Will the U.S. resemble Greece?

Will the U.S. resemble Greece?

MAYA MACGUINEAS

Question: Is the United States Greece?

Answer: Of course not, our islands aren’t as pretty and our gyros aren’t as tasty. Nonetheless, a U.S. sovereign debt crisis is not nearly as remote as it was once thought to be, and as a result, a debt default is something that, while not likely, is no longer inconceivable. Without question, if we fail to make policy changes, we will experience some type of fiscal crisis down the road.

At the moment, our borrowing patterns still seem manageable. Our debt is very large, with public debt at $8.5 trillion and total debt at over $13 trillion, and we are on track to add another $10 trillion over the next decade. But, as market concerns focus on Greece – with a leery eye also pointed on nearby Spain and Portugal – the United States seems only to be benefiting from the punitive prices other nations are paying because of their excessive debt, and we are able to continue our own borrowing binge at exceedingly low rates.

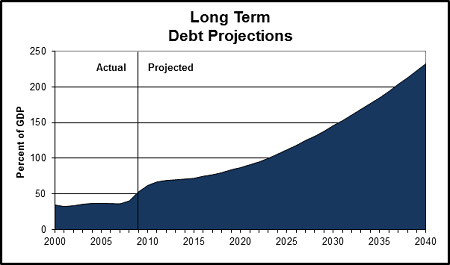

This could turn on a dime. The long-term debt projections are startling. Under reasonable assumptions, the public debt would grow from a historical average of below 40% of GDP to over 60% this year, to around 85% by the end of the decade, to 185% by 2035, and an astronomical 854% by 2080. It makes a college freshman, with his first seven credit cards in one hand and a bottle of Jack Daniel’s in the other, look positively responsible.

And markets are fickle creatures—no money manager wants to be the last mutual, pension, or hedge fund over-weighted in U.S. Treasuries, so while they are happy to park their cash here for now, with the first whiff of U.S. market skittishness, capital will look for other places to go quicker than you can say, but I thought we were the reserve currency? Hello, safe haven anyone?

The U.S. has never directly defaulted before, and a fiscal crisis could play out in a number of ways.

The U.S. has never directly defaulted before, and a fiscal crisis could play out in a number of ways. We could just settle into a damaging but manageable debt cycle where we continue to borrow and creditors continue to lend because there’s nowhere else to put their capital. Government borrowing would squeeze out productive investment, and U.S. growth would remain subpar for years if not decades, but it is the frog in the boiling water scenario, where we would be lulled into complacency and as a result, endure a steady decline in the standard of living compared to where it could have been.

Or, our creditors could start to demand a higher return on their money as they perceived our debt to be more risky. Interest rates would be pushed up, causing interest payments in our budget to grow, forcing us to borrow more, pushing rates up further, leading to a vicious debt spiral. Such a spiral could either be gradual, or abrupt, with both likely pushing the economy back into a recession. This time however, we would not have the fiscal flexibility to respond as we did last time, and the recession would likely be much worse. Or the Fed could be pressured to buy more U.S. debt if lenders didn’t want it, resulting in higher levels of inflation, an erosion in savings, and a nearly impossible inflationary cycle to break. One should study the cases in Latin American countries before concluding inflation is the easy way out of our fiscal problems.

Or things might just get so bad, policymakers would choose the default option. While it seems inconceivable now, borrowing costs could become prohibitively high, and the tax hikes and spending cuts needed to close the gap so draconian that politicians just wouldn’t be willing to make them, and default might look like the best option available. Partisan politics could keep politicians from voting to raise the debt ceiling or policymakers could decide to reorder our debts, limiting what is paid, or lengthening the time over which payments are made. They might even choose to call it something else: a restructuring or renegotiation, or I am sure Frank Luntz could come up with something better.

The standard of living would be in the dumps, with consumption falling off, businesses going belly up, and mass layoffs, making us yearn for the good old days of 10% unemployment.

But regardless of the name, the results would be the same: bad, bad, bad. Burned creditors would stop buying U.S. debt or demand onerous interest premiums heretofore unimaginable in the U.S. Domestic interest rates would skyrocket, causing the economy to sharply contract. The standard of living would be in the dumps, with consumption falling off, businesses going belly up, and mass layoffs, making us yearn for the good old days of 10% unemployment. Governments would be forced to stop doing things that even the staunchest libertarian might miss from sending grandma her check, to feeding and clothing the troops, to augmenting states’ costs for police, fire fighters, and jails. Remember that 1980s TV movie, The Day After, which showed what the country would look like after a nuclear attack? Picture the fiscal version of that.

And the problems wouldn’t end here. To get out of this mess, and we would ultimately have to do what politicians were trying to avoid—raise taxes and cut spending – but to a much greater degree than we ever would have had to if we had acted in advance of a crisis. The direct toll on citizens would be huge as benefits—even for those who rely on them for the most basic necessities—were slashed, and truly burdensome tax rates ate up the incomes and savings of families. There would be no adjustment time as is usually assumed when contemplating large-scale reforms.

To get out of this mess, and we would ultimately have to do what politicians were trying to avoid—raise taxes and cut spending – but to a much greater degree than we ever would have had to if we had acted in advance of a crisis.

But debt does not have to be our destiny. The U.S. can and must change course. No immediate policy actions need to be taken as the economy continues along its shaky recovery—in fact further stimulus (paid for over time so as not to add to the debt) is probably in order.

But we do quickly need to develop and credibly commit to a medium-term fiscal consolidation plan that would bring the debt back down to more manageable levels, as well as a longer plan to control entitlement spending and stabilize the debt so that it doesn’t grow faster than the economy.

The types of policies we should be considering include: thoughtful reductions in defense; a temporary freeze in domestic discretionary spending; raising the retirement age; slowing the growth of Social Security benefits on the upper end; scaling back the amount of subsidies in the new health reform package; asking participants to pay more for their own Medicare; introducing vouchers as part of Medicare (which should work better now that we have created health care exchanges); and, eliminating agriculture subsidies.

On the tax side, (oh yes, there will be a tax side—not a single expert has shown a path to a reasonable and stable debt path through spending cuts alone,) we should start by broadening the tax base by eliminating the employer-provided health care exclusion, which is one of major causes of rising health care costs, and ratcheting down the million-dollar home mortgage interest deduction.

Then we should look to a broad-based carbon tax, which would help to break our energy dependency as well as providing a new revenues stream. Clinging on to unrealistic promises about not raising taxes on anyone, or even just those making less than $250,000, just makes the prospect of a large-scale VAT tax to plug the large fiscal gap down the road all the more likely, rather than more mode rate increases now.

rate increases now.

It may seem like a long list, and it certainly will not be easy, but it is a heck of a lot better than the alternatives. That said, New Zealand real estate—just as a hedge—looks pretty tempting. RF

Maya MacGuineas is the President of the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget and the Director of the Fiscal Policy Program at the New America Foundation.