Vice President Richard Cheney caused a real stir in Vilnius in May when he delivered a major speech on the former communist world.

In blunt language typical for the Vice President, he stated, “in Russia today, opponents of reform are seeking to reverse the gains of the last decade. In many areas of civil society – from religion and the news media, to advocacy groups and political parties – the government has unfairly and improperly restricted the rights of the people. Other actions by the Russian government have been counterproductive, and could begin to affect relations with other countries. No legitimate interest is served when oil and gas become tools of intimidation or blackmail, either by supply manipulation or attempts to monopolize transportation. And no one can justify actions that undermine the territorial integrity of a neighbor, or interfere with democratic movements.”

Russian President Vladimir Putin and his supporters were “outraged.” A Kremlin spokesperson denounced the speech as “inconceivable” and “subjective” in its interpretations of Russian internal affairs. Others in Moscow, as well as some in the West, called the speech a return to the Cold War. One Moscow headline suggested that U.S.-Russian relations were at their lowest level in the last 20 years.

Cheney’s speech and the reaction to it in Moscow do not mark a restart of the Cold War, but U.S.-Russia relations are changing from the dynamics that shaped them for the past two decades. Understanding the difference between the two – that is, between a return to the Cold War and a recognition that the bilateral relationship has changed fundamentally since the more optimistic period of the 1990s – will be crucial to developing a realistic relationship between Russia and the United States in the coming years.

First, let’s be clear: the current interaction between the United States and Russia looks nothing like the Cold War. The Cold War, after all, was a battle between two global superpowers espousing two antithetical ideologies. Millions of people — Russians, Americans, Ukrainians, Koreans, Hungarians, Vietnamese, Czechoslovaks, Angolans, Afghans, and many others – lost their lives in this so-called “cold” war, while the Soviet Union and the United States threatened each other with nuclear annihilation as a strategy to keep the peace. This situation is not returning. Those who invoke the Cold War as a historical analogy for today’s tensions either are ignorant of what really happened during the Cold War or are nostalgic for an era when Russia was considered a superpower.

Russia today does not posses the military or economic capacity to be a second superpower again (and the idea of an “energy superpower” is a bizarre one, since every other major exporter of raw materials in history was on the periphery of the world economy, not in its core). Nor, despite all the recent worry about Russia’s efforts to stop “colored” revolutions, does the Kremlin have a model of governance or ideology that is in demand abroad. For American strategic thinkers, therefore, other rising powers such as China, other ideologies such as Osama bin Ladenism, and other foreign policy concerns such as Iraq, occupy their attention, leaving little time to think about rekindling an antagonistic relationship with Russia. Those who worry about a return to the Cold War have an inflated sense of Russia’s importance to American foreign policy. What Cheney’s speech does signal is that the Bush administration is scaling back its expectations about Russia as a strategic partner for the simple fact that the United States traditionally has more strained and limited relationships with autocracies than it does with democracies. It is this relationship between Russian internal developments and American foreign policy that must be understood.

Since the latter part of the 1980s, Western leaders, including presidents George H.W. Bush, Bill Clinton, and George W. Bush, believed that first the Soviet Union and then Russia was “in transit” from communism to democracy. To help this process of democratization move forward, Western leaders believed that Russia should be integrated into Western institutions. Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev and Russian president Boris Yeltsin believed that they were pushing their countries towards democracy internally and towards integration with the West externally. Putin, however, has reversed these trends.

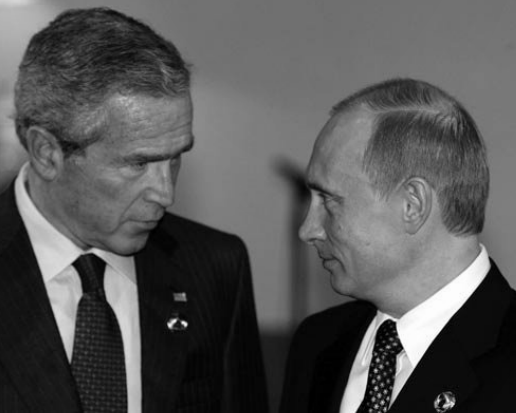

He obviously is not seeking to deepen democracy. Nor, however, is Putin pushing for integration in the West, in part because of frustration with the limited results of this foreign policy and in part because Putin now believes that a revived, more powerful Russia today does not need membership into Western clubs to be a great and “sovereign” international player. It took Washington some time to recognize Putin’s agenda at home and the end of the integration project in foreign relations. Now understood, it is only natural that relations should be based on a different set of expectations.

The United States can do business with autocratic regimes. Since the creation of the United States, American leaders have cooperated with autocracies, such as the French monarchy during the American War of Independence, when it was considered to be in the national interest. But this cooperation always comes with some unease. Relations with democracies are always deeper and more enduring. As Russia has become more autocratic, the strains in bilateral relations were therefore predictable if not inevitable. These strains do not represent a return to the Cold War. Rather, they represent a return to how the United States has traditionally, awkwardly, and often hypocritically dealt with autocracies of strategic importance throughout American history – from Stalin’s Soviet Union to Pakistan today.

Without question, Bush and his successor should continue to work with their Russian counterparts on issues of nation and mutual interest… But as long as Russia remains an autocracy, there will be limits to cooperation just as there always has been in American foreign policy, well before and after the Cold War.

American hopes about warmer relations in the 1990s were either a consequence of a more democratic regime inside Russia or a misunderstanding of that regime’s autocratic nature. But whether it is perception or reality that has changed, the result is the same—more friction.

Without question, Bush and his successor should continue to work with their Russian counterparts on issues of national and mutual interest, be it nonproliferation, the expansion of energy supplies, or the fight against terrorism. No one sensible in Washington either inside or outside of the government is calling for a return to containment. But as long as Russia remains an autocracy, there will be limits to cooperation just as there always has been in American foreign policy, well before and after the Cold War.

If the trajectory inside Russia does change in the future, then Washington and the rest of the West must be ready to reengage more robustly in a strategy for integrating Russia into the Western world, including seemingly radical ideas such as Russian membership in NATO and the European Union. Such ideas can only be entertained after Russia recommits to building a liberal democracy and a genuine market economy. When change does occur, these ideas must be considered seriously, with real interim benchmarks for maintaining the integration trajectory and realistic timetables that will have to stretch decades long.

The first attempt to reintegrate Russia after communism failed. The second chance, whenever it comes, cannot result in failure again.

Michael McFaul is a senior fellow at the Hoover Institution, an associate professor of political science at Stanford University and a Senior Associate at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.