Two of the most important questions now being debated in the U.S. are the effects of globalization and immigration on the nation’s economy.

Globalization is accelerating, and it is still not clear whether trends like outsourcing will erode U.S. competitiveness or provide long-term benefits. The focus of the immigration debate is on the plight of millions of unskilled immigrants who have entered the U.S. illegally. Forgotten in this debate are the hundreds of thousands of skilled immigrants that enter the country legally.

A new study shows these skilled immigrants provide the U.S. a greater global edge. They contribute to the economy, create jobs, and lead innovation. Immigrants are fueling the creation of hi-tech business across our nation and creating a wealth of intellectual property.

The study also raises a concern – an increasing percentage of our international patents are being filed by foreign nationals who may not be here to stay.

Immigrants are fueling the creation of hi-tech business across our nation and creating a wealth of intellectual property.

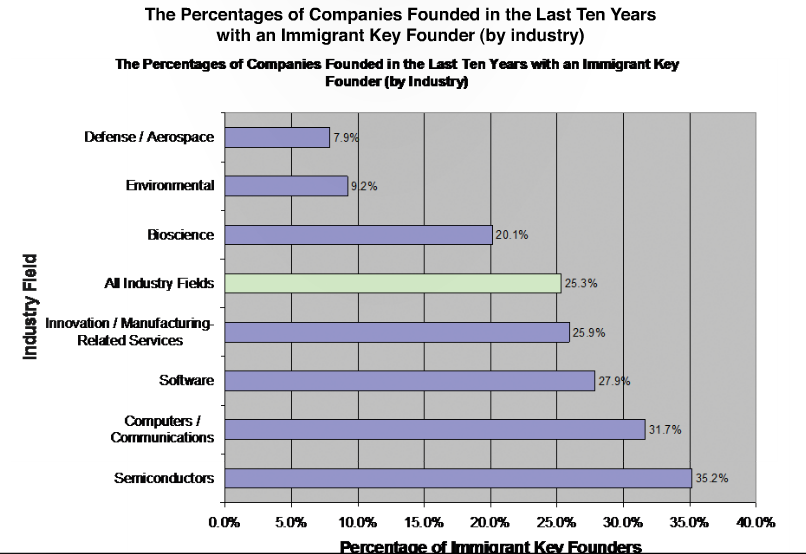

The research conducted by my students at Duke University in collaboration with Dean AnnaLee Saxenian of the University of California, Berkeley was titled, “America’s New Immigrant Entrepreneurs.” We interviewed 2,054 engineering and technology companies started in the U.S. between 1995 and 2005. Here is what we found:

- In 25.3% of these companies, at least one key founder was foreign-born.

- Nationwide, these immigrant founded companies produced $52 billion in sales and employed 450,000 workers in 2005.

- Indians have founded more engineering and technology companies in the U.S. in the past decade than immigrants from Britain, China, Taiwan, and Japan combined. Of all immigrant founded companies, 26% have Indian founders.

- The mix of immigrants varies by state. Hispanics constitute the dominant group in Florida, Israelis constitute the largest founding group in Massachusetts, and Indians dominate New Jersey, with 47% of all immigrant founded startups.

- Almost 80% of immigrant founded companies in the U.S. were within just two industry fields – software and innovation/manufacturing-related services. Immigrants were least likely to start companies in the defense/aerospace and environmental industries.

We also analyzed the patents filed by U.S. residents in the World Intellectual Property Organization patent databases. These are patents that give us a global edge. We found that foreign nationals residing in the U.S. were named as inventors or co-inventors in 24.2% of international patent applications filed from the U.S. in 2006. In 1998, by contrast, this number stood at only 7.3%. To put these numbers into perspective, it is worth noting that Indians and Chinese both constitute less than one percent of the U.S. population, and census data show that 81.8% of Indian immigrants arrived in the U.S. after 1980.

These immigrants come to the U.S. with a good understanding of their home markets and have fresh perspectives. Given that we are going to be increasingly competing with the countries they immigrate from, their knowledge of the global landscape is an asset. Bringing in more skilled immigrants will likely lead to greater economic growth and create a greater intellectual property and competitive advantage. The question is how do we get them here to stay?

Proponents of a temporary visa category called the H1B argue that we should greatly expand the numbers of such visas. They say these visas provide a steady flow of highly skilled professionals who are in short supply, and reduce the need for them to move their operations abroad. Opponents argue that these visas are often misused to bring in workers that don’t have exceptional skills, and that this can impact wages and hurt the engineering profession itself.

Both sides are correct. My view is that if we do need workers with special skills, we should offer them permanent residence rather than short-term visas. Temporary workers can’t start businesses, and don’t have the incentive to help us compete globally or to integrate into American society. They can’t sink deep roots because their visas limit how long they can stay.

The patent data reveals another issue – the percentage of foreign nationals contributing to U.S. international patent applications increased 331% in eight years. This is a welcome contribution to U.S. intellectual property, but many of the engineers and scientists filing these patents may have to return home – taking their knowledge and experience with them. The increasing numbers of patent filings by foreigners correspond to the increasing numbers of foreign graduate and post-graduate students and skilled temporary workers that come to the U.S.

The current backlog for skilled immigrants from India and China in the third preference category (under which they would get permanent residence) stands at nearly six years. In other words, the Immigration and Naturalization Service is currently processing applications for those who applied for permanent residence in 2001. Additionally, there is a yearly limit of 140,000 employment-based visas, with a maximum of 7% being allocated to immigrants from any one country. We have tight limits on how many skilled immigrants can come here and only allow the same numbers from India as from Poland and Senegal.

So, after educating the world’s best and brightest and providing them with extensive experience in American business, we are now setting the stage to force them to return to their home countries – where they could become our competitors.

What we need to do is to open the doors wider for the skilled immigrants we need. Let’s try to keep the brightest students who complete their graduate studies in our universities by making them eligible for green cards. Let’s expand the numbers of skilled immigrants we admit, remove the arbitrary country limits and make it easier for those that contribute to our economy and competitiveness to stay.

After all, we want these people on our side. RF

Vivek Wadhwa is a skilled Indian immigrant who moved to the U.S. in 1980. The founder of two software companies, he is presently an Executive in Residence at Duke University. A complete copy of the Duke University study he coauthored can be found here.