In political and other organizations, long-term success is driven by a culture of ideas for improvement.

In politics, the ideas need to be not only about how to get elected, but also about better ways to serve citizens, organize and manage government, and improve public welfare. In profit-making organizations, the ideas should be about new products to offer customers, or new ways to manage organizations and should be more efficient and effective.

If an organization isn’t talking about both sets of ideas, it isn’t likely to be successful for long.

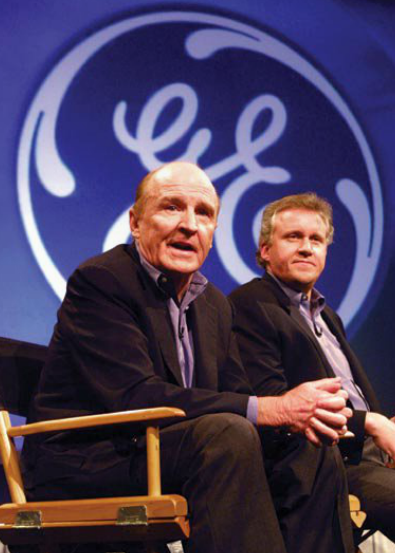

Westinghouse and GE: A Study in Contrasts

Take, for example, Westinghouse and General Electric, two firms that once had many things in common.

Westinghouse Corporation was, at least in its early years, an innovative firm, particularly with regard to the products it offered to the marketplace. The company brought to market the electric power plant, air brakes, the shock absorber, nuclear power, commercial radio, radar, frost-free refrigerators, and many other less dramatic innovations.

More recently, however, it was less innovative in terms of new products, and not innovative at all in terms of how to manage its business. By the early 1980s, financial results and market share (the corporate equivalent of votes and polling data) had become the overriding focus of its executives. Increasing the price of its shares was the only consideration; everything else was expendable.

General Electric, Westinghouse’s competitor since the late 19th century, has also been innovative in terms of products. However, what makes GE truly distinctive is that new ideas about business and management were avidly pursued and viewed as part of the company’s fabric. Certainly, the company sought financial targets, and it bought and sold many businesses. But its history was one of ideas implemented successfully.

In the 1950s, CEO Ralph Cordiner spoke of “customer focus” and “decentralization as a management philosophy.” Cordiner emphasized “continuous innovation in products, processes, facilities, methods, organization, leadership, and all other aspects of the business.”

GE under Jack Welch in the 1980s and 1990s was a veritable idea machine. He trumpeted the concepts of “Work Out,” “boundarylessness,” “speed, simplicity, and self-confidence,” “Six Sigma,” and “digitization,” among several other ideas. His letter in GE’s annual report became a reliable place to find the management ideas that would reshape GE – and many other firms – over the subsequent months and years. GE’s current CEO, Jeffrey Inmelt, has shifted the focus somewhat toward product innovation, but GE still values managerial innovation far more than most firms.

The result is that GE is currently one of the world’s most valuable corporations. Over the past two decades, the company has delivered more than 20% annual growth to shareholders each year. Fortune magazine named Welch “Manager of the Century,” and ranked GE the “Most Admired Company in America” three years in a row; the Financial Times gave GE the “Most Admired Company in the World” award.

Westinghouse, on the other hand, is effectively dead as a company. Its businesses were dismantled and sold off; only its brand remains on Chinese televisions and British nuclear power plants. Its death came as no surprise, as its financial performance had languished for many years.

Why did GE rise to the top of the industrial heap, while its onetime powerful rival sank into the graveyard? Why did GE’s financial performance shoot off the charts, while Westinghouse’s descended into oblivion?

There are many factors that can explain the disparity in these companies’ fortunes, but one is surely their differential embrace of ideas for business improvement.

Of course, there are factors other than ideas and idea oriented people that account for GE’s success and Westinghouse’s demise.

But the companies’ orientations to ideas were certainly contributors to their respective fates.

Ideas in Government

The U.S. government doesn’t generally develop products, so it must focus on innovations in services, processes, management, and leadership. Unfortunately, over the last decade or so, both Republicans and Democrats in Washington have resembled Westinghouse more than GE.

Indeed, the parties have proven to be extremely innovative when it comes to getting elected; witness the GOP’s use of micro-targeting technology in the 2004 general election and the Democrat’s effective use of blogs last fall. When it comes to proposing new solutions that will make a difference in people’s lives, though, they fall back on ideas such as raising the minimum wage that are well-worn and depressingly familiar.

It doesn’t have to be this way. At various times in our history, political parties have been engines for governmental innovation. In the 1930s, Democrats introduced a wide variety of reforms and new approaches to governance in the New Deal. In the early 1990s, Republicans in Congress combined more than ten innovative policies into the Contract with America. At the same time in the Executive branch, the Clinton Administration established the National Performance Review, with over 1,200 recommendations for improving the efficiency and effectiveness of the federal government.

…what makes GE truly distinctive is the new ideas about business and management were avidly pursued and viewed as part of the company’s fabric.

Innovations also come from government at the state and local level. States, for example, were conceived by the Founding Fathers as “laboratories of innovation.” They have actually played that role well – from Massachusetts’ role as the laboratory for the U.S. Constitution, to the many states that have pioneered e-government. Cities – particularly large ones – can also create innovations that can influence all of government.

Witness New York’s adoption of the “Compstat” approach to crime control that has influenced the way even Federal law enforcement agencies work today, and the many innovations from charter schools that are shaping Federal educational policy.

The Idea Practitioners

Ideas in government at any level, however, need a fertile environment in which to grow. Just as General Electric had leaders who nurtured the creation and application of ideas, political leaders who are strong idea advocates are needed as well.

FDR, Newt Gingrich, Al Gore, and a number of governors and mayors – including Eliot Spitzer and Michael Bloomberg in New York – certainly qualify.

Outside of the U.S., Britain’s Tony Blair and Thailand’s Thaksin Shinawatra (recently deposed not for a paucity of ideas, but largely for ethical shortcomings) are or were idea-focused leaders. They don’t necessarily come up with all the ideas themselves, but they surround themselves with innovative people and institutions.

Institutions, in fact, are key. For corporations, the relevant ones are business schools and consulting firms. For government, there are of course schools of government – the Kennedy School at Harvard occasionally injects some new ideas into the polity – but the major players are think tanks. The Heritage Foundation, for example, played a major role in creating the Contract with America, and the Brookings Institution was instrumental in the National Performance Review.

In addition to innovators from outside, idea-focused government (like idea-focused corporations) needs insiders as well who make it their jobs to find better ways to run their organizations. I call them “idea practitioners.” Over the years I’ve come to know a goodly number of such individuals, but there probably aren’t enough. These are mid-level executives like Chris Hoenig, who helped to introduce Chief Information Officers, solutions to the Y2K problem, and national-level social indicators to the U.S. government in his tenure at the Government Accountability Office. Sam Hunter helps the General Services Administration establish innovative and high-performing government facilities; who else but an idea practitioner could head an “Office of Applied Science” at the agency? Mitzie Wertheim introduced activity-based costing to the Department of Defense. None of these managerial innovations were revolutionary, but each makes government work better.

There is no shortage of challenges for our government. Our national competitiveness is slipping, we’re not faring particularly well in foreign relations, we could do much better at educating our children, and we haven’t solved the human problems of crime or addiction.

It’s time for Democrats and Republicans to devote more attention to innovative ways to solve these problems, and less to simply getting into and staying in office. RF

Thomas H. Davenport is the President’s Distinguished Professor of Information Technology and Management at Babson College in Wellesley, Mass. His most recent book is Competing on Analytics: The New Science of Winning.