled but needs to be better, such as reducing workplace injuries. But does Governor Snyder really want a government powerful enough to control obesity and excessive alcohol consumption?

A dashboard can’t measure everything that’s important; in particular, a dashboard provides no feedback on the destination of the driver. Perhaps the trip is headed in entirely the wrong direction, such as the potential Medicaid expansion on which the Obamacare implementation hinges. Further, a dashboard is inherently a reflection of what the car’s designer thinks is important, not necessarily what everyone thinks is most important. Perhaps instead of state park visits, the dashboard could measure the average time to issue an industrial permit, or any permit for that matter. Or obesity measures could be replaced with the average amount of time it takes to adjudicate state court cases. These are much more directly related to the governor’s authority, and vitally important to the health of the state.

A dashboard can’t measure everything that’s important; in particular, a dashboard provides no feedback on the destination of the driver.

While these and other measurements do not appear often in the daily headlines, that may change as the election season grows nearer and his opponents seize upon some of the weaker metrics of the past two years. Still, his critics will not be able to find fault with this basic fact – namely, that Governor Snyder’s Michigan performance dashboards represent an arresting honesty, transparency and sincerity in the state’s chief executive.

Perhaps most importantly, they add confidence in the character of the governor — which is critical not only at a time when trust in government is at or near an all-time low, but when people are demanding value for their tax dollars they entrust to the state.

Joseph G. Lehman is the President of the Mackinac Center for Public Policy, a nonpartisan, nonprofit research and educational institute.