On November 30, 2018, President Donald Trump, Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, and outgoing Mexican President Enrique Peña Nieto signed the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) to replace the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). The new agreement leaves in place the basic framework of NAFTA, but updates the arrangement with revised labor and environmental standards, a new chapter on trade in digital goods, stronger intellectual property protections, and a more stringent set of requirements for automobiles and automotive parts to qualify for tariff-free access in North America.

The first key concept to know about USMCA is that, with its ratification, there will be a North American free trade area. This is a critical point, as the past several years have been filled with uncertainty over whether the United States would withdraw entirely from NAFTA. While USMCA ratification is not guaranteed, the conclusion of trilateral negotiations and the prospects for its implementation are encouraging signs of stability for the region and businesses that operate within it.

Still, the greatest uncertainty for ratification lies with the United States. In Mexico, a simple majority vote in its Senate is required to ratify USMCA. The Mexican president, Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador, reportedly has enough support for the agreement to pass. In Canada, no parliamentary vote is required before the Cabinet ratifies the USMCA, and it is expected that the agreement will be ratified this year. It appears that Mexico and Canada are waiting for signs of US movement towards ratification before concluding their own steps.

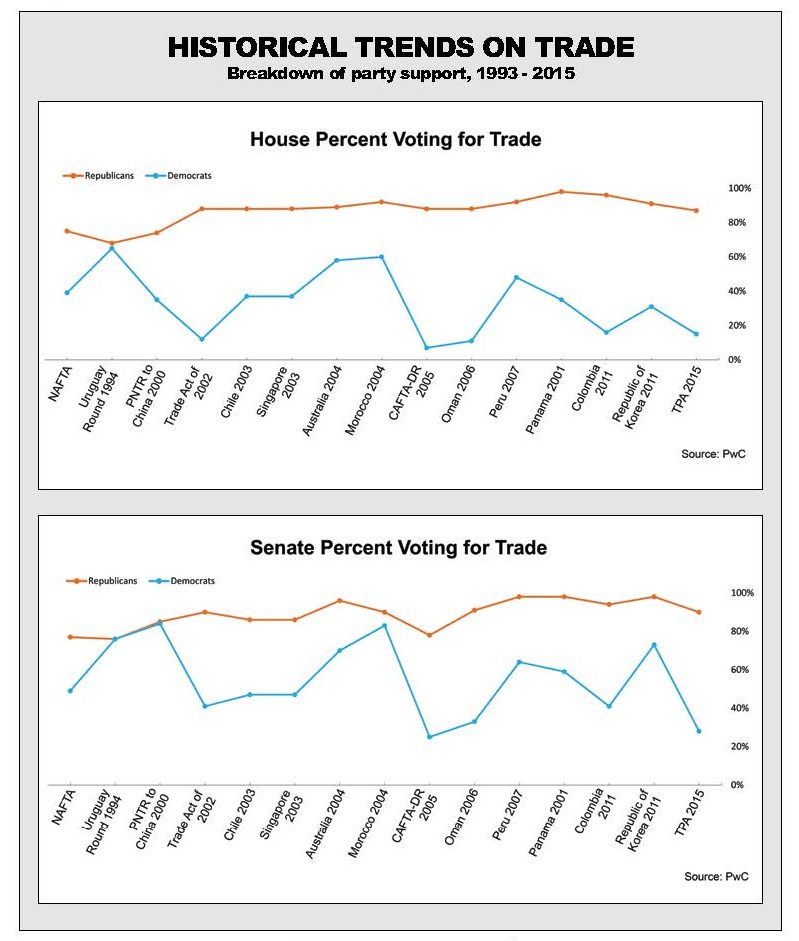

Based on historical trends, there could be enough votes to pass USMCA, but it is not guaranteed.

In the United States, trade promotion authority (TPA), also known as ‘fast track’ trade negotiating authority, sets out a timeline for US ratification of USMCA. The first step of this process has been completed, with the Office of the US Trade Representative (USTR) on January 29 submitting a list of the changes to US law that would be required to bring the United States into compliance with USMCA. The next step requires the International Trade Commission (ITC) to issue to Congress a report assessing the agreement. This report was delayed by the government shutdown earlier this year and now is expected to be delivered to Congress in April.

