To the naked eye, the American jobs machine is broken. Between 1950 and 2000 the U.S. economy created an average of 145,000 jobs (“non-farm payroll employment”) every month. Since then the average is a startling decline of 4,000 jobs monthly.

But digging a bit deeper suggests that the stall consists of one part predictable demographic shifts, and one part policy errors. The latter has hampered the two most recent recoveries – each of which has earned the well-deserved moniker: “jobless recovery.”

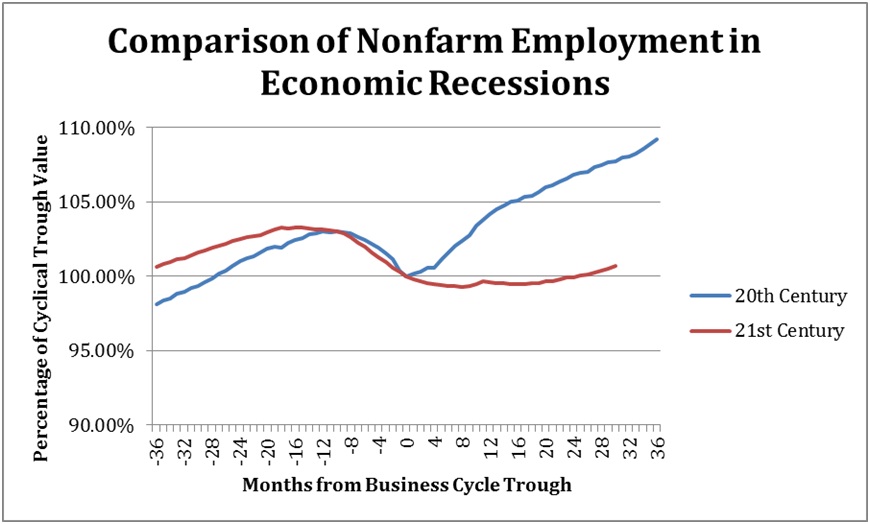

Consider the chart below:

As shown in the blue line, during the average 20th century recovery, employment was 5 percent above the low point after 16 months, and nearly 10 percent above after 3 years. In contrast, the past two recoveries have been abysmally anemic, with employment barely above the trough after over two full years. (Interestingly, the profiles are remarkably similar for the year of decline before the trough.) So, both from the perspective of the longer trends and the recovery something seems amiss.

Stepping back, in part the slowdown should have been anticipated. During the final five decades of the 20th century the labor force grew at the healthy rate of 133,000 each month, a reflection of the baby boom, immigration, and generally rapid population growth. In the 21st century the monthly increase has fallen to a bit above one-half of that – only 76,000. As the U.S. ages and population growth slows, there is slower top-line growth in the demand for goods and services, which requires fewer new jobs to supply the products and meshes nicely with the slower growth in the supply of labor.

During the final five decades of the 20th century the labor force grew at the healthy rate of 133,000 each month… In the 21st century the monthly increase has fallen to a bit above one-half of that – only 76,000.

So, one part of slower job growth was baked in the cake, as it is a tenet of modern analysis that advanced economies will ultimately always return to full employment (with emphasis on ultimately) and long-run job growth will be driven by the supply of labor.

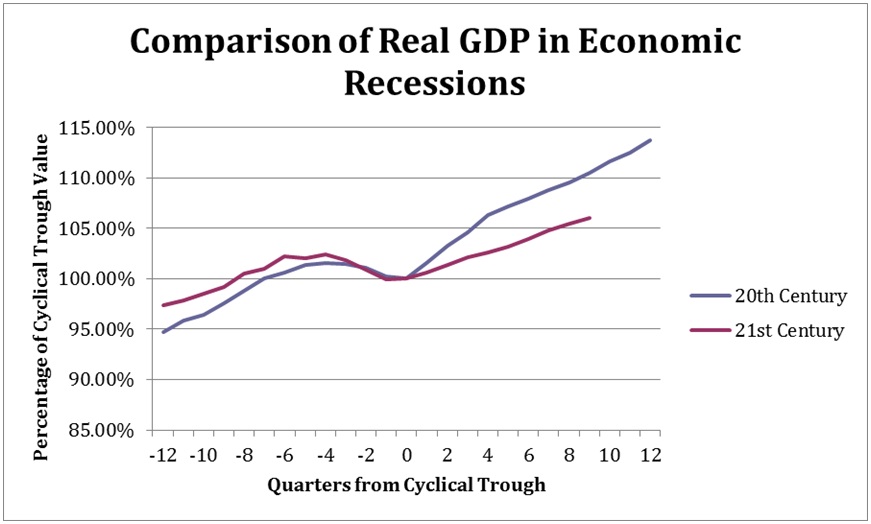

However, the recession-recovery perform in the 21st century suggest that there is a large mismatch between the character of the two most recent recessions and the arsenal of so-called “stimulus” policies that have been deployed to fight them. Beginning with the propitiously timed Bush tax cuts of 2001, discretionary fiscal policies were unleashed in 2002, 2003, 2005, 2008, and most dramatically with the Obama stimulus bill of 2009. As is evident from the chart below, this Keynesian carpet-bombing of recessionary forces has yielded two of the worst recoveries on record.

Perhaps this should not be surprising. Keynesian policies were developed to counter income-driven, cash-flow recessions. Higher interest rates, a decline in animal spirits, or other shocks cut the spending of households and businesses. The reduced cash flows caused businesses to idle factories and lay off workers that, in turn, further reduced family incomes, spending, and business cash flows. Traditional stimulus policies attempted to fight this downdraft by using federal debt to (literally) borrow temporary cash flow from the future and inject it into households and firms during the recession. Tax rebate checks, enhanced unemployment benefits, and other temporary transfers raised family income, permitted spending to stop declining, and generated cash flow for business. The latter could respond by re-opening the shuttered facilities and re-hiring works. The business model was intact and prosperity restored. Voila!

The key feature of the 2000 and 2008 recessions is their asset market origins. The dot-com bubble of the late 1990s collapsed and yielded the first recession of the 21st century. The U.S. housing bubble – which was the same size as the dot-com bust, but much more heavily leveraged – was part of the triggering of a much larger financial crisis. In both instances, sharp asset market declines were the precipitating causes of the distress of the Main Street economy.

…a new philosophy is needed that recognizes that recessions are the same thing as large-scale restructuring.

When the equity and debt financial instruments backing a company decline in value, they are sending the message that the firm’s operations have become unprofitable and need to be restructured. While a demand-driven recession sends the message to hang on until business picks back up, the asset-market recessions send the message to restructure – permanently shed workers, permanently close and optimize facilities, and permanently re-think the product line. The appearance of temporary, government-delivered cash flows does nothing to change this message.

Instead, a new philosophy is needed that recognizes that recessions are the same thing as large-scale restructuring. Workers need the skills necessary to make the transition from an old (and long gone) job to a better future. And government policies should discard the “targeted, temporary” mantra from the past. In these circumstances no government will know what or whom to target, and the new businesses will best benefit from a permanent, pro-growth policy stance.

What does that mean right now? Discard the Mickey Mouse payroll tax holidays in favor of pro-growth tax reform. Give up on stimulus spending in favor of fundamental entitlement reform that eliminates the debt threat.

The American job machine is not broken. But it has noticeably downshifted and suffering the drag of bad public policy.

Douglas Holtz-Eakin served as Director of the Congressional Budget Office from 2003 to 2005. He currently serves as President of the American Action Forum and most recently was a Commissioner on the Congressionally-chartered Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission.