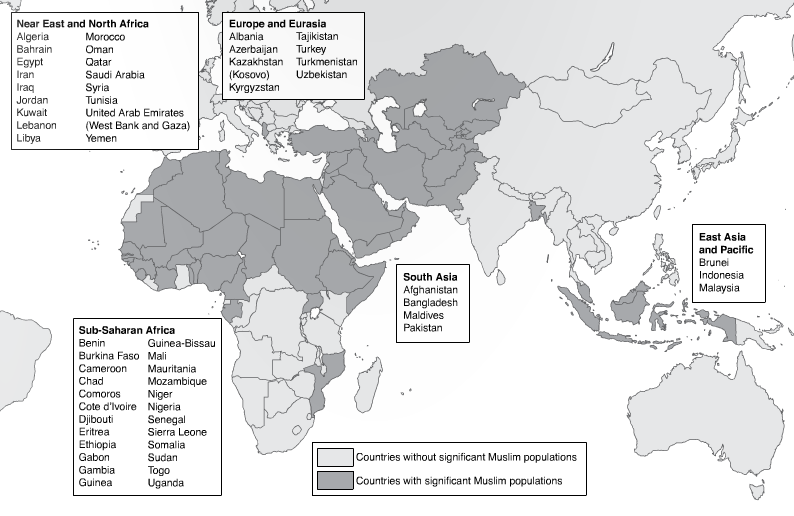

Since Sept. 11, 2001, it has become commplace to say that the United States is engaged in a war of ideas for the hearts and minds of moderate muslims.

Even Donald Rumsfeld has admitted that the metric for measuring success in a war against jihadist terrorism is whether the numbers we kill or deter are greater than the numbers that the jihadists recruit.

We cannot attract the hard core jihadists: they have to be dealt with by hard power. But we cannot win the war unless we win the hearts and minds of the moderates.

The polls suggest that are not doing well.

In key countries like Jordan and Pakistan, more people say they have confidence in Osama bin Laden than in George W. Bush. While some polls show a slight improvement in America’s image in countries like Indonesia and Lebanon, large majorities in the Muslim world remain skeptical about the United States.

We cannot attract the hard core jihadists: they have to be dealt with by hard power. But we cannot win the war unless we win the hearts and minds of the moderates.

Karen Hughes, the Undersecretary of State for Public Diplomacy, has a daunting task. The United States spends only a little over a billion dollars a year on public diplomacy to get our message out, about the same as Britain or France though we are five times larger. We spend nearly 500 times more than that on our hard military power.

The U.S. Information Agency (USIA) was abolished during the Clinton Administration. Proponents argued that giving its functions to an undersecretary in the State Department would integrate them more closely with overall diplomacy. But this change neglected the low value attributed to public diplomacy in the traditional culture of the State Department. The job Hughes now occupies was left vacant for nearly half of the four years of the first Bush Administration. The priorities in Bush’s first term were on America’s hard power, not its soft or attractive power.

President Bush began to pay more attention to soft power in his second term. In addition to rhetoric about promoting democracy and freedom, he made a modest increase in funding for public diplomacy, including both international broadcasting and the State Department’s educational and cultural exchange programs. In the president’s words, “rarely has the need for a sustained effort to ensure foreign understanding for our country and society been so clearly evident.” But even with these increases there is a long way to go.

The U.S. started new broadcasting outlets like Radio Sawa and Al Hurra television for the Arab world, but the latter is widely mistrusted as American propaganda. In any event, better broadcasting is not enough. As U.S. Ambassador to Russia William Burns has pointed out, public diplomacy must be accompanied by “a wider positive agenda for the region, alongside rebuilding Iraq, achieving the President’s two-state vision for Israelis and Palestinians; and modernizing Arab economies.” Even the best advertising cannot sell if the product is poor.

Government propaganda is rarely convincing. America’s strength lies in our civil society. Even when our policies are unpopular, our ability to be self critical as a free society can earn us grudging praise.

Edward R. Murrow, the noted broadcaster who once headed the USIA, argued that the most effective dimension of public diplomacy is not broadcasting but “the last three feet” of face to face communication. To promote this, Hughes has to work with the private and non-profit sectors. To accomplish our objective of promoting democracy in the region, the U.S. must develop a long-term strategy of cultural and educational exchanges aimed at creating a richer and more open civil society in Middle Eastern countries. We need local people who understand America’s virtues as well as our faults. Visa policies that have cut back on the number of Muslim students in the United States do us more harm than good.

Much of the work of developing an open civil society can be promoted by corporations, foundations, universities and other non-profit organizations, as well as by governments. Companies and foundations can offer technology to help modernize Arab educational systems. American universities can establish more exchange programs for students and faculty. Foundations can support the development of institutions of American studies in Muslim countries, or programs that enhance the professionalism of journalists. Private groups can promote the teaching of the English language, and encourage student exchanges.

Karen Hughes will find that America’s soft power is difficult to wield because the government does not control all the levers. But that may not be a bad thing. Government propaganda is rarely convincing. America’s strength lies in our civil society. Even when our policies are unpopular, our ability to be self critical as a free society can earn us grudging praise.

Our diversity is our strength. Only when we manage to unleash this type of soft power and combine it with our hard power will we be successful in meeting the challenge of jihadist terrorism. Then we will be a “smart power.”

Joseph S. Nye teaches at Harvard University and is the author of Soft Power: The Means to Success in World Politics, and The Power Game: A Washington Novel.

“State’s public diplomacy investment in these 58 countries and territories has increased in recent years. According to department data, State provided funds for 179 speakers to travel to these countries in fiscal year 2005, up from 157 in fiscal year 2004. Additionally, the department funded nearly 5,800 exchange participants from these countries in fiscal year 2005, up from 5,100 in fiscal year 2004. The department spent nearly $115 million on exchange and information programs in these countries in fiscal year 2005.” Source: GAO report on Public Diplomacy, May 2006