Next under the TPA timeline, the President will submit a draft statement of administrative action and a copy of the legal text of agreement to Congress at least 30 days before submitting a bill implementing the agreement to Congress for consideration. Lastly, before the implementing bill is introduced in the House and Senate, the President submits a copy of the final legal text of the agreement along with an environmental review, an employment impact review, a report on labor rights, and a plan for implementing and enforcing the agreement. United States Trade Representative Robert Lighthizer has indicated that these steps could be taken this spring, setting up initial USMCA consideration in Congress over the summer.

The TPA process is detailed and deliberative, but it also provides certain advantages to trade legislation. Namely, TPA-compliant trade bills generally are not subject to amendment but rather receive only an up-or-down vote. The no-amendment policy is based on the idea that US trading partners would be unlikely to negotiate if any deal they strike would be subject to later changes by 535 Members of Congress. TPA is all but essential for trade deals – only one such agreement, a trade pact between the United States and Jordan, has been ratified without TPA protections.

However, because the USMCA bill itself is largely unalterable, it is often the case that other legislation ancillary to the USMCA itself may be required to ensure passage. That is, expect some deal-making to occur in order to win support for the pact. Congressional approval of USMCA implementing legislation will require bipartisan agreement between the House and Senate. House and Senate Democrats are expected to focus on labor-related concerns, focusing on the impact of trade on US workers and the ability of the trade partners to enforce their own labor provisions. Domestically, labor unions’ neutrality or support regarding USMCA will be vital for eventual passage in Congress.

Historical data on House and Senate voting percentages for trade issues in the past few decades highlights the challenges of passing trade agreements in Congress (see above chart). Based on historical trends, there could be enough votes to pass USMCA. But it is not guaranteed. Democrats in both the House and the Senate have lower voting percentages in support of trade agreements than Republicans. It will be a point of interest to see if and how this historical dynamic changes with a Democrat-controlled House.

Democrats in both the House and the Senate have lower voting percentages in support of trade agreements than Republicans.

Another complicating factor is the possibility that President Trump will declare United States withdrawal from NAFTA. If he withdraws, it will put pressure Congress to pass USMCA or be left with no trilateral North American trade agreement. Under NAFTA, a notice of withdrawal does not become effective for six months, essentially establishing a deadline for Congress to ratify the new agreement without a lapse, provided the President’s authority in this area is not tested or is sustained. While it is possible that the President may be threatening to use authority he may not have, a presidential notification of NAFTA withdrawal would mean greater uncertainty for business and possibly could result in higher tariffs.

Finally, there is a growing bipartisan call in Congress for President Trump to remove the tariffs on steel and aluminum imports at least as applied to Canada and Mexico before or as part of USMCA ratification. Complicating this issue is the fact that President Trump is considering whether to apply similar tariffs against automobile imports. Further imposition of such tariffs could jeopardize USMCA ratification in Congress.

Despite the many twists and turns ahead, the outlook for ratification later this year remains cautiously optimistic. Politically, USMCA represents an opportunity for both parties to claim an end to NAFTA while at the same time ensuring benefits for North American businesses and consumers alike. Substantively, NAFTA entered into force in 1994, largely before the digital age, and many of the USMCA’s proposed changes are overdue and welcome. USMCA ratification could be the biggest political and legislative development of 2019.

Scott McCandless is a Principal with PricewaterhouseCoopers LLP based in Washington, DC. Scott has over 20 years of private practice as well as government policy experience, including serving as Tax Counsel to US Senator Olympia Snowe; Tax Counsel to Congressman Tim Griffin; and Law Clerk to Judge R. Kenton Musgrave of the US Court of International Trade.

Caitlin MacKay is a Senior Associate in the PricewaterhouseCoopers LLP Tax Policy Services practice in Washington, DC, where she analyzes and provides advice to clients on a wide range of tax and trade policy matters.