One of the ongoing debates in Washington these days is whether tax rates should be lowered to create jobs and stimulate sound economic investment. Of course, this is not a new concept.

Indeed, the 1986 Tax Reform Act was based on this concept. Before the Act was passed, the top personal tax rate stood at 50 percent, while the top corporate rate was 46 percent. After passage, the top personal rate had been reduced to 28 percent, while the top corporate rate had been reduced to 34 percent.

In making these reductions, the Act neither lost nor raised money. Instead, the measure was revenue neutral – an accomplishment that was not only achieved by getting rid of deductions, but one that could be repeated today.

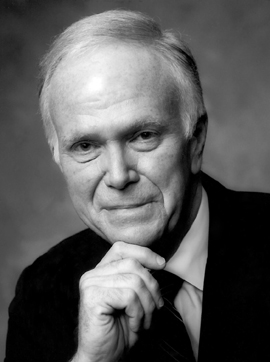

The Original Gang of Seven

In setting the stage for the ‘86 debate, one must first recall the politics of the time.

In 1985, we had a Republican-controlled Senate, but the House was overwhelmingly Democrat. The GOP had not held a majority in the House since 1954.

In fact, they had been out of power for so long that Democrats — assuming Republicans would never retain control of the chamber – excluded Republicans from participating in the writing of the tax bill.

The tax reform bill was referred to the Rules Committee, with Ways and Means Committee Chairman Dan Rostenkowski insisting that it not be open to amendments. But when the ensuing rule went to the House floor, it was defeated, thus opening up the bill to amendments, and causing Rostenkowski to pull it.

At this point, President Ronald Reagan asked the House Republicans to vote for the rule and in essence the bill itself, but adding if it came to him in this fashion he would veto it. The legislation was subsequently approved by voice vote, and was sent to the Senate.

As Chairman of the Finance Committee, my job was to get the rates as low as possible and make the bill revenue neutral. At that time in the Senate, we had a reasonable history of bipartisan cooperation on major issues. On taxes, there seemed to exist a natural marriage, as well. Republicans wanted lower rates; Democrats wanted to close what they thought were unjustified “loopholes.”

As Chairman of the Finance Committee, my job was to get the rates as low as possible and make the bill revenue neutral.

On the Finance Committee, we had particularly good bipartisan working relationships, and I chose Democrat and Republican members on the committee whom I knew I needed to accomplish the goal. Moderate Republican Senators John Chafee (R-RI) and John Danforth (R-MO) were two of my closest friends, and conservative Republican Senator Malcolm Wallop (R-WY) was a close ally.

Senator Daniel Moynihan (D-NY), one of the intellectual leaders of the Senate Democrats, was my closest friend in the Democrat party. And I knew Bill Bradley could be counted on as a strong supporter of eliminating deductions. A good working relationship with Democrat committee member George Mitchell would bring along other Democrats.

We had the small working team of seven, but we knew we had to move very quickly. Any group that was going to lose deductions would fight us. If this reform was to be accomplished, it would have to be done secretly — we had to take the opposition completely by surprise before they could organize against it.

Every morning for just six days, that working group would meet in my office at 8:30 a.m. and agree on what we wanted to accomplish at the full, public finance committee meeting later. Those seven committed votes — and the fact that those seven members were the natural leaders of the committee — were key to the success of passage of the bill out of the Finance Committee.

In six short days — with secret negotiations among seven Senate leaders from both sides of the aisle who could work together, and with give and take for the greater good — we had a piece of legislation that became the most significant change in the U.S. tax code since its creation some 75 years earlier.

I had to make just one major concession to a group of oil state senators who wanted a form of passive losses which we had eliminated in the draft bill. It was a strategic decision to give the oil state senators their passive loss provision. By compromising with them, I got their full support for the bill and it passed out of the Finance Committee with a 20-0 vote instead of a 12-8 vote. That 20-0 vote was the basis upon which the bill went to the Senate floor and passed by an overwhelming vote of 97-3.

In six short days — with secret negotiations among seven Senate leaders from both sides of the aisle who could work together, and with give and take for the greater good — we had a piece of legislation that became the most significant change in the U.S. tax code since its creation some 75 years earlier.

Lessons Learned and Today’s Debate

Can meaningful tax reform be accomplished today? I believe with leadership and focus, it most certainly can. Here’s how:

Very quickly, and on their own, the House Republicans need to focus on passing a revenue neutral tax bill. They should not try to solve the deficit problem in the bill. They should not try to solve the Medicare problem in that tax bill.

A bill that is revenue neutral, lowers the individual and corporate rates to the mid-twenties, and keeps it current progressivity — where the higher income people pay a higher percentage of taxes — should get support from a broad spectrum of economists. It will also garner a good liberal and conservative cross section of editorial comment.

The Senate will not want to stop a bill that gets such broad support. Timing and leadership is essential to passage of any meaningful tax reform. The time is right. Meaningful tax reform will go a long way to curing the ills of our current economy, and money will be invested based on good business decisions, instead of being based on distorting incentives in the tax code. Meaningful tax reform will remove the whole class warfare fight because the richer will pay a progressively higher rate of taxes.

The goal of lowering rates is worthwhile. Our economy will greatly benefit, and the argument about the rich not paying their fair share will have the rug pulled out from beneath it. The U.S. House can and should act quickly.

It will take leadership and focus to pass a revenue neutral tax bill, but it can be done. We proved that with the 1986 Tax Reform Act.

Bob Packwood served in the United States Senate from the State of Oregon from 1969 to 1995.