At one level, the politics and the economics of 2010 appear daunting. Pundits claim that the recent election will only divide government, the two major political parties can’t get along, and government shutdown will be the only real issue discussed.

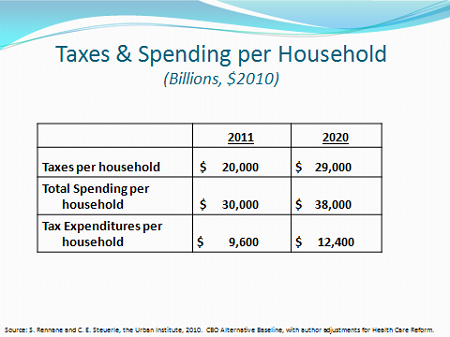

Meanwhile, huge deficits loom. The simple table below tells the story: the federal government spends about $30,000 per household and collects $20,000, and this gap between spending and revenues isn’t expected to decline over the coming decade even with a decent economic recovery.

Those numbers hide an even tougher issue: we’re spending a shrinking share of the budget on children, investment, and mobility-enhancing programs and an ever-increasing share on consumption and programs that discourage work and saving. Even without future deficits, this looks like the ledger sheet of a declining nation.

Quite bluntly, the notion that we can’t tackle these economic and political deficits is hogwash. We tie a straightjacket tighter and tighter around ourselves, and then complain instead of loosening the laces. The really tough problems — unemployment, terrorism, uneducated youth, crime, catastrophic events — still need to be tackled, but at least these aren’t so obviously self-imposed.

The ballooning deficit, though, is. On the spending side, we’re living longer and getting better health care every year. Both are blessings. Trouble is, our politicians promise growth rates in health and retirement programs that are much higher than those at which our personal incomes or taxes can possibly grow.

…our politicians promise growth rates in health and retirement programs that are much higher than those at which our personal incomes or taxes can possibly grow.

In a dream I have, I’m in the Congressional Ways and Means Committee room, which is ornate and exudes history. During a hearing, someone from the National Institutes of Health comes in and shouts, “Eureka, we’ve found the cure! It’s expensive, but it will end cancer!” The audience bursts into applause, imagining longer and better lives for themselves and their children. The members of Congress behind the podium, however, tremble and drip with sweat as they commiserate among themselves. Why, I ask myself in this dream? Then I remember: they foresee a big increase in the cost of Social Security and Medicare and an even deeper deficit.

On the tax side, we’re simply not admitting that we recently cut taxes without reducing spending to pay for the cuts; on the contrary, we went on a spending spree. Combined with the Great Recession stimulus (more tax cuts and spending increases), we pumped our debt up higher and higher — a dark legacy for our kids and theirs. Some of these efforts individually were affordable. Together, they were not.

On top of that, we now provide about $1 trillion in annual subsidies in the tax code. Not all expenditures are bad, of course, whether or not hidden in the tax code. But tax subsidies or “tax expenditures” jack up tax rates higher than they need to be and interfere in the economy exactly like spending programs do. Many tax subsidies have large, built-in growth rates, and few are scrutinized for effectiveness. Meanwhile, dozens of duplicate and overlapping subsidies for children, higher education, capital gains, and so forth make our tax system a bedeviling maze. And we made this mess ourselves.

Throughout November and December 2010, a slew of reports and proposals to deal with long-term budget issues will come due — from the President’s debt commission, and from two private groups: the Bipartisan Policy Center’s commission (headed up by former Senator Pete Domenici and former Congressional Budget Office head Alice Rivlin), and the bipartisan Pew-Peterson Commission on budget policy reform, under the auspices of the Center for a Responsible Federal Budget. The Bipartisan Policy Center is putting forward a specific deficit- reduction plan, while the Peterson-Pew Commission report recommends budget-process reforms that would hold members more accountable and force action when certain danger signals go off. Sure, we’ll all squabble about the proposals these groups make, but these efforts prove that bipartisan efforts are far from impossible. And they will make clear that we can do a lot better than the status quo.

Of course, we need to get the agenda right too. Few disagree that the long-term budget needs fixing, but whether to provide more short-run stimulus is a separate issue. For almost all of the Nation’s history, the long-term budget (had the numbers been crunched) would have shown huge future surpluses under the laws on the books. That’s because most spending was discretionary and scheduled to stay flat or decline. Even Depression and World War II spending didn’t blow the long-term budget since future spending cuts and various tax increases maintained the balance over time if future Congresses were prudent. That’s the main reason past deficits could be reduced without today’s requirement on elected officials to rescind some of the unsustainable growth rates now built directly into programs . Long story short: we can easily afford a short-term stimulus as long as the long-run budget is in balance, but we can’t if it isn’t.

If I were Speaker of the House or the President, I would challenge the other party to join in holding each other accountable in a new budget process based on ideas like those coming out of the Peterson-Pew Commission.

If I were Speaker of the House or the President, I would challenge the other party to join in holding each other accountable in a new budget process based on ideas like those coming out of the Peterson-Pew Commission. I would also take some lessons from Great Britain’s unusual two-party effort to balance the books. (Admittedly, a parliamentary system works differently and there are more than two major parties in Britain, but even two parties seldom agree to accept each other’s proposals and split some differences.) I’d run to prove my party’s leadership by offering to accept a dollar of the other’s long-term budget saving with a dollar of my own, although I would engage neutral referees to deter game playing ( such as proposing saving that is only temporary). Or I’d put some budget-balancing packages from the new commissions on the table and challenge the other party to accept them, rather than the status quo, as the starting point for bargaining. Once on the path of reducing the long-term debt over the next two years, we can then use the next presidential election to determine which type of deficit-reducing action the public favors more.

Then there’s accountability — one item I worked on as a member of the Peterson-Pew Commission. Why shouldn’t the president have to propose and Congress adopt a budget that met certain standards, such as reducing debt relative to the economy? Or being balanced over the economic cycle? In budget presentations by the President’s administration and by congressional budget offices, spending increases should be defined relative to past spending levels, not relative to past promises, many of which were ill considered and just plain unkeepable. (For instance, Medicare is not being “cut” relative to current levels when its growth rate falls from 6 percent to 5 percent!) Congress and the President can also enact triggers that force some deficit reduction when stated economic targets aren’t met.

In the end, long-term deficit reduction or tax simplification or any other initiative alone can’t beat back all the tough issues that face us as a nation. But not acting when there is agreement across the political spectrum that our budget needs an overhaul and we have the means to get started partly explains why Americans are so angry at Washington. The public’s discontent with both political parties reflects the failure of both to get past fighting over the route when almost everyone agrees on the destination: a sustainable and better fiscal future.

Eugene Steuerle is an Institute fellow and the Richard B. Fisher Chair at the nonpartisan Urban Institute. Steuerle is also a former deputy assistant secretary of the Treasury. To subscribe to his free column, visit www.governmentwedeserve.org

Eugene Steuerle is an Institute fellow and the Richard B. Fisher Chair at the nonpartisan Urban Institute. Steuerle is also a former deputy assistant secretary of the Treasury. To subscribe to his free column, visit www.governmentwedeserve.org